Following up from the last post, there is a lot more we need to cover. This was intended to be the post where we talk exclusively about benchmarks and numbers. But, I have unfortunately been perfectly taunted and status-locked, like a monster whose “aggro” was pulled by a tank. The reason, of course, is due to a few folks taking issue with my outright dismissal of the C and C++ APIs (and not showing them in the last post’s teaser benchmarks).

Therefore, this post will be squarely focused on cataloguing the C and C++ APIs in detail, and how to design ourselves away from those mistakes in C.

Part of this post will add to the table from Part 1, talking about why the API is trash (rather than just taking it for granted that industry professionals, hobbyists, and academic experts have already discovered how trash it is). I also unfortunately had to add it to the benchmarks we are doing (which means using it in anger). As a refresher, here’s where the table we created left off, with all of what we discovered (including errata from comments people sent in):

| Feature Set 👇 vs. Library 👉 | ICU | libiconv | simdutf | encoding_rs/encoding_c | ztd.text |

| Handles Legacy Encodings | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Handles UTF Encodings | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | 🤨 | ✅ |

| Bounded and Safe Conversion API | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Assumed Valid Conversion API | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Unbounded Conversion API | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Counting API | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Validation API | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Extensible to (Runtime) User Encodings | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Bulk Conversions | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Single Conversions | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Custom Error Handling | ✅ | 🤨 | 🤨 | ✅ | ✅ |

| Updates Input Range (How Much Read™) | ✅ | ✅ | 🤨 | ✅ | ✅ |

| Updates Output Range (How Much Written™) | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Feature Set 👇 vs. Library 👉 | boost.text | utf8cpp | Standard C | Standard C++ | Windows API |

| Handles Legacy Encodings | ❌ | ❌ | 🤨 | 🤨 | ✅ |

| Handles UTF Encodings | ✅ | ✅ | 🤨 | 🤨 | ✅ |

| Bounded and Safe Conversion API | ❌ | ❌ | 🤨 | ✅ | ✅ |

| Assumed Valid Conversion API | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Unbounded Conversion API | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Counting API | ❌ | 🤨 | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Validation API | ❌ | 🤨 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Extensible to (Runtime) User Encodings | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Bulk Conversions | ✅ | ✅ | 🤨 | 🤨 | ✅ |

| Single Conversions | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Custom Error Handling | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Updates Input Range (How Much Read™) | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Updates Output Range (How Much Written™) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

In this article, what we’re going to be doing is sizing up particularly the standard C and C++ interfaces, benchmarking all of the APIs in the table, and discussing in particular the various quirks and tradeoffs that come with doing things in this manner. We will also be showing off the C-based API that we have spent all this time leading up to, its own tradeoffs, and if it can tick all of the boxes like ztd.text does. The name of the C API is going to be cuneicode, a portmanteau of Cuneiform (one of the first writing systems) and Unicode (of Unicode Consortium fame).

| Feature Set 👇 vs. Library 👉 | Standard C | Standard C++ | ztd.text | ztd.cuneicode |

| Handles Legacy Encodings | 🤨 | 🤨 | ✅ | ❓ |

| Handles UTF Encodings | 🤨 | 🤨 | ✅ | ❓ |

| Bounded and Safe Conversion API | 🤨 | ✅ | ✅ | ❓ |

| Assumed Valid Conversion API | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❓ |

| Unbounded Conversion API | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❓ |

| Counting API | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❓ |

| Validation API | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❓ |

| Extensible to (Runtime) User Encodings | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ❓ |

| Bulk Conversions | 🤨 | ✅ | ✅ | ❓ |

| Single Conversions | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❓ |

| Custom Error Handling | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❓ |

| Updates Input Range (How Much Read™) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❓ |

| Updates Output Range (How Much Written™) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❓ |

First, we are going to thoroughly review why the C API is a failure API, and all the ways it precipitates the failures of the encoding conversions it was meant to cover (including the existing-at-the-time Big5-HKSCS case that it does not support).

Then, we will discuss the C++-specific APIs that exist outside of the C standard. This will include going beneath std::wstring_convert’s deprecated API, to find that powers the string conversions that it used to provide. In particular, we will discuss std::codecvt<ExternCharType, InternCharType, StateObject> and the various derived classes std::codecvt(_utf8/_utf16/_utf8_utf16). We will also talk about how the C API’s most pertinent failure leaks into the C++ API, and how that pitfall is the primary reason why Windows, specific IBM platforms, lots of BSD platforms, and more cannot properly support UTF-16 or UTF-32 in its core C or C++ standard library offerings.

Finally, we will discuss ztd.cuneicode / cuneicode, a C library for doing encoding conversions that does not make exceedingly poor decisions in its interfaces.

Standard C

Standard C’s primary deficiency is its constant clinging to and dependency upon the “multibyte” encoding and the “wide character” encoding. In the upcoming C23 draft, these have been clarified to be the Literal Encoding (for "foo" strings, at compile-time (“translation time”)), the Wide Literal Encoding (for L"foo" strings, at compile-time), Execution Encoding (for any const char*/[const char*, size_t] that goes into run time (“execution time”) function calls), and Wide Execution Encoding (for any const wchar_t*/[const wchar_t*, size_t] that goes into run time function calls). In particular, C relies on the Execution Encoding in order to go-between UTF-8, UTF-16, UTF-32 or Wide Execution encodings. This is clear from the functions present in both the <wchar.h> headers and the <uchar.h> headers:

// From Execution Encoding to Unicode

size_t mbrtoc32(char32_t* restrict pc32, const char* restrict s,

size_t n, mbstate_t* restrict ps );

size_t mbrtoc16(char16_t* restrict pc16, const char* restrict s,

size_t n, mbstate_t* restrict ps );

size_t mbrtoc8(char8_t* restrict pc8, const char* restrict s,

size_t n, mbstate_t* restrict ps ); // ⬅ C23 addition

// To Execution Encoding from Unicode

size_t c32rtomb(char* restrict s, char32_t c32,

mbstate_t* restrict ps);

size_t c16rtomb(char* restrict s, char16_t c16,

mbstate_t* restrict ps);

size_t c8rtomb(char* restrict s, char8_t c8,

mbstate_t* restrict ps); // ⬅ C23 addition

// From Execution Encoding to Wide Execution Encoding

size_t mbrtowc(wchar_t* restrict pwc, const char* restrict s,

size_t n, mbstate_t* restrict ps);

// Bulk form of above

size_t mbsrtowcs(wchar_t* restrict dst, const char** restrict src,

size_t len, mbstate_t* restrict ps);

// From Wide Execution Encoding to Execution Encoding

size_t wcrtomb(char* restrict s, wchar_t wc,

mbstate_t* restrict ps);

// Bulk form of above

size_t wcsrtombs(char* restrict dst, const wchar_t** restrict src,

size_t len, mbstate_t* restrict ps);

The naming pattern is “(prefix)(s?)(r)to(suffix)(s?)”, where s means “string” (bulk processing), r” means “restartable” (takes a state parameter so it a string can be re-processed by itself), and the core to which is just to signify that it goes to the prefix-identified encoding to the suffix-identified encoding. mb means “multibyte”, wc means “wide character”, and c8/16/32 are “UTF-8/16/32”, respectively.

Those are the only functions available, and with it comes an enormous dirge of problems that go beyond the basic API design nitpicking of libraries like simdutf or encoding_rs/encoding_c. First and foremost, it does not include all the possible pairings of encodings that it already acknowledges it knows about. Secondly, it does not include full bulk transformations (except in the case of going between execution encoding and wide execution encoding). All in all, it’s an exceedingly disappointing offering, as shown by the tables below.

For “Single Conversions”, what’s provided by the C Standard is as follows:

| mb | wc | c8 | c16 | c32 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mb | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| wc | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| c8 | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| c16 | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| c32 | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

For “Bulk Conversions”, what’s provided by the C Standard is as follows:

| mbs | wcs | c8s | c16s | c32s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mbs | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| wcs | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| c8s | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| c16s | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| c32s | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

As with the other table, the “✅” is for that conversion sequence being supported, and the “❌” is for no support. As you can see from all the “❌” in the above table, we have effectively missed out on a ton of functionality needed to go to and from Unicode encodings. C only provides bulk conversion functions for the “mbs”/”wcs” series of functions, meaning you can kiss any SIMD or other bulk-processing optimizations goodbye for just about every other kind of conversion in C’s API, including any UTF-8/16/32 conversions. Also note that C23 and C++20/23 had additional burdens to fix:

u""andU""string literals did not have to be UTF-16 or UTF-32 encoded;c16andc32did not have to actually mean UTF-16 or UTF-32 for the execution encoding;- the C and C++ Committee believed that

mbcould be used as the “UTF-8” through the locale, which is why they leftc8rtombandmbrtoc8out of the picture entirely until it was fixed up in C23 by Tom Honermann.

These are no longer problems thanks to C++’s Study Group 16, with papers from R.M. Fernandes, Tom Honermann, and myself. If you’ve read my previous blog posts, I went into detail about how the C and C++ implementations could simply define the standard macros __STDC_UTF_32__ and __STDC_UTF_16__ to 0. That is, an implementation could give you a big fat middle finger with respect to what encoding was being used by the mbrtoc16/32 functions, and also not tell you what is in the u"foo" and U"foo" string literals.

This was an allowance that we worked hard to nuke out of existence. It was imperative that we did not allow yet another escalation of char16_t/char32_t and friends ending up in the same horrible situation as wchar_t where it’s entirely platform (and possibly run time) dependent what encoding is used for those functions. As mentioned in the previously-linked blog post talking about C23 improvements, we were lucky that nobody was doing the “wrong” thing with it and always provided UTF-32 and UTF-16. This made it easy to hammer the behavior in all current and future revisions of C and C++. This, of course, does not answer why wchar_t is actually something to fear, and why we didn’t want char16_t and char32_t to become either of those.

So let’s talk about why wchar_t is literally The Devil.

