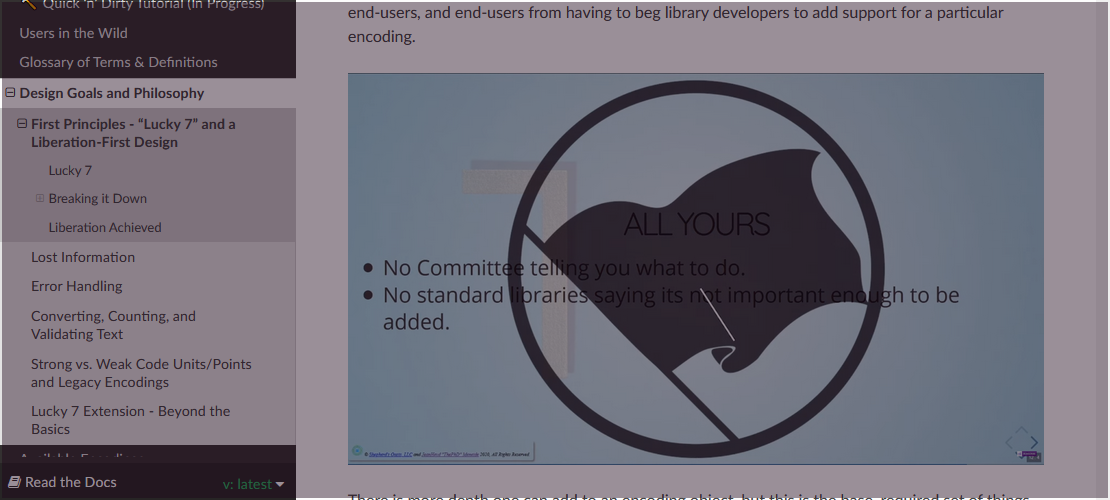

Everything the light touches may not be yours, but by God it very well should be when it comes to text encodings.

I’ve spent the overwhelming part of 2 years talking, advocating, and riffing about C and C++ libraries that put users first. Seriously: conference talks, interviews, C and C++ proposals, and more have been the name of the game for the last 2 years as I built an awareness of the struggle that was handling text in a way that wasn’t fundamentally broken for the 2 lowest level programming languages that span most of the industry. The slow, 2-year trickle of tiny donations, e-mails of support from individuals, and more hit enough of a momentum that I could focus it all into a huge burst of strength to create my most well-documented and nice library to-date:

ztd.text

ztd.text is the proof of everything I’ve been blah-blah-blahing and designing and tweaking for the past 2 years. It is my gigantic designer middle finger to everybody’s attempts at (poorly) handing encoding in their libraries and the roving, increasingly rowdy gang of UTF-8 Everywhere proponents who translated that poor developer’s UTF-8 Everywhere advice to be “Only UTF-8, ever, and nothing else”. But, most importantly, it is the final stage of liberation from the encoding hell that our forebears brought down upon our heads. The goal of the library is simple: text encoding, decoding, transcoding, and related operations are single function calls, entirely painless, and infinitely extensible. In other words, this snippet of code will do exactly what you expect it to without a single surprise:

#include <ztd/text.hpp>

#include <string>

#include <string_view>

int main (int argc, char* argv[]) {

if (argc < 2) {

return 1;

}

// get input as UTF-8

std::u8string_view utf8_input(

reinterpret_cast<const char8_t*>(argv[1])

);

std::u16string utf16_output = ztd::text::transcode(

utf8_input, // input

ztd::text::utf16{} // to encoding

);

// dump to stdout

std::cout.write(

reinterpret_cast<const char*>(utf16_output.data()),

utf16_output.size() * sizeof(char16_t)

);

// flush + newline

std::cout << std::endl;

return 0;

}

The encoding of the input is inferred from its code unit type. In this case, it’s char8_t, so we get to assume - without breaking anyone’s back - that it’s UTF-8. This code Just Works™, all the time, across all systems, and will always dump a sequence of UTF-16, Native-Endian, bytes out to your stdout (terminal, redirected file, char device output, whatever). That’s the dream I have realized for C++: a very simple, very normal way of getting the work done here with no judgement. Of course, many people have some complaints/questions when reading this, like:

“Okay, but I hate char8_t and use UTF-8 in char.”