C and wchar_t

This is a clause that currently haunts C, and is — hopefully — on its way out the door for the C++ Standard in C++23 or C++26. But, the wording in the C Standard is pretty straight forward (emphasis mine):

wide character

value representable by an object of type

wchar_t, capable of representing any character in the current locale— §3.7.3 Definitions, “wide character”, N3054

This one definition means that if you have an input into mbrtowc that needs to output more than one (1) wchar_t for the desired output, there is no appreciable way to describe that in the standard C API. This is because there is no reserved return code for mbrtowc to describe needing to serialize a second wchar_t into the wchar_t* restrict pwc. Furthermore, despite being a pointer type, pwc expects only a single wchar_t to be output into it. Changing the definition in future standards to allow for 2 or more wchar_t’s to be written to pwc is a recipe for overwriting the stack for code that updates its standard library but does not re-compile the application to use a larger output buffer. Taking this kind of action would ultimately end up breaking applications in horrific ways (A.K.A, an ABI Break), so it is fundamentally unfixable in Standard C.

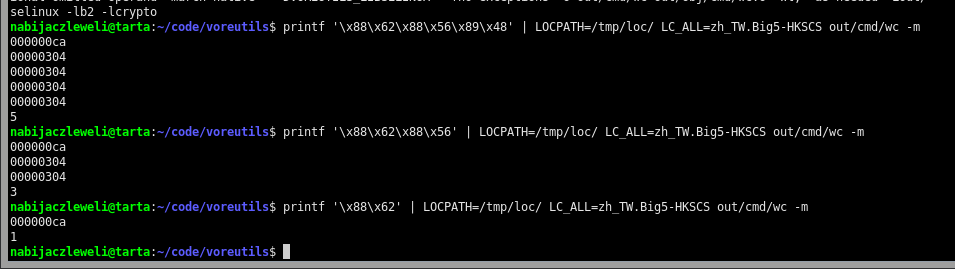

This is why encodings like Big5-HKSCS cannot be used in Standard C. Despite libraries advertising support for them like glibc and its associated locale machinery, they return non-standard and unexpected values to cope with inputs that need to write out two UTF-32 code points for a single indivisible unit of input. Most applications absolutely cannot cope with these return values, and so they start just outputting straight up garbage values as they don’t know how to bank up the characters and perform reads anymore, let alone do writes. It’s doubly-fun when others get to see it in real-time, too:

oh wow, even better: glibc goes absolutely fucking apeshit (returns

0for eachmbrtowc()after the initial one that eats 2 bytes; hereinwcmodified to write the resulting character)

This same reasoning applies to distributions that attempt to use UTF-16 as their wchar_t encoding. Similar to how Big5-HKSCS requires two (2) UTF-32 code points for some inputs, large swaths of the UTF-16 encoded characters use a double code unit sequence. Despite platforms like e.g. Microsoft Windows having the demonstrated ability to produce wchar_t strings that are UTF-16 based, the standard library must explicitly be an encoding that is called “UCS-2”. If a string is input that requires 2 UTF-16 code units — a leading surrogate code unit and its trailing counterpart surrogate code unit — there is no expressible way to do this in C. All that happens is that, even if they recognize an input sequence that generates 2 UTF-16 wchar_t code units, it will get chopped in half and the library reports “yep, all good”. Microsoft is far from the only company in this boat: IBM cannot fix many of their machines, same as Oracle and a slew of others that are ABI-locked into UTF-16 because they tried to adopt Unicode 1.0 faster than everyone else and got screwed over by the Unicode Consortium’s crappy UCS-2 version 1.0 design.

This, of course, does not even address that wchar_t on specific platforms does not have to be either UTF-16 or UTF-32, and thanks to some weasel-wording in the C Standard it can be impossible to detect if even your string literals are appropriately UTF-32, let alone UTF-16. Specifically, the predefined macro __STDC_ISO_10646__ can actually be turned off by a compiler because, as far as the C Committee is concerned, it is a reflection of a run time property (whether or not mbrtowc can handle UTF-32mor UTF-16, for example), which is decided by locale (yes, wchar_t can depend on locale, like it does on several IBM and *BSD-based machines). Thusly, as __STDC_ISO_10646__ is a reflection of a run time property, it becomes technically impossible to define before-hand, at compile time, in the compiler.

So, the easiest answer — even if your compiler knows it encodes L"foo" strings as 32-bit wchar_t with UTF-32 code points — is to just advertise its value 0. It’s 100% technically correct to do so, and that’s exactly what compilers like Clang do. GCC would be in a similar boat as well, but they cut a backdoor implementation deal with numerous platforms. A header called stdc-predef.h is looked up at the start of compilation and contains a definition determining whether __STDC_ISO_10646__ may be considered UTF-32 for the platform and other such configuration parameters. If so, GCC sets it to 1. Clang doesn’t want to deal with stdc-predef.h, or lock in any of the GCC-specific ways of doing things in this avenue too much, so they just shrug their shoulders and set it to 0.

I could not fix this problem exactly, myself. It was incredibly frustrating, but ultimately I did get something for a few implementations. In coordination with Corentin Jabot’s now-accepted P1885, I provided named macro string literals or numeric identifiers to identify the encoding of a string literal1. This allows a person to identify (at least for GCC, Clang, and (now) MSVC) the encoding they use with some degree of reliability and accuracy. The mechanism through which I implemented this and suggested it is entirely compiler-dependent, so it’s not as if other frontends for C or C++ will do this. I hope they’ll follow through and not continue to leave their users out to dry. For C++26 and beyond, Corentin Jabot’s paper will be enough to solve things on the C++ side. C is still left in the dark, but that’s just how it is all the time anyways these days so it’s not like C developers will be any less sad than when they started.

C and “multibyte” const char* Encodings

As mentioned briefly before, the C and C++ Committee believed that the Execution Encoding could just simply be made to be UTF-8. This was back when people still had faith in locales (an attitude still depressingly available in today’s ecosystem, but in a much more damaging and sinister form to be talked about later). In particular, there are no Unicode conversions except those that go through the opaque, implementation-defined Execution Encoding. For example, if you wanted to go from the Wide Execution Encoding (const wchar_t*) to UTF-8, you cannot simply convert directly from a const wchar_t* wide_str string — whatever encoding it may be — to UTF-8. You have to:

- set up an intermediate

const char temp[MB_MAX_LEN];temporary holder; - call

wcrtomb(temp, *wide_str, …); - feed the data from

tempintombrtoc8(temp, …); - loop over the

wide_strstring until you are out of input; - loop over any leftover intermediate input and write it out; and,

- drain any leftover state-held data by checking

mbsinit(state)(if using ther-based restartable functions).

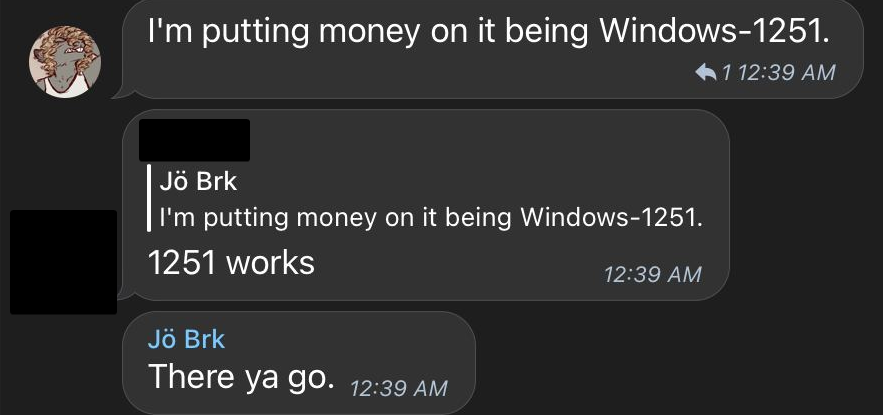

The first and most glaring problem is: what happens if the Execution Encoding is not Unicode? It’s an unfortunately frightfully common case, and as much as the Linux playboys love to shill for their platform and the “everything is UTF-8 by default” perspective, they’re not being honest with you or really anyone else on the globe. For example, on a freshly installed WSL Ubuntu LTS, with sudo apt-get update and sudo apt-get dist-upgrade freshly run, when I write a C or C++ program to query what the locale is with getlocale and compile that program with Clang 15 with as advanced of a glibc/libstdc++ as I can get, this is what the printout reads:

=== Encoding Names ===

Literal Encoding: UTF-8

Wide Literal Encoding: UTF-32

Execution Encoding: ANSI_X3.4-1968

Wide Execution Encoding: UTF-32

If you look up what “ANSI_X3.4-1968” means, you’ll find that it’s the most obnoxious and fancy way to spell a particularly old encoding. That is to say, my default locale when I ask and use it in C or C++ — on my brand new Ubuntu 20.04 Focal LTS server, achieved from just pressing “ok” to all the setup options, installing build essentials, and then going out of my way to get the most advanced Clang I can and combine it with the most up-to-date glibc and libstdc++ I can —

is ASCII.

Not UTF-8. Not Latin-1!

Just ASCII.

Post-locale, “const char* is always UTF-8”, “UTF-8 is the only encoding you’ll need” world, eh? 🙄

Windows fares no better, pulling out the generic default locale associated with my typical location since the computer’s install. This means that if I decide today is a good day to transcode between UTF-16 and UTF-8 the “standard” way, everything that is not ASCII will simply be mangled, errored on, or destroyed. I have to adjust my tests when I’m using code paths that go through standard C or C++ paths, because apparently “Hárold” is too hardcore for Ubuntu 22.04 LTS and glibc to handle. I have long since had to teach not only myself, but others how to escape the non-UTF-8 hell on all kinds of machines. For a Windows example, someone sent me a screenshot of a bit of code whose comments looked very much like it was mojibake’d over Telegram:

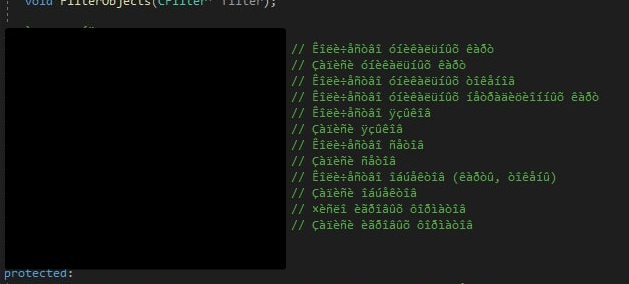

Visual Studio was, of course, doing typical Microsoft-text-editor-based Visual Studio things here. It was clear what went down, so I gave them some advice:

![A screenshot of a telegram conversation. The text is all from a person with a rat avatar, named "Jö Brk": "you're dealing with 1 of 2 encodings." "1 - Windows 1251. Cyrillic [sic] encoding, used in Russia." "2 - UTF-8" "It's treating it as the wrong encoding. Chances are you need to go to "open file as", specifically, and ask it to open as UTF-8." "If that doesn't work, try Windows 1251." "When you're done with either, try re-saving the file as UTF-8, after you find the right encoding." "I'm putting money on it being Windows-1251".](/assets/img/2023/06/telegram-advice.jpg)

And, ‘lo and behold:

Of course, some questions arise. One might be “How did you know it was Windows 1251?”. The answer is that I spent a little bit of time in The Mines™ using alternative locales on my Windows machine — Japanese, Chinese, German, and Russian — and got to experience first-hand how things got pretty messed up by an overwhelming high number of programs. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg: Windows 1251 is the most persistent encoding for Cyrillic data into/out of Central & Eastern Europe, as well as Far North Asia. There’s literally an entire Wiki that contains common text sequences and their Mojibake forms when incorrectly interpreted as other forms of encodings, and most Cyrillic users are so used to being fucked over by computing in general that they memorized the various UTF and locale-based mojibake results, able to read pure mangled text and translate that in-real-time to what it actually means in their head. (I can’t do that: I have to look stuff up.) It’s just absurdly common to be dealing with this:

Me: “Why is the program not working?”

[looks at error logs]

Me: “Aha.”

Even the file name for the above embedded image had to be changed from ólafur-tweet.png to waage-tweet.png, because Ruby — when your Windows and Ruby is not “properly configured” (????) — will encounter that name from Jekyll, then proceed to absolutely both crap and piss the bed about it by trying to use the C standard-based sysopen/rb_sysopen on it. By default, that will use the locale-based file APIs on Windows, rather than utilizing the over 2-decade old W-based Windows APIs to open files. It’s extraordinary that despite some 20+ years of Unicode, almost every programming language, operating system, core library, or similar just straight up does not give a single damn about default Unicode support in any meaningful way! (Thank God at least Python tries to do something and gets pretty far with its myriad of approaches.)

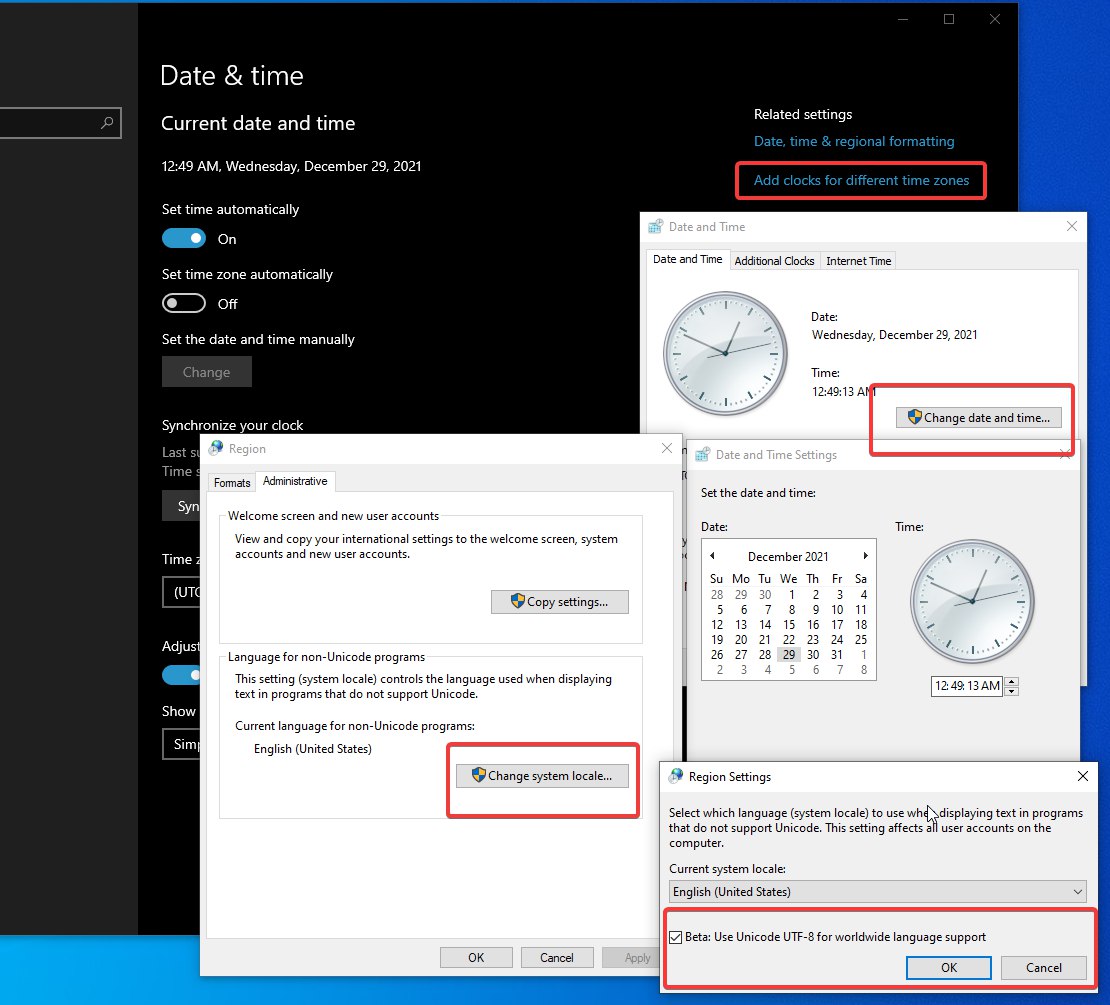

There are other ways to transition your application to UTF-8 on Windows, even if you might receive Windows 1251 data or something else. Some folks achieve it by drilling Application Manifests into their executables. But that only works for applications; ztd.text and ztd.cuneicode are libraries. How the hell am I supposed to Unicode-poison an application that consumes my library? The real answer is that there is still no actual solution, and so I spend my time telling others about this crappy world when C and C++ programs inevitably destroy people’s data. But, there is one Nuclear Option you can deploy as a Windows user, just to get UTF-8 by-default as the default codepage for C and C++ applications:

Yep, the option to turn on UTF-8 by default is buried underneath the new Settings screen, under the “additional clocks” Legacy Settings window on the first tab, into the “Region” Legacy Settings window on the second tab (“Administrative”), and then you need to click the “Change system locale” button, check a box, and reset your computer.

But sure, after you do all of that, you get to live in a post-locale world2. 🙃

And It Gets Worse

Because of course it gets worse. The functions I listed previously all have an r in the middle of their names; this is an indicator that these functions take an mbstate_t* parameter. This means that the state used for the conversion sequence is not taken from its alternative location. The alternative location is, of course, implementation-defined when you are not using the r-styled functions.

This alternative mbstate_t object might be a static storage duration object maintained by the implementation. It may be thread_local, it may not, and whether or not it is thread safe there is still the distinct horribleness that it is an opaquely shared object. So even if the implementation makes it thread-safe and synchronizes access to it (kiss your performance good-bye!), if, at any point, someone uses the non-r versions of the above standard C functions, any subsequent non-r functions downstream of them have their state changed out from underneath them. Somehow, our systems programming language adopted scripting-language style behavior, where everything is connected to everything else is a jumble of hidden and/or global state, grabbing variables and functionality from wherever and just loading it up willy-nilly. This is, of course, dependable and rational behavior that can and will last for a long time and absolutely not cause severe problems down the road. It definitely won’t lead to ranting screeds3 from developers who have to deal with it.

Of course, even using the r functions still leaves the need to go through the multibyte character set. Even if you pass in your own mbstate_t object, you still have to consult with the (global) locale. If at any point someone calls setlocale("fck.U"); you become liable to deal with that change in further downstream function calls. Helpfully, the C standard manifests this as unspecified behavior, even if we are storing our own state in an mbstate_t! If one function call starts in one locale with one associated encoding, but ends up in another locale with a different associated encoding during the next function call, well. Eat shit, I guess! This is because mbstate_t, despite being the “state” parameter, is still beholden to the locale when the function call was made and the mbstate_t object is not meant to store any data about the locale for the function call! Most likely you end up with either hard crashes or strange, undecipherable output even for what was supposed to be a legal input sequences, because the locale has changed in a way that is invisible to both the function call and the shared state between function calls with mbstate_t.

So, even if you try your hardest, use the restartable functions, and track your data meticulously with mbstate_t, libraries in the stack that may set locale will blow up everyone downstream of them, and applications which set locale may end up putting their upstream dependencies in an untested state of flux that they are entirely unprepared for. Of course, nobody sees fit to address this: there’s no reasonable locale_t object that can be passed into any of these functions, no way of removing the shadowy specter of mutable global state from the core underlying functionality of our C libraries. You either use it and deal with getting punched in the face at seemingly random points in time, or you don’t and rewrite large swaths of your standard library distribution.

All in all, just one footgun after another when it comes to using Standard C in any remotely scalable fashion. It is not surprise that the advice for these functions about their use is “DO. NOT.”, which really inspires confidence that this is the base that every serious computation engine in the world builds on for their low-level systems programming. This, of course, leaves only the next contender to consider: standard C++.

Standard C++

When I originally discussed Standard C++, I approached it from its flagship API — std::wstring_convert<…> — and all the problems therein. But, there was a layer beneath that I had filed away as “trash”, but that could still be used to get around many of std::wstring_convert<…>’s glaring issue. For example, wstring_convert::to_bytes always returns a new std::string-alike by-value, meaning that there’s no room to pre-allocate or pre-reserve data (giving it the worst of the allocation penalty and any pessimistic growth sizing as the string is converted). It also always assumes that the “output” type is char-based, while the input type is Elem-based. Coupled with the by-value, allocated return types, it makes it impossible to save on space or time, or make it interoperable with a wide variety of containers (e.g., TArray<…> from Unreal Engine or boost::static_vector), requiring an additional copy to put it into something as simple as a std::vector.