I thought of you many years in advance, don’t you worry:

#include <ztd/text.hpp>

#include <string>

#include <string_view>

int main (int argc, char* argv[]) {

if (argc < 2) {

return 1;

}

// get input (as UTF-8, maybe??)

std::string_view utf8_input(argv[1]);

std::u16string utf16_output = ztd::text::transcode(

utf8_input, // input

ztd::text::compat_utf8{}, // from encoding

ztd::text::utf16{} // to encoding

);

// dump to stdout

std::cout.write(

reinterpret_cast<const char*>(utf16_output.data()),

utf16_output.size() * sizeof(char16_t)

);

// flush + newline

std::cout << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Because the input type is char, we have to specify the “from encoding” explicitly. This is due to the default for char being the locale-based “execution encoding”. On most Linux systems, this ends up being UTF-8. But if you go to Windows, well… your code might break. It may or may not be UTF-8 on all platforms, so to be as completely unambiguous as possible we simply use the “compatibility” UTF-8, that traffics in char rather than char8_t or unsigned char, encoding object to signal our desires. Which gets us what we want: a way to go from a char-based UTF-8 to UTF-16 so we can dump the data to stdout. So, so far, so good! We have flexibility in what to convert, it gives us a std::string back, and all that good stuff. There are additional overloads to transcode and companion functions like transcode_into that allow you to do things like control allocation or control what kind of container comes out on the other side, albeit that’s not very useful for a small demo application. But, it’s there if you want to stare at the documentation. Of course, there’s one really, REALLY important OTHER question people bother me with besides “why don’t you just assume char is UTF-8, all the time”, and that’s…

What about Other/Legacy™ Encodings?

Sure, the library may come bundled with UTF-8/16/32, some legacy helpers, (wide) locale-based execution, and even (wide) string literal based encodings. Unfortunately, if that’s all it has, well, cool story little sheep: is it really worth it?! But. What if I told you, that I could get hit by a giant clown car and die on the spot right this second, and you’d still be able to put any single encoding in the whole planet in this bad boy? That, without knowing what “UTF-8” was, or programming for it, you could transcode any bit of text you wanted to UTF-8, no matter where it came from, without having to specifically write a “X to UTF-8” conversion routine?

Can we? If we can, we have to do it, right? Let’s test the idea that we can stick any encoding - new or old, legacy or not - into this. That we can call ztd::text::transcode with it. That if we were to, say, put some functionality like this in the Standard Library, it would be capable of standing on its two wobbly library knees from now until the inevitable climate inferno or glacial chill kills us all under the auspices of several governments that don’t give a damn. But, what to pick to test this theory? Certainly, there’s so many encodings, and ztd.text supports the “biggest” ones already! But… ah, here’s a missing one, one that’s important to a lot of people!

Let’s implement Shift JIS.

Shift JIS - A Primer

Shift Japanese Industrial Standard - SJIS, but most commonly Shift JIS - is the second most popular encoding for Japanese (.jp) websites. Which is not saying too much, because UTF-8 is in first place with a 92% share of all Japanese websites. Still, at a healthy 6.3%, there’s enough web encoded in it that it’s not exactly unheard of to run into. Also, that is just website data. This ignores the staggering amount of actual user, industrial, and governmental data that hasn’t been transcoded to some Unicode format, nor does it cover the legacy defaults in many machines for end-users that still work with, recognize, and produce Shift JIS by default.

So, we need to leverage a concept that comes from ztd.text that claims if we follow it, we get the ability to go from Shift JIS to UTF-8, UTF-16, even some other disparate encoding. So let’s follow this concept - this “Lucky 7” - and see if it’s possible.

The Lucky 7

The Lucky 7 is a theory that you only need seven (7) things to make the entire ztd.text ecosystem work. By writing something containing these magical seven elements, you are supposed to get:

- encoding, decoding, transcoding (decode/encode between 2 completely unrelated encodings);

- counting for all the above operations;

- validation for all the above operations;

- freestanding/embedded-suitable versions of all the above operations by-default;

- detailed error reporting information;

- and more.

So, can we? Let’s follow the guide at the design page for the “Lucky 7” and see if this concept holds water for an encoding like Shift JIS!

An Encoding Object

The core of ztd.text’s Lucky 7 is, effectively, defining an object with 7 things on it. According to the docs, we need:

- 3 types / type definitions for the value type of the “code units”, for the value type of the “code points”, and for the “state” we need;

- 2

static constexpr size_tvariables, for the maximum potential output of either an encoding operation or a decoding operation; and, - 2 functions, one for encoding (Unicode Code Points into Shift JIS code units) and one for decoding (Shift JIS code units into Unicode Code Points).

Sounds simple enough. The code unit - representing a single piece of encoded data - will probably have a type of char, because that’s the type most Shift JIS text lives in for C and C++ programs. The code point - representing a unit of decoded data - will be a good ol’ Unicode Code Point. unicode_code_point is a mouthful, so we’ll just call it char32_t for now and say it’s fine.

For the 2 static constexpr size_t variables, we just need to know the maximum amount of output we can produce for a single encode or decode operation. Note that this is just enough to produce one complete, uninterrupted unit of information from the stream, such that if someone, say, pulled out the power plug after the operation, the stream would not be in a malformed state. (Malformed here means “could not be re-encoded or re-decoded, if fed back into the function which does the opposite of the last thing you did”.) In this case, “one completely, uninterrupted unit of information” means that we get one whole char32_t out from the Shift JIS decoding process. Or, in the case of encoding, we get 1 or 2 chars, out, since Shift JIS is a double-byte encoding.