But, it would be unfair to judge the higher-level — if trashy — convenience API when there is a lower-level one present in virtual-based codecvt classes. These are member functions, and so the public-facing API and the protected, derive-ready API are both shown below:

template <typename InternalCharType,

typename ExternalCharType,

typename StateType>

class codecvt {

public:

std::codecvt_base::result out( StateType& state,

const InternalCharType* from,

const InternalCharType* from_end,

const InternalCharType*& from_next,

ExternalCharType* to,

ExternalCharType* to_end,

ExternalCharType*& to_next ) const;

std::codecvt_base::result in( StateType& state,

const ExternalCharType* from,

const ExternalCharType* from_end,

const ExternalCharType*& from_next,

InternalCharType* to,

InternalCharType* to_end,

InternalCharType*& to_next ) const;

// …

protected:

virtual std::codecvt_base::result do_out( StateType& state,

const InternalCharType* from,

const InternalCharType* from_end,

const InternalCharType*& from_next,

ExternalCharType* to,

ExternalCharType* to_end,

ExternalCharType*& to_next ) const;

virtual std::codecvt_base::result do_in( StateType& state,

const ExternalCharType* from,

const ExternalCharType* from_end,

const ExternalCharType*& from_next,

InternalCharType* to,

InternalCharType* to_end,

InternalCharType*& to_next ) const;

// …

}

Now, this template is not supposed to be anything and everything, which is why it additionally has virtual functions on it. And, despite the poorness of the std::wstring_convert<…> APIs, we can immediately see the enormous benefits of the API here, even if it is a little verbose:

- it cares about having both a beginning and an end;

- it contains a third pointer-by-reference (rather than using a double-pointer) to allow someone to know where it stopped in its conversion sequences; and,

- it takes a

StateType, allowing it to work over a wide variety of potential encodings.

This is an impressive and refreshing departure from the usual dreck, as far as the API is concerned. As an early adopter of codecvt and wstring_convert, however, I absolutely suffered its suboptimal API and the poor implementations, from Microsoft missing wchar_t specializations that caused wstring_convert to break until they fixed it, or MinGW’s patched library deciding today was a good day to always swap the bytes of the input string to produce Big Endian data no matter what parameters were used, it was always a slog and a struggle to get the API to do what it was supposed to do.

But the thought was there. You can see how this API could be the one that delivered C++ out of the “this is garbage nonsense” mines. Maybe, it could even be the API for C++ that would bring us all to the promised land over C. They even had classes prepared to do just that, committing to UTF-8, UTF-16, and UTF-32 while C was still struggling to get past “char* is always (sometimes) UTF-8, just use the multibyte encoding for that”:

template <typename Elem,

unsigned long Maxcode = 0x10ffff,

std::codecvt_mode Mode = (std::codecvt_mode)0

> class codecvt_utf8 : public std::codecvt<Elem, char, std::mbstate_t>;

template <typename Elem,

unsigned long Maxcode = 0x10ffff,

std::codecvt_mode Mode = (std::codecvt_mode)0

> class codecvt_utf16 : public std::codecvt<Elem, char, std::mbstate_t>;

template <typename Elem,

unsigned long Maxcode = 0x10ffff,

std::codecvt_mode Mode = (std::codecvt_mode)0

> class codecvt_utf8_utf16 : public std::codecvt<Elem, char, std::mbstate_t>;

UTF-32 is supported by passing in char32_t as the Elem element type. The codecvt API was byte-oriented, meaning it was made for serialization. That meant it would do little-endian or big-endian serialization by default, and you had to pass in std::codecvt_mode::little_endian to get it to behave. Similarly, it sometimes would generate or consume byte order markers if you passed in std::codecvt_mode::consume_header or std::codecvt_mode::generate_header (but it only generates a header for UTF-16 or UTF-8, NOT for UTF-32 since UTF-32 was considered the “internal” character type for these and therefore not on the “serialization” side, which is what the “external” character type was designated for). It was a real shame that the implementations were fairly lackluster when it first came out because this sounds like (almost) everything you could want. By virtue of being a virtual-based interface, you could also add your own encodings to this, which therefore made it both compile-time and run-time extensible. Finally, it also contained error codes that went beyond just “yes the conversion worked” and “no it didn’t lol xd”, with the std::codecvt_base::result enumeration:

enum result {

ok,

partial,

error,

noconv

};

whose values mean:

result::ok— conversion was completed with no error;result::partial— not all source characters were converted;result::error— encountered an invalid character; and,result::noconv— no conversion required, input and output types are the same.

This is almost identical to ztd.text’s ztd::text::encoding_error type, with the caveat that ztd.text also accounts for the “all source characters could be converted, but the write out was partial” while gluing the result::noconv into its version of result::ok instead. This small difference, however, does contribute in one problem. And that one problem does, eventually, fully cripple the API.

The “1:N” and “N:1” Rule

Remember how this interface is tied to the idea of “internal” and “external” characters, and the normal “wide string” versus the internal “byte string”? This is where something sinister leaks into the API, by way of a condition imposed by the C++ standard. Despite managing to free itself from wchar_t issues by way of having an API that could allow for multiple input and multiple outputs, it reintroduces them by applying a new restriction focused exclusively on basic_filebuf-related containers.

A

codecvtfacet that is used bybasic_filebuf([file.streams]) shall have the property that if

do_out(state, from, from_end, from_next, to, to_end, to_next)would return

ok, wherefrom != from_end, then

do_out(state, from, from + 1, from_next, to, to_end, to_next)shall also return

ok, and that if

do_in(state, from, from_end, from_next, to, to_end, to_next)would return

ok, whereto != to_end, then

do_in(state, from, from_end, from_next, to, to + 1, to_next)shall also return

ok.252— Draft C++ Standard, §30.4.2.5.3 [locale.codecvt.virtuals] ¶4

And the footnote reads:

252) Informally, this means that

basic_filebufassumes that the mappings from internal to external characters is 1 to N: that acodecvtfacet that is used bybasic_filebufcan translate characters one internal character at a time.— Draft C++ Standard, §30.4.2.5.3 [locale.codecvt.virtuals] ¶4 Footnote 252

In reality, what this means is that, when dealing with basic_filebuf as the thing sitting on top of the do_in/do_out conversions, you must be able to not only convert 1 element at a time, but also avoid returning partial_conv and just say “hey, chief, everything looks ok to me!”. This means that if someone, say, hands you an incomplete stream from inside the file, you’re supposed to be able to read only 1 byte of a 4-byte UTF-8 character, say “hey, this is a good, complete character — return std::codecvt_mode::ok!!”, and then let the file proceed even if it never provides you any other data.

It’s hard to find a proper reason for why this is allowed. If you are always allowed to feed in exactly 1 internal character, and it is always expected to form a complete “N” external/output characters, then insofar as basic_filebuf is concerned it’s allowed to completely mangle your data. This means that any encoding where it does not produce 1:N data (for example, produces 2:N or really anything with M:N where M ≠ 1) is completely screwed. Were you writing to a file? Well, good luck with that. Network share? Ain’t that a shame! Manage to open a file descriptor for a pipe and it’s wrapped in a basic_filebuf? Sucks to be you! Everything good about the C++ APIs gets flushed right down the toilet, all because they wanted to support the — ostensibly weird-as-hell — requirement that you can read or write things exactly 1 character at a time. Wouldn’t you be surprised that some implementation, somewhere, used exactly one character internally as a buffer? And, if we were required to ask for more than that, it would be an ABI break to fix it? (If this is a surprise to you, you should go back and read this specific section in this post about ABI breaks and how they ruin all of us.)

Of course, they are not really supporting anything, because in order to avoid having to cache the return value from in or out on any derived std::codecvt-derived class, it just means you can be fed a completely bogus stream and it’s just considered… okay. That’s it. Nothing you or anyone else can do about such a situation: you get nothing but suffering on your plate for this one.

An increasingly nonsensical part of how this specification works is that there’s no real way for the std::codecvt class to know that it’s being called up-stream by a std::basic_filebuf, so either every derived std::codecvt object has to be okay with artificial truncation, or the developers of the std::basic_filebuf have to simply throw away error codes they are not interested in and ignore any incomplete / broken sequences. It seems like most standard libraries choose the latter, which results in, effectively, all encoding procedures for all files to be broken in the same way wchar_t is broken in C, but for literally every encoding type if they cannot figure out how to get their derived class or their using class and then figure out if they’re inside a basic_filebuf or not.

Even more bizarrely, because of the failures of the specification, std::codecvt_utf16/std::codecvt_utf8 are, in general, meant to handle UCS-2 and not UTF-164. (UCS-2 is the Unicode Specification v1.0 “wide character” set that handles 65535 code points maximum, which Unicode has already surpassed quite some time ago.) Nevertheless, most (all?) implementations seem to defy the standard, further making the class’s stated purpose in code a lot more worthless. There are also additional quirks that trigger undefined behavior when using this type for text-based or binary-based file writing. For example, under the deprecated <codecvt> description for codecvt_utf16, the standard says in a bullet point

The multibyte sequences may be written only as a binary file. Attempting to write to a text file produces undefined behavior.

Which, I mean. … What? Seriously? My encoding things do not work well with my text file writing, the one place it’s supposed to be super useful in? Come on! At this point, there is simply an enduring horror that leads to a bleak — if not fully disturbed — fascination about the whole situation.

Fumbling the Bag

If it was not for all of these truly whack-a-doodle requirements, we would likely have no problems. But it’s too late: any API that uses virtual functions are calcified for eternity. Their interfaces and guarantees can never be changed, because changing and their dependents means breaking very strong binary guarantees made about usage and expectations. I was truly excited to see std::codecvt’s interface surpassed its menial std::wstring_convert counterpart in ways that actually made it a genuinely forward-thinking API. But. It ultimately ends up going in the trash like every other Standard API out there. So close,

yet so far!

The rest of the API is the usual lack of thought put into an API to optimize for speed cases. No way to pass nullptr as a marker to the to/from_end pointers to say “I genuinely don’t care, write like the wind”, though on certain standard library implementations you could probably just get away with it5. There’s also no way to just pass in nullptr for the entire to_* sets of pointers to say “I just want you to give me the count back”; and indeed, there’s no way to compute such a count with the triple-input-pointer, triple-output-pointer API. This is why the libiconv-style of pointer-to-pointer, pointer-to-size API ends up superior: it’s able to capture all use cases without presenting problematic internal API choices or external user use choices (even if libiconv itself does not live up to its API’s potential).

This is, ostensibly, a part of why the std::wstring_convert performance and class of APIs suck as well. They ultimately cannot perform a pre-count and then perform a reservation, after doing a basic from_next - from check to see if the input is large enough to justify doing a .reserve(…)/.resize() call before looping and push_back/insert-ing into the target string using the .in and .out APIs on std::codecvt. You just have to make an over-estimate on the size and pre-reserve, or don’t do that and just serialize into a temporary buffer before dumping into the output. This is the implementation choice that e.g. MSVC makes, doing some ~16 characters at a time before vomiting them into the target string in a loop until std::codecvt::in/out exhausts all the input. You can imagine that encoding up to 16 characters at-most in a loop for a string several megabytes long is going to be an enormous no-no for many performance use cases, so that tends to get in the way a little bit.

There is, of course, one other bit about the whole C++ API that once again comes to rear its ugly head in our faces.

Old Habits Die Hard

There is also another significant problem with the usage of std::codecvt for its job; it relies on a literal locale object / locale facet to get its job done. Spinning up a std::codecvt can be expensive due to its interaction with std::locale and the necessity of being attached to a locale. It is likely intended that these classes can be used standalone, without attaching it to the locale at all (as their destructors, unlike other locale-based facets) were made public and callable rather than hidden/private. This means they can be declared on the stack and used directly, at least.

This was noticeably bad, back when I was still using std::codecvt and std::wstring_convert myself in sol2. Creating a fresh object to do a conversion resulted in horrible performance characteristics for that convert-to-UTF-8 routine relying on standard library facilities. These days, I have been doing a hand-written, utterly naïve UTF-8 conversions, which has stupidly better performance characteristics simply because it’s not dragging along whatever baggage comes with locales, facets, wstring_convert, codecvt, and all of its ilk. Which is just so deeply and bewilderingly frustrating that I can get a thumbs up from users by just doing the most head-empty, braindead thing imaginable and its just so much better than the default actions that come with the standard library.

Constantly, we are annoyed in the Committee or entirely dismissive of game development programmers (and I am, too!) of many of their concerns. But it is ENTIRELY plausible to see how they can start writing off entire standard libraries when over and over again you can just do the world’s dumbest implementation of something and it kicks the standard library’s ass for inputs small and large. This does not extrapolate to other areas, but it only takes a handful of bad experiences — especially back 10 or 20 years ago when library implementations were so much worse — to convince someone not to waste their time investigating and benchmarking when it is so much easier on the time-financials tradeoff to just assume it is godawful trash and write something quick ‘n’ dirty that was going to perform better anyways.

What a time to be alive trying to ask people to use Standard C and C++, when they can throw a junior developer at a problem at get better performance and compilation times to do a very normal and standard thing like convert to UTF-8.

I certainly don’t endorse the attitude of taking 20 year old perceptions and applying them to vastly improved modern infrastructure that has demonstrably changed, but it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see how we ended up on this particular horizon of understanding.

But, That Done and Dusts That

C and C++ are now Officially Critiqued™ and hopefully I don’t have to have anyone crawl out of the woodwork to talk about X or Y thing again and how I’m not being fair enough by just calling it outright garbage. Now, all of us should thoroughly understand why it’s garbage and how unusable it is.

Nevertheless, if these APIs are garbage, how do we build our own good one? Clearly, if I have all of this evidence and all of these opinions, assuredly I’ve been able to make a better API? So, let’s try to dig in on that. I already figured out the C++ API in ztd.text and written about it extensively, so let’s cook up ztd.cuneicode (or just cuneicode), from the ground up, with a good interface.

A Wonderful API

For a C function, we need to have 4 capabilities, as outlined by the table above.

- Single conversions, to transcode one indivisible unit of information at a time.

- Bulk conversions, to transcode a large buffer as fast as possible (a speed optimization over single conversion with the same properties).

- Validation, to check whether an input is valid and can be converted to the output encoding (or where there an error would occur in the input if some part is invalid).

- Counting, to know how much output is needed (often with an indication of where an error would occur in the input, if the full input can’t be counted successfully).

We also know from the ztd.text blog post and design documentation, as well as the analysis from the previous blog post and the above table, that we need to provide specific information for the given capabilities:

- how much input was consumed (even in the case of an error);

- how much output was written (even in the case of an error);

- that “input read” should only include how much was successfully read (e.g., stops before the error happens and should not be a partial read);

- that “output written” should only include how much was successfully converted (e.g., points to just after the last successful serialization, and not any partial writes); and,

- that we may need additional state associated with a given encoding to handle it properly (any specific “shift sequences” or held-onto state; we’ll talk about this more thoroughly when demonstrating the new API).

It turns out that there is already one C API that does most of what we want design-wise, even if its potential was not realized by the people who worked on it and standardized its interface in POSIX!

Borrowing Perfection

This library has the perfect interface design and principles with — as is standard with most C APIs — the worst actual execution on said design. To review, let’s take a look at the libiconv conversion interface:

size_t iconv(

iconv_t cd, // any necessary custom information and state

char ** inbuf, // an input buffer and how far we have progressed

size_t * inbytesleft, // the size of the input buffer and how much is left

char ** outbuf, // an output buffer and how far we have progressed

size_t * outbytesleft); // the size of the output buffer and how much is left

As stated in Part 1, while the libiconv library itself will fail to utilize the interface for the purposes we will list just below, we ourselves can adapt it to do these kinds of operations:

- normal output writing (

iconv(cd, inbuf, inbytesleft, outbuf, outbytesleft)); - unbounded output writing (

iconv(cd, inbuf, inbytesleft, outbuf, nullptr)); - output size counting (

iconv(cd, inbuf, inbytesleft, nullptr, outbytesleft)); and, - input validation (

iconv(cd, inbuf, inbytesleft, nullptr, nullptr)).

Unfortunately, what is missing most from this API is the “single” conversion handling. But, you can always create a bulk conversion by wrapping a one-off conversion, or create a one-off conversion by wrapping a bulk conversion (with severe performance implications either way). We’ll add that to the list of things to include when we hijack and re-do this API.

So, at least for a C-style API, we need 2 separate class of functions for one-off and bulk-conversion. In Standard C, they did this by having mbrtowc (without an s to signify the one-at-a-time conversion nature) and by having mbsrtowcs (with an s to signify a whole-string conversion). Finally, the last missing piece here is an “assume valid” conversion. We can achieve this by providing a flag or a boolean on the “state”; in the case of iconv_t cd, it would be done at the time when the iconv_t cd object is generated. For the Standard C APIs, it could be baked into the mbstate_t type (though they would likely never, because adding that might change how big the struct is, and thus destroy ABI).

With all of this in mind, we can start a conversion effort for all of the fixed conversions. When I say “fixed”, I mean conversions from a specific encoding to another, known before we compile. These will be meant to replace the C conversions of the same style such as mbrtowc or c8rtomb, and fill in the places they never did (including e.g. single vs. bulk conversions). Some of these known encodings will still be linked to runtime based encodings that are based on the locale. But, rather than using them and needing to praying to the heaven’s the internal Multibyte C Encoding is UTF-8 (like with the aforementioned wcrtomb -> mbrtoc8/16/32 style of conversions), we’ll just provide a direction conversion routine and cut out the wchar_t encoding/multibyte encoding middle man.

Static Conversion Functions for C

The function names here are going to be kind of gross, but they will be “idiomatic” standard C. We will be using the same established prefixes from the C Standard group of functions, with some slight modifications to the mb and wc ones to allow for sufficient differentiation from the existing standard ones. Plus, we will be adding a “namespace” (in C, that means just adding a prefix) of cnc_ (for “cuneicode”), as well as adding the letter n to indicate that these are explicitly the “sized” functions (much like strncpy and friends) and that we are not dealing with null terminators at all in this API. Thusly, we end up with functions that look like this:

// Single conversion

cnc_XnrtoYn(size_t* p_destination_buffer_len,

CharY** p_maybe_destination_buffer,

size_t* p_source_buffer_len,

CharX** p_source_buffer,

cnc_mcstate_t* p_state);

// Bulk conversion

cnc_XsnrtoYsn(size_t* p_destination_buffer_len,

CharY** p_maybe_destination_buffer,

size_t* p_source_buffer_len,

CharX** p_source_buffer,

cnc_mcstate_t* p_state);

As shown, the s indicates that we are processing as many elements as possible (historically, s would stand for string here). The tags that replace X and Y in the function names, and their associated CharX and CharY types, are:

| Tags | Character Type | Default Associated Encoding |

mc |

char |

Execution (Locale) Encoding |

mwc |

wchar_t |

Wide Execution (Locale) Encoding |

c8 |

char8_t/unsigned char |

UTF-8 |

c16 |

char16_t |

UTF-16 |

c32 |

char32_t |

UTF-32 |

The optional encoding suffix is for the left-hand-side (from, X) encoding first, before the right-hand side (to, Y) encoding. If the encoding is the default associated encoding, then it can be left off. If it may be ambiguous which tag is referring to which optional encoding suffix, both encoding suffixes are provided. The reason we do not use mb or wc (like pre-existing C functions) is because those prefixes are tainted forever by API and ABI constraints in the C standard to refer to “bullshit multibyte encoding limited by a maximum output of MB_MAX_LEN”, and “can only ever output 1 value and is insufficient even if it is picked to be UTF-32”, respectively. The new name “mc” stands for “multi character”, and “mwc” stands for — you guessed it — “multi wide character”, to make it explicitly clear there’s multiple values that will be going into and coming out of these functions.