And, finally, we need 2 functions. One should be called encode_one and the other is decode_one. As the names imply, they perform a singular complete unit of encoding or decoding. It takes in an input range, an output range (see here for an explanation / performance measurement / rant about output ranges), an error handler, and the current state.

Making a Declaration

So, let’s fill in at least the parts we know! We start with the basic class name and typical includes:

#include <ztd/text.hpp>

#include <cstddef>

#include <span>

#include <functional>

// the Shift JIS encoding

struct shift_jis {

// (1)

using code_unit = char;

// (2)

using code_point = char32_t;

// (3)

struct state {};

// (4)

static constexpr inline std::size_t max_code_points = 1;

// (5)

static constexpr inline std::size_t max_code_units = 2;

/* More... */

};

Alright, that’s the first 5 required pieces. The encoded data comes in chars, the decoded data comes in char32_t, there is no interesting state to hold onto for Shift JIS so it’s an empty type, and the max_code_units represents the appropriate maximum output of 2. max_code_points is 1 because we only ever need to output 1 unicode code point at a time after consuming the minimum required amount of information to produce “one complete unit” of decoded information. Nice! Now, we get to the much more involved part: the encode_one and decode_one functions:

/* includes from before ... */

struct shift_jis {

/* (1) through (5) from before */

// Helper (A)

using sjis_encode_result = ztd::text::encode_result<

std::span<const code_point>, // input range, decoded data

std::span<code_unit>, // output range, encoded data

state // current state

>;

// Helper (B)

using sjis_decode_result = ztd::text::decode_result<

std::span<code_unit>, // input range, decoded data

std::span<const code_point>, // output range, encoded data

state // current state

>;

// Helper (C)

using sjis_encode_error_handler = std::function<sjis_encode_result(

const shift_jis&, // encoding that failed

sjis_encode_result, // result object representing failure

std::span<const code_point> // any code points read-impending discard (unused)

)>;

// Helper (D)

using sjis_decode_error_handler = std::function<sjis_decode_result(

const shift_jis&,

sjis_decode_result, // result object representing failure state

std::span<const code_unit> // any code points read-impending discard (unused)

)>;

// (6)

sjis_encode_result encode_one(

std::span<const code_point> input,

std::span<code_unit> output,

sjis_encode_error_handler error_handler,

state& current_state) const;

// (7)

sjis_decode_result decode_one(

std::span<const code_unit> input,

std::span<code_point> output,

sjis_decode_error_handler error_handler,

state& current_state) const;

}

That’s a lot of Types!

Yes, the encode_one and decode_one functions are the most involved portion of the encoding object. As they should be: they represent where all the magic happens. Let’s talk about each individual piece of the declarations before we get into the nitty gritty of it. Some of it is self-explanatory, but other bits are going to be a little new in terms of API design to some folk. We’ll start with the 2 result declarations (A) and (B), since they’re the simplest.

sjis_encode_result (A) and sjis_decode_result (B)

These are, effectively, the need to have dedicated types with good names for its members. We need to return a lot of information from both the encode_one and decode_one functions about the progress they made and the things they’ve done. A lot of information is common between all encodings, but the 3 template parameters that can change between each kind of encoding is the input type, output type, and given state. Given that, we end up with these members on the types:

- the

Input input;range (in this case, astd::spanof some sort) indicating the values leftover that still have not been read; - the

Output output;range (in this case, astd::spanof some sort) indicating the leftover space that can still be written into; - a

ztd::text::encoding_error error_code;enumeration value indicating whether that particular function call toencode_oneordecode_onesucceeded; - a

std::size_t errors_handledintegral value indicated the number of times an error handler was invoked; and, - a

State& statereference for any data that need to be preserved between calls.

This is everything someone interacting with this low-level part of the API will need to do their various jobs.

For example, the error_code is how a low-level API knows not to continue processing: it simply needs to check if the value is not encoding_error::ok. errors_handled is a value that, even if encoding_error::ok is returned, can be a positive value indicating that the error handler WAS called. This is mostly used in situations where the error handler performs some corrective action that makes it okay to proceed, but would still like to let an inquisitive end-user know that something has gone wrong. For example, if the error handler inserts corrective '?' characters in an ASCII stream, it can be difficult from a programmatic perspective to know if the '?' was intended or if it was part of the text without some very serious and complex Natural Language Processing techniques. It’s much simpler to just get an integer count of the number of times the error handler was, in fact, invoked to know that the stream was not encoded or decoded perfectly! All of this information is passed to the error_handler functions when something goes wrong through the result types, and allows an error handler to perform all of that functionality. Which, speaking of error handlers…

sjis_encode_error_handler (C) and sjis_decode_error_handler (D)

Both of these are just type definitions for std::function, since we want to take any callable that can handle the required parameters and return to us the desired information. Error handler function takes 3 parameters, in this particular order:

- the

Encodingtyped parameter that is calling the error handler (*this); - the

encode_resultordecode_resulttyped parameter, depending on which operation (encode_oneordecode_one) is being performed; and, - a contiguous range (usually a

std::span) representing any data read from the input but that cannot be put back into the input.