This means that if we want to convert from UTF-8 to UTF-16, bulk, the function to call is cnc_c8snrtoc16sn(…). Similarly, converting from the Wide Execution Encoding to UTF-32 (non-bulk) would be cnc_mwcnrtoc32n(…). There is, however, a caveat: at times, you may not be able to differentiate solely based on the encodings present, rather than the character type. In those cases, particularly for legacy encodings, the naming scheme is extended by adding an additional suffix directly specifying the encoding of one or both of the ends of the conversion. For example, a function that deliberate encodings from Punycode (RFC) to UTF-32 (non-bulk) would be spelled cnc_mcnrtoc32n_punycode(…) and use char for CharX and char32_t for CharY. A function to convert specifically from SHIFT-JIS to EUC-JP (in bulk) would be spelled cnc_mcsnrtomcsn_shift_jis_euc_jp(…) and use char for both CharX and CharY. Furthermore, since people like to use char for UTF-8 despite associated troubles with char’s signedness, a function converting from UTF-8 to UTF-16 in this style would be cnc_mcsnrtoc16sn_utf8(…). The function that converts the execution encoding to char-based UTF-8 is cnc_mcsnrtomcsn_exec_utf8(…).

The names are definitely a mouthful, but it covers all of the names we could need for any given encoding pair for the functions that are named at compile-time and do not go through a system similar to libiconv. Given this naming scheme, we can stamp out all the core functions between the 5 core encodings present on C and C++-based, locale-heavy systems (UTF-8, UTF-16, UTF-32, Execution Encoding, and Wide Execution Encoding), and have room for additional functions using specific names.

Finally, there is the matter of “conversions where the input is assumed good and valid”. In ztd.text, you get this from using the ztd::text::assume_valid_handler error handler object and its associated type. Because we do not have templates and we cannot provide type-based, compile-time polymorphism without literally writing a completely new function, cnc_mcstate_t has a function that will set its “assume valid” state. The proper = {} init of cnc_mcstate_t will keep it off as normal. But you can set it explicitly using the function, which helps us cover the “input is valid” bit.

Given all of this, we can demonstrate a small usage of the API here:

#include <ztd/cuneicode.h>

#include <ztd/idk/size.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

#include <string.h>

int main() {

const char32_t input_data[] = U"Bark Bark Bark 🐕🦺!";

char output_data[ztd_c_array_size(input_data) * 4] = {};

cnc_mcstate_t state = {};

// set the "do UB shit if invalid" bit to true

cnc_mcstate_set_assume_valid(&state, true);

const size_t starting_input_size = ztd_c_string_array_size(input_data);

size_t input_size = starting_input_size;

const char32_t* input = input_data;

const size_t starting_output_size = ztd_c_array_size(output_data);

size_t output_size = starting_output_size;

char* output = output_data;

cnc_mcerror err = cnc_c32snrtomcsn_utf8(

&output_size, &output, &input_size, &input, &state);

const bool has_err = err != cnc_mcerr_ok;

const size_t input_read = starting_input_size - input_size;

const size_t output_written = starting_output_size - output_size;

const char* const conversion_result_title_str = (has_err

? "Conversion failed... \xF0\x9F\x98\xAD" // UTF-8 bytes for 😭

: "Conversion succeeded \xF0\x9F\x8E\x89"); // UTF-8 bytes for 🎉

const size_t conversion_result_title_str_size

= strlen(conversion_result_title_str);

// Use fwrite to prevent conversions / locale-sensitive-probing from

// fprintf family of functions

fwrite(conversion_result_title_str, sizeof(*conversion_result_title_str),

conversion_result_title_str_size, has_err ? stderr : stdout);

fprintf(has_err ? stderr : stdout,

"\n\tRead: %zu %zu-bit elements"

"\n\tWrote: %zu %zu-bit elements\n",

(size_t)(input_read), (size_t)(sizeof(*input) * CHAR_BIT),

(size_t)(output_written), (size_t)(sizeof(*output) * CHAR_BIT));

fprintf(stdout, "%s Conversion Result:\n", has_err ? "Partial" : "Complete");

fwrite(output_data, sizeof(*output_data), output_written, stdout);

// The stream is (possibly) line-buffered, so make sure an extra "\n" is written

// out; this is actually critical for some forms of stdout/stderr mirrors. They

// won't show the last line even if you manually call fflush(…) !

fwrite("\n", sizeof(char), 1, stdout);

return has_err ? 1 : 0;

}

Which (on a terminal that hasn’t lost its mind6) produces the following output:

Conversion succeeded 🎉:

Read: 19 32-bit elements

Wrote: 27 8-bit elements

Complete Conversion Result:

Bark Bark Bark 🐕🦺!

Of course, some readers may have a question about how the example is written. Two things, in particular…

fwrite? Huh??

The reason we always write out Unicode data using fwrite rather than fprintf/printf or similar is because on Microsoft Windows, the default assumption of input strings is that they have a locale encoding. In order to have that data reach specific kinds of terminals, certain terminal implementations on Windows will attempt to convert from what they suspect the encoding of the application’s strings are (e.g., from %s/%*.s) to the encoding of the terminal. In almost all cases, this assumption is wrong when you have a capable terminal (such as the new Windows Terminal, or the dozens of terminal emulators that run on Windows). The C Standard for fprintf and its %s modifier specifies no conversions, but it does not explicitly forbid them from doing this, either. They are also under no obligation to properly identify what the input encoding that goes into the terminal is either.

For example, even if I put UTF-8 data into fprintf("%s", (const char*)u8"🐈 meow 🐱");, it can assume that the data I put in is not UTF-8 but, in fact, ISO 8859-1 or Mac Cyrillic or GBK. This is, of course, flagrantly wrong for our given example. But, it doesn’t matter: it will misinterpret that data as one kind of encoding and blindly encode it to whatever the internal Terminal encoding is (which is probably UTF-16 or some adjacent flavor thereof).

The result is that you will get a bunch of weird symbols or a bunch of empty cells in your terminal, leading to confused users and no Unicode-capable output. So, the cross-platform solution is to use fwrite specifically for data that we expect implementations like Microsoft will mangle on various terminal displays (such as in VSCode, Microsoft Terminal, or just plain ol’ cmd.exe that is updated enough and under the right settings). This bypasses any internal %s decoding that happens, and basically shoves the bytes as-is straight to the terminal. Given it is just a sequence of bytes going to the terminal, it will be decoded directly by the display functions of the terminal and the shown cells, at least for the new Windows Terminal, will show us UTF-8 output.

It’s not ideal and it makes the examples a lot less readable and tangible, but that is (unfortunately) how it is.

What is with the "foo" string literal but the e.g. \xF0\x9F\x98\xAD sequence??

Let us take yet another look at this very frustrating initialization:

// …

const char* const conversion_result_title_str = (has_err

? "Conversion failed... \xF0\x9F\x98\xAD" // UTF-8 bytes for 😭

: "Conversion succeeded \xF0\x9F\x8E\x89"); // UTF-8 bytes for 🎉

// …

You might look at this and be confused. And, rightly, you should be: why not just use a u8"" string literal? And, with that u8"" literal, why not just use e.g. u8"Blah blah\U0001F62D" to get the crying face? Well, unfortunately, I regret to inform you that

MSVC is At It Again!

Let’s start with just using u8"" and trying to put the crying face into the string literal, directly:

// …

const char very_normal[] = u8"😭";

// …

This seems like the normal way of doing things. Compile on GCC? Works fine. Compile on Clang? Also works fine enough. Compile on MSVC? Well, I hope you brought tissues. If you forget to use the /utf-8 flag, this breaks in fantastic ways. First, it will translate your crying emoji into a sequence of code units that is mangled, at the source level. Then, as the compiler goes forward, a bunch of really fucked up bytes that no longer correspond to the sobbing face emoji (Unicode code point U+0001F62D) will then each individually be treated as its own Unicode code point. So you will get 4 code points, each one more messed up that the last, but it doesn’t stop there, because MSVC — in particular — has a wild behavior. The size of the string literal here won’t be 4 (number of mangled bytes) + 1 (null terminator) to have sizeof(very_normal) be 5. No, the sizeof(very_normal) here is NINE (9)!

See, Microsoft did this funny thing where, inside of the u8"", each byte is not considered as part of a sequence. Each byte is considered its own Unicode code point, all by itself. So the 4 fucked up bytes (plus null terminator) are each treated as distinct, individual code points (and not a sequence of code units). Each of these is then expanded out to their UTF-8 representation, one at a time. Since the high bit is set on all of these, each “code point” effectively translates to a double-byte UTF-8 sequence. Now, normally, that’s like… whatever, right? We didn’t specify /utf-8, so we’re getting garbage into our string literal at some super early stage in the lexing of the source. “Aha!”, you say. “I will inject each byte, one at a time, using a \xHH sequence, where HH is a 0-255 hexadecimal character.” And you would be right on Clang. And right on GCC. And right according to the C and C++ standard. You would even be correct if it was an L"" string literal, where it would insert one code unit corresponding to that sequence. But if you type this:

// …

const char very_normal[] = u8"\xF0\x9F\x98\xAD";

// …

You would not be correct on MSVC.

The above code snippet is what folks typically reach for, when they cannot guarantee /utf-8 or /source-charset=.65001 (the Microsoft Codepage name for UTF-8). “If I can just inject the bytes, I can get a u8"" string literal, typed according with unsigned values, converted into my const char[] array.” This makes sense. This is what people do, to have cross-platform source code that will work everywhere, including places that were slow to adopt \U... sequences. It’s a precise storage of the bytes, and each \x fits for each character.

But it won’t work on MSVC.

The sizeof(very_normal) here, even with /utf-8 specified, is still 9. This is because, as the previous example shows up, it treats each code unit here as being a full code point. These are all high-bits-set values, and thus are treated as 2-byte UTF-8 sequences, plus the null terminator. No other compiler does this. MSVC does not have this behavior even for its other string literal types; it’s just with UTF-8 they pull this. So even if you can’t have u8"😭" in your source code — and you try to place it into the string in an entirely agnostic way that gets around bad source encoding — it will still punch you in the face. This is not standards-conforming. It was never standards-conforming, but to be doubly sure the wording around this in both C and C++ was clarified in recent additions to make it extremely clear this is not the right behavior.