The last parameter means almost nothing to most people, and only comes in handy for dealing with very special kinds of non-copyable input_range types when they are the input parameter to encode_one or decode_one. Since we are dealing with span inputs, we can ignore it. The first parameter is just the encoding type. In this case, it’s shift_jis: we don’t really worry about this parameter either, since we’ll just pass *this. But the second parameter?

That’s where the spiciness is.

The second parameter gives you the result object. The type of the second parameter is also the return type for the error handler. The result object is taken in by value, and you are expected to return one of the identical type. Critically, this means the error handler can then do anything it likes with it using the information that was given, then return that result object with its modifications (or not). For example, the error handler can:

- insert replacement characters (like this one);

- accumulate characters read but not used on failure (like this one);

- throw failures as errors (like this one);

- and more!

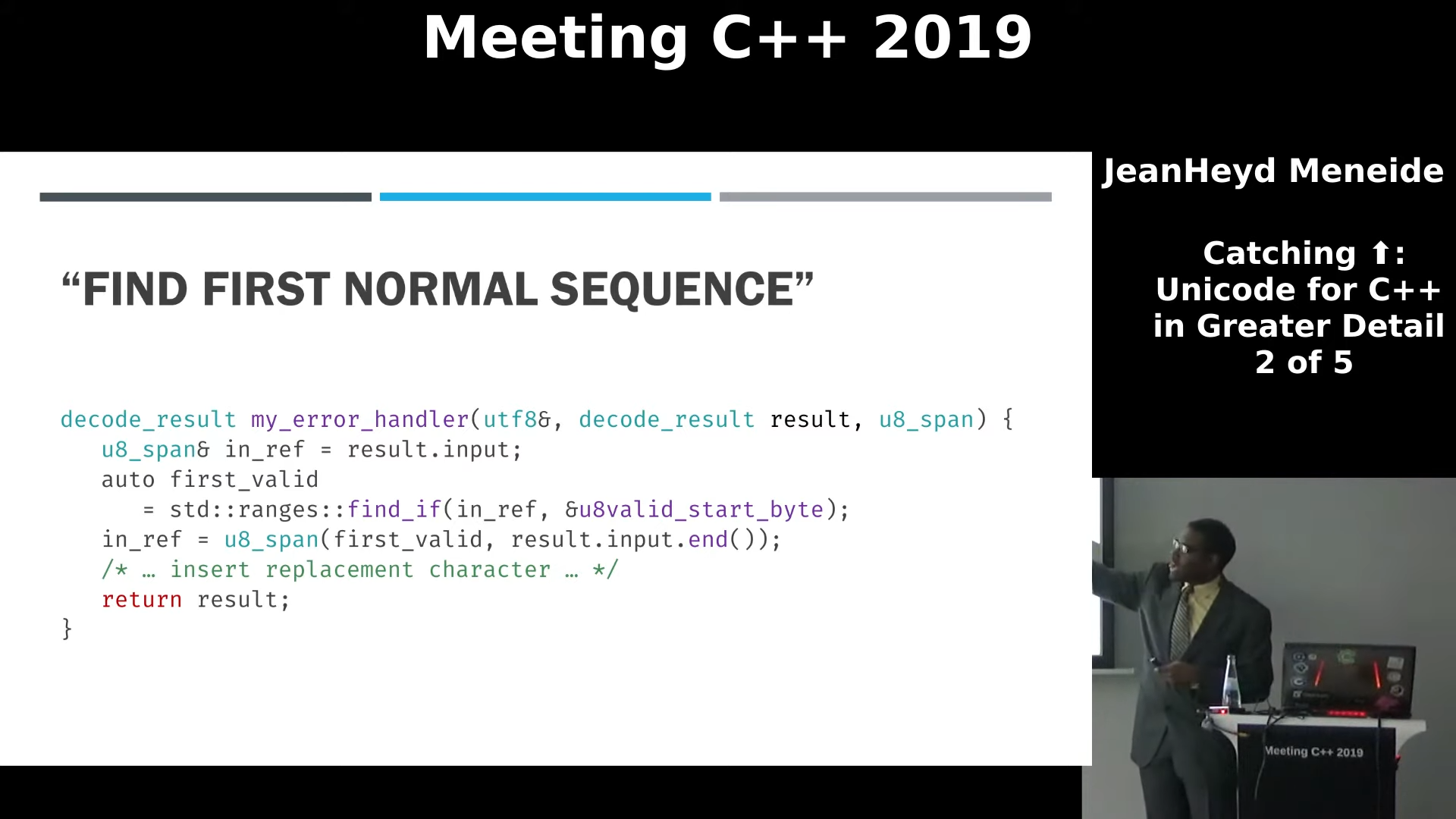

I even gave a presentation where I talked about skipping over invalid bytes, when an error is encountered in a Unicode-stream, to get to the next known good byte (timestamped video link with the picture):

This results in an entirely flexible apparatus for processing errors. When calling it inside of our encode_one or decode_one functions, the error handler function call will look mostly like this:

struct shift_jis {

/* (1) through (5) … */

sjis_encode_result encode_one(

std::span<const code_point> input,

std::span<code_unit> output,

sjis_encode_error_handler error_handler,

state& current_state)

const {

/* work to get iterators to

input, convert to unsigned,

do work,and all that jazz, etc… */

if (output.empty()) {

// output is empty, can't put things in 😔

// call the error handler...

return error_handler(*this, // the encoding!

sjis_encode_result( // the result object, constructed in-place!

std::move(input),

std::move(output),

current_state,

ztd::text::encoding_error::insufficient_output_space

),

std::span<const code_point>() // any read-but-unsued code points!

); // calls the error handler

}

/* rest of implementation */

}

/* decode_one, etc. */

};

Now, the last bit is actually implementing the functions!

encode_one (6) and decode_one (7)

Even as I say “implementing the functions”, I’m not going to actually walk you through implementing all of a shift_jis encoder and decoder: just a few bits. This is mostly because the lovely folks at the WHATWG (Web Hypertext Application Technology Working Group) have written up a good, normal, mostly-plain-English, technical description on how to encode or decode these data streams.

Perhaps the only surprising thing here would be the use of an “output range”, since most people are only used to using a single “output iterator” (e.g., std::copy which only takes a single “destination” iterator or memcpy which only takes a single “destination” pointer). Reading from an input is still similar to breaking something down into its iterators and walking through it, one by one. Safety is expected to be taken care of by the encode_one or decode_one function, e.g. if the input is empty you are expected to bail, not just start reading garbage. This is one of the chief benefits of dealing with ranges: the fact that we get to check our data accesses against an “end” or, if we’re just using input/output ranges directly, we get to use common functions like .empty() or similar. Here is the first bit of the shift_jis::encode_one function, responsible for some brief checking and serializing the first byte if it fits in the “ASCII” part of Shift JIS:

struct shift_jis {

/* (1) through (5) … */

sjis_encode_result encode_one(

std::span<const code_point> input,

std::span<code_unit> output,

sjis_encode_error_handler error_handler,

state& current_state)

const {

using input_span = std::span<const code_point>;

using output_span = std::span<code_unit>;

// Do we have anything to read?

if (input.empty()) {

// we don't need more, so we can just say the empty

// state is a-okay.

return sjis_encode_result(

std::move(input), std::move(output),

current_state,

ztd::text::encoding_error::ok

);

}

// get prepared to get started...

auto in_it = input.begin();

auto in_last = input.end();

auto out_it = output.begin();

auto out_last = output.end();

code_point code = *in_it;

++in_it;

if (code <= 0x80) {

// checked access

if (out_it == out_last) {

// output is empty :(

return error_handler(*this,

sjis_encode_result(

// return original input/output,

// we do not want to claim we successfully

// read the input or wrote any output

std::move(input),

std::move(output),

current_state,

ztd::text::encoding_error::insufficient_output_space

),

input_span()

);

}

// dereference and write

*out_it = static_cast<code_unit>(code);

// increment iterator

++out_it;

return sjis_encode_result(

// re-construct the input and output, using

// the updated iterators, since we were successful!

input_span(std::move(in_it), std::move(in_last)),

output_span(std::move(out_it), std::move(out_last)),

current_state,

ztd::text::encoding_error::ok

);

}

/* handle other cases here... */

}

};

There are a few things to note about this snippet. While when talking about the error cases we filtered the sjis_encode_result through an error_handler call to let it perform an arbitrary action, we do not do that when the returned value is an expected and successful case.

Whew… Alright, Does It Work?