There are open bug reports against MSVC for this. There were also bug reports against the implementation before they nuked their bug tracker and swapped to the current Visual Studio Voice. I was there, when I was not involved in the standard and code-young to get what was going on. Back when the libogonek author and others tried to file against MSVC about this behavior. Back when the “CTP”s were still a thing MSVC was doing.

They won’t fix this. The standard means nothing here; they just don’t give a shit. Could be because of source compatibility reasons. But even if it’s a source compatibility issue, they won’t even lock a standards conforming behavior behind a flag. /permissive- won’t fix it. /utf-8 won’t fix it. There’s no /Zc:unfuck-my-u8-literals-please flag. Nothing. The behavior will remain. It will screw up every piece of testing code you have written to test for specific patterns in your strings while you’re trying to make sure the types are correct. There is nothing you can do but resign yourself to not using u8"" anymore for those use cases.

Removing the u8 in front gets the desired result. Using const char very_normal[] = u8"\U0001F62D"; also works, except that only applies if you’re writing UTF-8 exactly. If you’re trying to set up e.g. an MUTF-8 null terminator (to work with Android/Java UTF-8 strings) inside of your string literal to do a quick operation? If you want to insert some “false” bytes in your test suite’s strings to check if your function works? …

Hah.

Stack that with the recent char8_t type changes for u8"", and it’s a regular dumpster fire on most platforms to program around for the latest C++ version.

Nevertheless!

This manages to cover the canonical conversions between most of the known encodings that come out of the C standard:

| mc | mwc | c8 | c16 | c32 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mc | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| mwc | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| c8 | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| c16 | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| c32 | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| mcs | mwcs | c8s | c16s | c32s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mcs | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| mwcs | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| c8s | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| c16s | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| c32s | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

Anything else has the special suffix added, but ultimately it is not incredibly satisfactory. After all, part of the wonderful magic of ztd.text and libogonek is the fact that — at compile-time — they could connect 2 encodings together. Now, there’s likely not a way to fully connect 2 encodings at compile-time in C without some of the most disgusting macros I would ever write being spawned from the deepest pits of hell. And, I would likely need an extension or two, like Blocks or Statement Expressions, to make it work out nicely so that it could be used everywhere a normal function call/expression is expected.

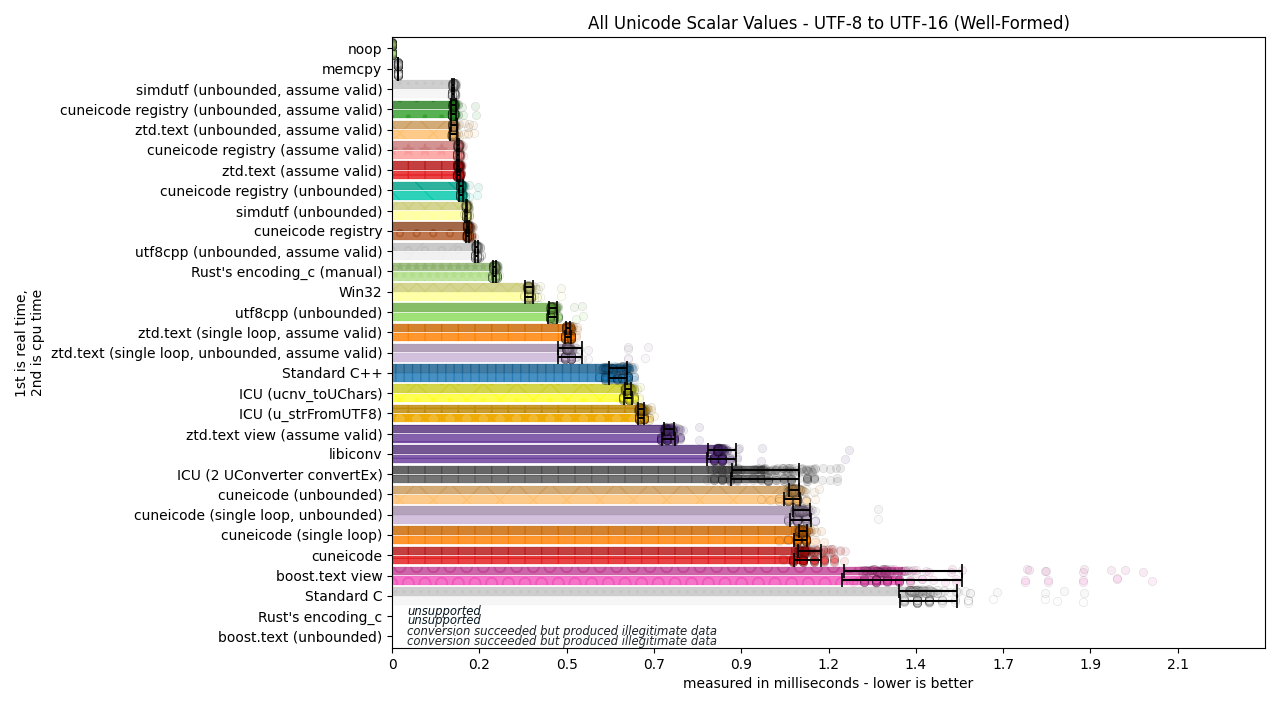

Nevertheless, not all is lost. I promised an interface that could automatically connect 2 disparate encodings, similar to how ztd::text::transcode(…) can give to the ability to convert between a freshly-created Shift-JIS and UTF-8 without writing that specific conversion routine yourself. This is critical functionality, because it is the step beyond what Rust libraries like encoding_rs offer, and outstrips what libraries like simdutf, utf8cpp, or Standard C could ever offer. If we do it right, it can even outstrip libiconv, where there is a fixed set of encodings defined by the owner of the libiconv implementation that cannot be extended without recompiling the library and building in new routines. ICU includes functionality to connect two disparate encodings, but the library must be modified/recompiled to include new encoding routines, even if they have the ucnv_ConvertEx function that takes any 2 disparate encodings and transcodes through UChars (UTF-16). Part of the promise of this article was that we could not only achieve maximum speed, but allow for an infinity of conversions within C.

So let’s build the C version of all of this.

General-Purpose Interconnected Conversions Require Genericity

The collection of the cuneicode functions above are both strongly-typed and the encoding is known. In most cases (save for the internal execution and wide execution encodings, where things may be a bit ambiguous to an end-user (but not for the standard library vendor)), there is no need for any intermediate conversion steps. They do not need any potential intermediate storage because both ends of the transcoding operation are known. libiconv provides us with a good idea for what the input and output needs to look like, but having a generic pivot is a different matter. ICU and a few other libraries have an explicit pivot source; other libraries (like encoding_rs) want you to coordinate the conversion from the disparate encoding to UTF-8 or UTF-16 and then to the destination encoding yourself (and therefore provide your own UTF-8/16 pivot). Here’s how ICU does it in its ucnv_convertEx API:

U_CAPI void ucnv_convertEx(

UConverter *targetCnv, UConverter *sourceCnv, // converters describing the encodings

char **target, const char *targetLimit, // destination

const char **source, const char *sourceLimit, // source data

UChar *pivotStart, UChar **pivotSource, UChar **pivotTarget, const UChar *pivotLimit, // ❗❗ the pivot ❗❗

UBool reset, UBool flush, UErrorCode *pErrorCode); // error code out-parameter

The buffers have to be type-erased, which means either providing void*, aliasing-capable7 char*, or aliasing-capable unsigned char*. (Aliasing is when a pointer to one type is used to look at the data of a fundamentally different type; only char and unsigned char can do that, and std::byte if C++ is on the table.) After we type-erase the buffers so that we can work on a “byte” level, we then need to develop what ICU calls UConverters. Converters effectively handle converting between their desired representation (e.g., SHIFT-JIS or EUC-KR) and transport to a given neutral middle-ground encoding (such as UTF-32, UTF-16, or UTF-8). In the case of ICU, they convert to UChar objects, which are at-least 16-bit sized objects which can hold UTF-16 code units for UTF-16 encoded data. This becomes the Unicode-based anchor through which all communication happens, and why it is named the “pivot”.

Pivoting: Getting from A to B, through C

ICU is not the first library to come up with this. Featured in libiconv, libogonek, my own libraries, encoding_rs (in the examples, but not the API itself), and more, libraries have been using this “pivoting” technique for coming up on a decade and a half now. It is effectively the same platonic ideal of “so long as there is a common, universal encoding that can handle the input data, we will make sure there is an encoding route from A to this ideal intermediate, and then go to B through said intermediate”. Let’s take a look at ucnv_convertEx from ICU again:

U_CAPI void ucnv_convertEx (UConverter *targetCnv, UConverter *sourceCnv,

char **target, const char *targetLimit,

const char **source, const char *sourceLimit,

UChar *pivotStart, UChar **pivotSource, UChar **pivotTarget, // pivot / indirect

const UChar *pivotLimit,

UBool reset, UBool flush, UErrorCode *pErrorCode);

The pivot is typed as various levels of UChar pointers, where UChar is a stand-in for a type wide enough to hold 16 bits (like uint_least16_t). More specifically, the UChar-based pivot buffer is meant to be the place where UTF-16 intermediate data is stored when there is no direct conversion between two encodings. The iconv library has the same idea, except it does not expose the pivot buffer to you. Emphasis mine:

It provides support for the encodings…

… [huuuuge list] …

It can convert from any of these encodings to any other, through Unicode conversion.

— GNU version of libiconv, May 21st, 2023

In fact, depending on what library you use, you can be dealing with a “pivot”, “substrate”, or “go-between” encoding that usually ends up being one of UTF-8, UTF-16, or UTF-32. Occasionally, non-Unicode pivots can be used as well but they are exceedingly rare as they often do not accommodate characters from both sides of the equation, in a way that Unicode does (or gives room to). Still, just because somebody writes a few decades-old libraries and frameworks around it, doesn’t necessarily prove that pivots are the most useful technique. So, are pivots actually useful?