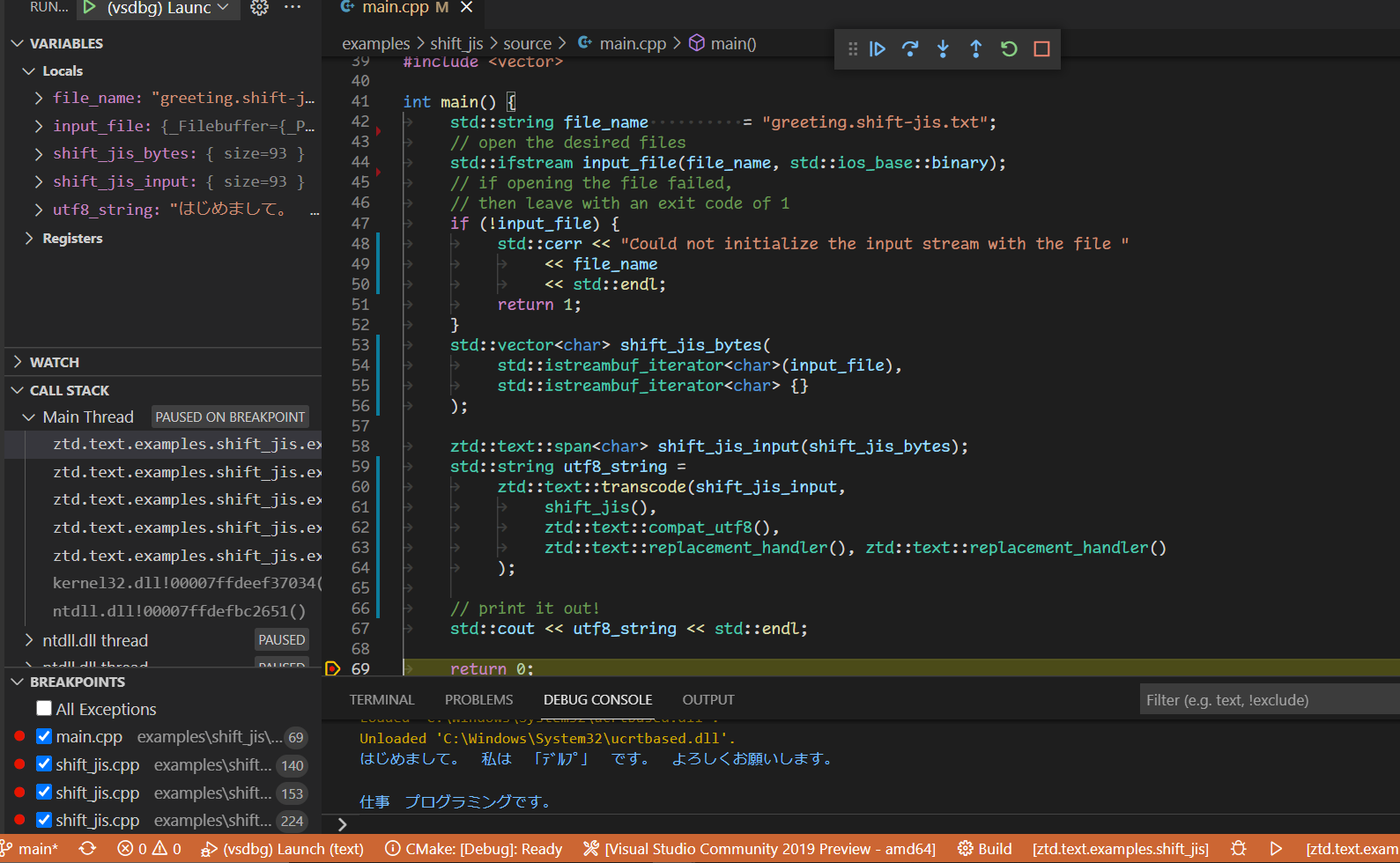

Assuming that you finish up the implementation (or just copy-paste from this example, I won’t judge! 😉), we can now put it to work. I made a Shift JIS file called "greeting.shift-jis.txt" with the following text in it:

はじめまして。 私は 「デルプ」 です。 よろしくお願いします。

仕事 プログラミングです。

We load that file into a std::ifstream, read the bytes into a std::vector<char>, ztd::text::transcode‘d it, and then try to vomit the UTF-8 into a terminal. We use the replacement error handlers to give me an idea of whether or not any replacement characters ('�') would show up to display that our known-correct Shift JIS was fraudulent and would come out bad anywhere:

#include "shift_jis.hpp"

#include <ztd/text.hpp>

#include <fstream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

int main() {

std::string file_name = "greeting.shift-jis.txt";

// open the desired files

std::ifstream input_file(file_name, std::ios_base::binary);

// if opening the file failed,

// then leave with an exit code of 1

if (!input_file) {

std::cerr << "Could not initialize the input stream with the file "

<< file_name

<< std::endl;

return 1;

}

std::vector<char> shift_jis_bytes(

std::istreambuf_iterator<char>(input_file),

std::istreambuf_iterator<char> {}

);

ztd::text::span<char> shift_jis_input(shift_jis_bytes);

std::string utf8_string =

ztd::text::transcode(shift_jis_input,

shift_jis(),

ztd::text::compat_utf8(),

ztd::text::replacement_handler(), ztd::text::replacement_handler()

);

// print it out!

std::cout << utf8_string << std::endl;

return 0;

}

The result:

Of course, I could be doctoring this screenshot. I could be lying. So if you’re a skeptic, don’t take my word for it: touch the grassimplementation for yourself. You will see that the theorem holds, that the corollaries apply, and that we can go from one encoding to a completely unrelated and completely unanticipated encoding without knowing anything about it. It’s not just UTF-8, it can be literally anything:

// an extremely smart person's EBCDIC compatibility layer

std::string utf_ebcdic_string =

ztd::text::transcode(shift_jis_input,

shift_jis(),

edhebi::utf_ebcdic(),

ztd::text::replacement_handler(), ztd::text::replacement_handler()

);

// an external library

std::string big5_hkscs_string =

ztd::text::transcode(shift_jis_input,

shift_jis(),

somebody_else::please_implement::big5_hkscs(),

ztd::text::replacement_handler(), ztd::text::replacement_handler()

);

// rust

std::vector<unsigned char> rust_os_string =

ztd::text::transcode<std::vector<unsigned char>>(shift_jis_input,

shift_jis(),

rst::wtf8(),

ztd::text::replacement_handler(), ztd::text::replacement_handler()

);

// and so on...

You can know any encoding, so long as you provide an encoding object that takes care of your own. You can talk to ztd.text’s encodings, the standard’s encodings, someone else’s encoding, and it will be as if it is your own. This ultimately keeps with my biggest promise, that I have made over and over again while giving talks and fighting against people both inside and outside the C and C++ Committee:

Text is for Everybody

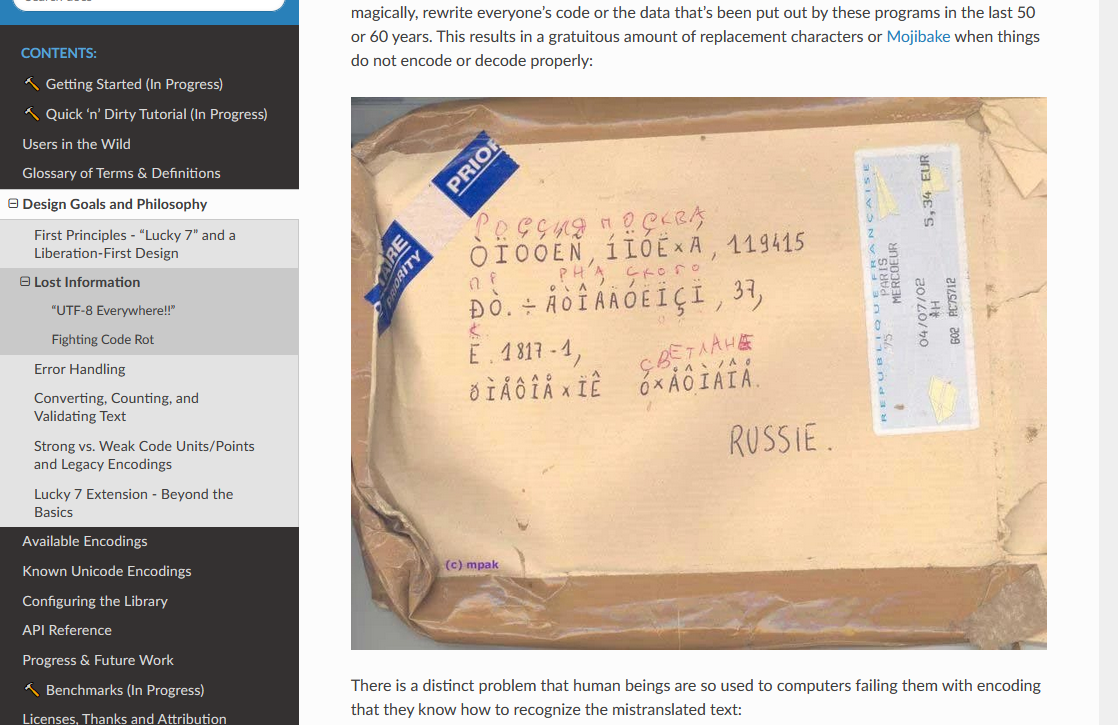

No, text is not just for the Unicode-fortunate. No, text is not meant to only be stored in UTF-8: if that’s the lesson you took from UTF-8 Everywhere, then you didn’t read the full manifesto or understand the nuance at all. The goal of UTF-8 Everywhere is to turn modern applications and the internals of legacy applications into things that primarily use and traffic in Unicode. What it is not is an invitation to isolate those people who do have legacy applications, codebases, and tools and tell them to go pound sand. Unicode is not the only encoding, and while it should be encouraged and given deference and made the default as much as possible, you cannot simply overturn 40+ years of locale-based encodings, databases, tools, and more:

… On the contrary, it would be a mistake to reinvent a new string class and force everyone through your peculiar interface. Of course, if one needs more than just passing strings around, he should then use appropriate text processing tools. However, such tools are better to be independent of the storage class used, in the spirit of the container/algorithm separation in the STL. In fact, some consider

std::stringinterface too bloated, as most of it was better to be moved out of thestd::stringclass.