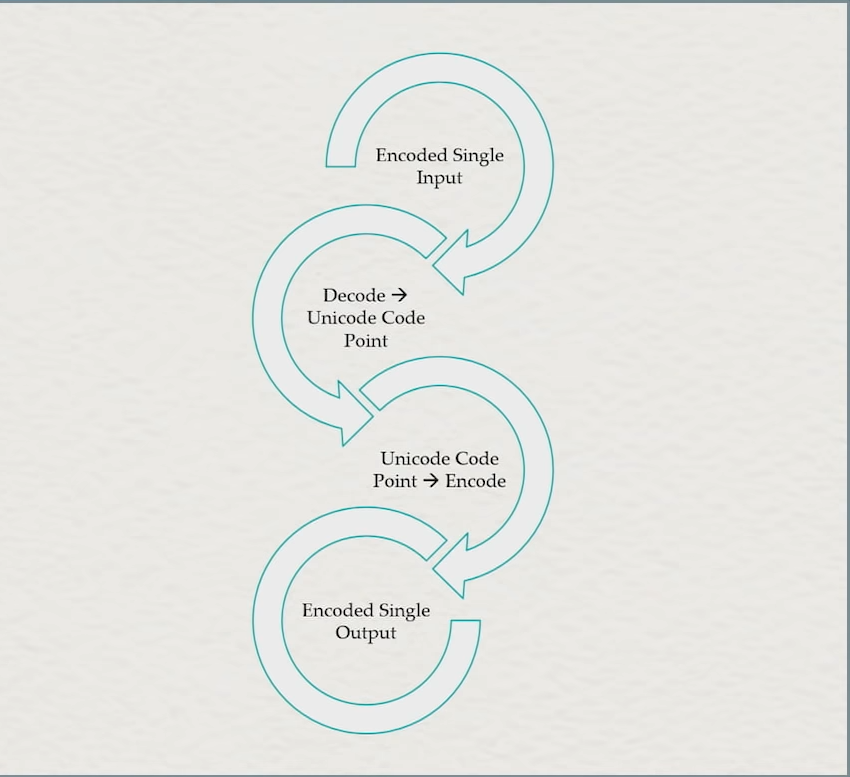

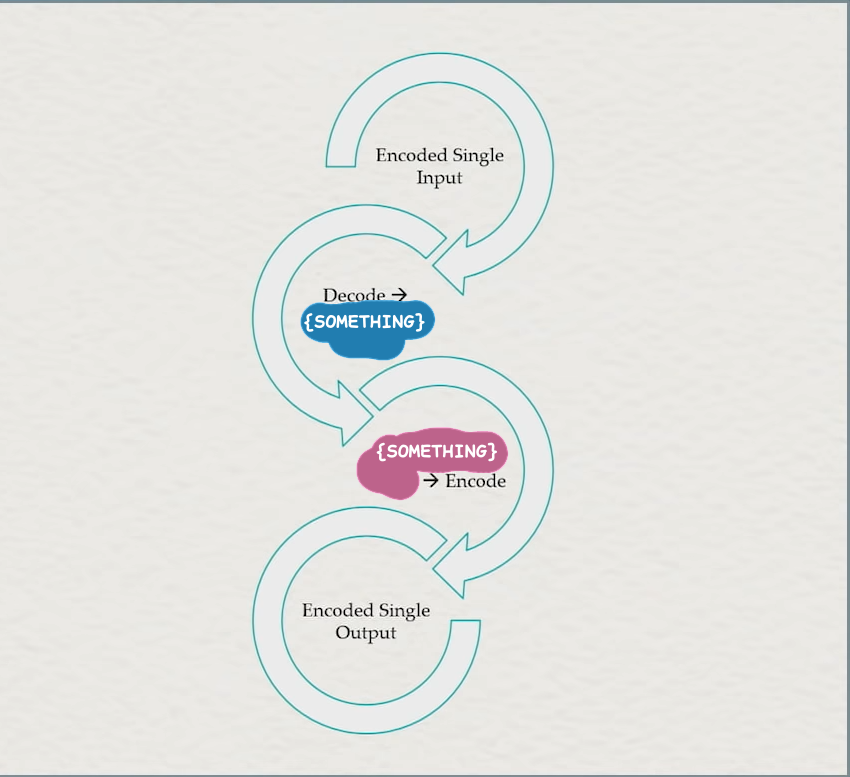

When I wrote my previous article about generic conversions, we used the concept of a UTF-32-based pivot to convert between UTF-8 and Shift-JIS, without either encoding routine knowing about the other. Of course, because this is C and we do not have ugly templates, we cannot use the compile-time checking to make sure the decode_one of one “Lucky 7” object and the encode_one of the other “Lucky 7” object lines up. So, we instead need a system where encodings pairs identify themselves in some way, and then identify that as the pivot point. That is, for this diagram:

And make the slight modification that allows for this:

The “something” is our indirect encoding, and it will also be used as the pivot. Of course, we still can’t know what that pivot will be, so we will once again use a type-erased bucket of information for that. Ultimately, our final API for doing this will look like this:

#include <stddef.h>

typedef enum cnc_mcerror {

cnc_mcerr_ok = 0,

cnc_mcerr_invalid_sequence = 1,

cnc_mcerr_incomplete_input = 2,

cnc_mcerr_insufficient_output = 3

} cnc_mcerror;

struct cnc_conversion;

typedef struct cnc_conversion cnc_conversion;

typedef struct cnc_pivot_info {

size_t bytes_size;

unsigned char* bytes;

cnc_mcerror error;

} cnc_pivot_info;

cnc_mcerror cnc_conv_one_pivot(cnc_conversion* conversion,

size_t* p_output_bytes_size, unsigned char** p_output_bytes,

size_t* p_input_bytes_size, const unsigned char** p_input_bytes,

cnc_pivot_info* p_pivot_info);

cnc_mcerror cnc_conv_pivot(cnc_conversion* conversion,

size_t* p_output_bytes_size, unsigned char** p_output_bytes,

size_t* p_input_bytes_size, const unsigned char** p_input_bytes,

cnc_pivot_info* p_pivot_info);

The _one suffixed function does one-by-one conversions, and the other is for bulk conversions. We can see that the API shape here looks pretty much exactly like libiconv, with the extra addition of the cnc_pivot_info structure for the ability to control how much space is dedicated to the pivot. If p_pivot_info->bytes is a null pointer, or p_pivot_info is, itself, a null pointer, then it will just use some implementation-defined, internal buffer for a pivot. From this single function, we can spawn the entire batch of functionality we initially yearned for in libiconv. But, rather than force you to write nullptr/NULL in the exact-right spot of the cnc_conv_pivot function, we instead just provide you everything you need anyways:

// cnc_conv bulk variants

cnc_mcerror cnc_conv(cnc_conversion* conversion,

size_t* p_output_bytes_size, unsigned char** p_output_bytes,

size_t* p_input_bytes_size, const unsigned char** p_input_bytes);

cnc_mcerror cnc_conv_count_pivot(cnc_conversion* conversion,

size_t* p_output_bytes_size,

size_t* p_input_bytes_size, const unsigned char** p_input_bytes,

cnc_pivot_info* p_pivot_info);

cnc_mcerror cnc_conv_count(cnc_conversion* conversion,

size_t* p_output_bytes_size,

size_t* p_input_bytes_size, const unsigned char** p_input_bytes);

bool cnc_conv_is_valid_pivot(cnc_conversion* conversion,

size_t* p_input_bytes_size, const unsigned char** p_input_bytes,

cnc_pivot_info* p_pivot_info);

bool cnc_conv_is_valid(cnc_conversion* conversion,

size_t* p_input_bytes_size, const unsigned char** p_input_bytes);

cnc_mcerror cnc_conv_unbounded_pivot( cnc_conversion* conversion,

unsigned char** p_output_bytes,

size_t* p_input_bytes_size, const unsigned char** p_input_bytes,

cnc_pivot_info* p_pivot_info);

cnc_mcerror cnc_conv_unbounded(cnc_conversion* conversion,

unsigned char** p_output_bytes,

size_t* p_input_bytes_size, const unsigned char** p_input_bytes);

// cnc_conv_one single variants

cnc_mcerror cnc_conv_one(cnc_conversion* conversion,

size_t* p_output_bytes_size, unsigned char** p_output_bytes,

size_t* p_input_bytes_size, const unsigned char** p_input_bytes);

cnc_mcerror cnc_conv_one_count_pivot(cnc_conversion* conversion,

size_t* p_output_bytes_size,

size_t* p_input_bytes_size, const unsigned char** p_input_bytes,

cnc_pivot_info* p_pivot_info);

cnc_mcerror cnc_conv_one_count(cnc_conversion* conversion,

size_t* p_output_bytes_size,

size_t* p_input_bytes_size, const unsigned char** p_input_bytes);

bool cnc_conv_one_is_valid_pivot(cnc_conversion* conversion,

size_t* p_input_bytes_size, const unsigned char** p_input_bytes,

cnc_pivot_info* p_pivot_info);

bool cnc_conv_one_is_valid(cnc_conversion* conversion,

size_t* p_input_bytes_size, const unsigned char** p_input_bytes);

cnc_mcerror cnc_conv_one_unbounded_pivot(cnc_conversion* conversion,

unsigned char** p_output_bytes, size_t* p_input_bytes_size,

const unsigned char** p_input_bytes, cnc_pivot_info* p_pivot_info);

cnc_mcerror cnc_conv_one_unbounded(cnc_conversion* conversion,

unsigned char** p_output_bytes,

size_t* p_input_bytes_size, const unsigned char** p_input_bytes);

It’s a lot of declarations, but wouldn’t you be surprised that the internal implementation of almost all of these is just one function call!

bool cnc_conv_is_valid(cnc_conversion* conversion,

size_t* p_bytes_in_count,

const unsigned char** p_bytes_in)

{

cnc_mcerror err = cnc_conv_pivot(conversion,

NULL, NULL,

p_bytes_in_count, p_bytes_in,

NULL);

return err == cnc_mcerr_ok;

}