This Stepanov-level separation between the container and algorithms - the encoding and the storage substrate it’s placed in - is exactly what ztd.text brings to the table, and will continue to bring to the table in the future with basic_text<Encoding, Storage, ...>, basic_text_view<Encoding, Storage, ...>, decode_view/encode_view/transcode_view and more.

But Old Tools are Old!

Oh yeah, these super old tools that have absolutely no relevance today and aren’t causing problems anymore! It’s all legacy stuff, for sure! Honestly, the last time anyone’s used such old tools that screw encoding up are - checks notes - …

Oh. Hmm:

TIL that mysqldump will screw up emojis by default.

Your MySQL backups are broken by default.

I knew that MySQL screws up emojis by default, and you need to create databases as utf8mb4. But it turns out you also need to specify it as a commandline option when making dumps.

Now, the immediate reaction to this is “MySQL sucks”. And I certainly concede, MySQL definitely does suck quite a bit, especially since its utf8 is not real UTF-8 and you need to specify utf8mb4, specifically. But I don’t blame MySQL, oh no. I blame C. It was C that mixed locales with encoding and set the entire C ecosystem on a Babylonian Tower-esque crash course with the rest of the world. It was C++ that then took those mistakes and baked them into the C and C++ APIs that we use today: iostreams, std::to_string, std::isspace, parts of filesystem, and other god awful messes that are invisibly dependent on locale for both localization information and completely inadequate at handling multibyte encodings. And what I hear when someone - especially someone on the C++ Committee - says “we don’t have to care about old encodings”, is:

“I am Willfully Unqualified to Solve This Problem”

In what universe is it fair that you — part of the Committee, the original sinners that created this disgusting ecosystem and all of horrific problems with your failed wchar_t and char-based localization that you crammed into every possible API — condemn everyone? You lead every programmer right to the gates of hell after over 200+ encodings are created and many attached at the language-level to my machine. And when the curse is at its worst and hell’s massive opening mechanism ominously KA-CHNKs open and its gaping maw drools with the screams of the damned, you just give a little peace sign and run off into your Unicode-only heaven. And thus, we stand here to fight the licking, devouring flame and save ourselves as you cavort into paradise? With all due respect,

what the hell is wrong with you?

“But We Didn’t Know Any Better!”

Is this supposed to be a good enough reason to give everyone — who for 30-40+ years, has been cranking out locale-based data because of your designs — a giant middle finger? In what universe is not providing a way out for the people, whose designs you and your forefathers entrapped, a preferable solution? “Well, it wasn’t specifically ME, it was done before my time!” Then why are you in the room deciding what everyone gets to use if you’re not interested in solving the problems of your lineage? If you can’t handle the weight and complexity of the task at hand and the people you now carry on your shoulders,

please leave the room.

You cannot cop out with such excuses, because your choices have REAL WORLD impact:

I’m not going to spend the next 30 years of my life apologizing and bowing my head in shame to a bunch of developers, postal workers, people whose names come out as “MichaÅ”, and other folk because we decided the only encoding that matters is Unicode and everyone else who needs to get to Unicode can pound sand. If you wanted the cheap way out you should have went to go play with a new programming language ecosystem, where everything is new and fresh and untainted and you don’t have to give a damn about legacy and your strings can be UTF-8 all the time. But this is for C and C++, and it’s painful and burdened with legacy and you don’t just get to tell everyone whose been investing in your programming languages for decades to Go Eat Shit Because It’s Unicode Only Time Babyyyy!!

Daiko Ueno, Bruno Haible, rmf, and several others already paved the way and proved out this design decades ago when they released their libraries (iconv, libogonek, and more). People with legacy encodings need a way out too, and denying them that way out because “boo hoo, complexity!” is the worst design cop out I’ve ever had the extreme displeasure of listening to. I refuse to suffer such claims from a body that fashions itself is the pinnacle of Library Designers for code that is meant to Sit Beneath All Devices And Work For Everyone. Do it right, with empathy and conviction for the people you put in this situation, or don’t bother at all. I am not asking for liberation for handling text in C and C++: I am demanding it. It will be given to me and my peers. If not because someone else decided to do it,

then because I did it with my own two hands. 💚

P.S. There will be more posts about ztd.text and all the cool things that can be done with it!! I just had to get all this off my chest, FINALLY.