A tweet popped off, and I kept getting asked a lot of questions about what is or is not in C23. So, I’m going to be bringing everyone up to speed on what’s been changing lately! A previous article covering some what has been changed is available here, which covers things like _BitInt. There’s a whole article about #elifdef and #elifndef and the power of user advocacy.

As a primer, you can get a semi-complete list (modulo the latest stuff) from cppreference and from Wikipedia. Some changes should probably be made to those pages, but I still have to produce a new C Working Draft that has all the agreed upon changes from last meeting and this meeting. Still, there’s a few minor simplifications on both pages that sent a few shocks through the C Community, so there’s a few elaborations I’ll need to make that Twitter’s little character limit isn’t good for! We’ll start with the change that most people are both over-the-moon about, and also terribly worried about:

Revise Spelling of Keywords” | Make false and true First-Class Language Features

Document Numbers: N2934 | N2935

To quote a hardworking C professional of a few decades:

This makes no sense! I’ve been repeatedly told we can’t have nice things in C …

Indeed, it was believed for a long time that such changes could be made. Even as Jens Gustedt - the G.O.A.T. when it comes to fixing older problems in C - fought to put it into the C Standard, you’ll notice it took a lot of hard work. Seriously: the true and false papers took 7 revisions, and the keyword papers took 8 revisions to get the wording precisely right. This is because these changes are majorly backwards compatible with existing code.

s/keywords/predefined macros/g

There was a persistent fear in comments and in other places that these are, in fact, new “keywords”. Even the Wikipedia article describes the change as “alignas, alignof, bool, true, false, static_assert, thread_local become keywords”. This is mostly my fault for just being excited, so hopefully in writing this article many more individuals feel a lot less worried about their upcoming C code. The precise spelling of all of these new “keywords” is as Predefined Macros, defined by the compiler. This may feel like a distinction without a difference, but the distinction is what allows us to do this without breaking existing user code. Notably, the following is not an error:

#define foo 1

#define foo 0

#define __STDC_VERSION__ 0

int main () {

return foo + __STDC_VERSION__;

}

C allows you to redefine existing macros (or rather, implementations of C do). Most compilers emit a warning since it’s likely unintended for you to stomp all over existing macro space, but what this means is that it’s entirely backwards compatible for your code to continue to #define bool int or whatever horrific crimes you were committing in days gone by. Folks who were using a typedef instead, such as

typedef int bool;

May need to use #undef bool to get around the issue, or scope their typedef inside of an #if statement:

// Option 1

#ifndef bool

typedef int bool;

#endif

// Option 2

#undef bool

typedef int bool;

These techniques were already being employed in code that transitioned from C89 to C99 and had to deal with libraries prior to them that introduced #include <stdbool.h>, so this is thankfully not much of a break or an impediment to existing code. Note that we are defining bool here to be int like some kind of really horrible code gremlin, which is absolutely not what you should be doing if you don’t want to be wasting space or suffer issues with integer literals vs. true, blue _Bool-typed literals.

We also added special wording for true and falsein the preprocessor to make sure it’s handled properly in defined(...) expressions, to prevent any errors that might come about from a naïve keyword implementation of the predefined macros.

Hopefully, this helps put most of the concerns about backwards compatibility and breakage with respect to keywords rest! Jens Gustedt didn’t spill ink and climb the multi-year hill to put lesser versions of keywords into preprocessor as macros for everyone to lose their cool over finally being able to write thread_local!

typeof(...)

Document Number: N2927

This has been a long time coming. Some of the first mentions of typeof came in the C99 rationale, where they deemed that typeof was nice but they would like a little more time to settle out the semantics of it. (There were probably earlier ones, I just could not be bothered to go even further back in time.)

Fast forward 23 years later, and C will finally have one of the oldest and most existing-iest pieces of practice that has ever been part of the c Language.

Seriously, every compiler could do typeof since C89 with sizeof(...), since that was just equivalent to sizeof(typeof(...)). The bad part was that compilers hid that typeof(...) part from you, despite having the ability to compute the type of arbitrary expressions in order to get their type (and ultimately, their size). The only reason it took until Revision 5 is because we got caught up on Variably-Modified Types and Variable Length Array types, and execution-time vs. compile-time evaluation of the expression within the appropriate typeof(...).

This is also a rare case where because so many C implementations were shipping typeof, with that exact spelling and near-identical semantics, the Committee felt okay with taking the name typeof directly. This was not without spirited debate, but the overall consensus was that - for once - implementations held their ground and carried water over this implementation extension for this exact day, so it’s in.

While we were here, we also got to put a version of this directly applicable to the Linux Kernel in this called remove_quals(...). It works exactly like typeof(...) but it strips out qualifiers like _Atomic and const and friends. This feature came directly from observing people doing worse-than-unholy things in macros just to strip out qualifiers. Further in the thread and in tangential discussion on different places, the macro crimes committed to do UNQUALIFIED_TYPE(...) were some of the worst I’d ever had to see. (Even if I do think they’re amazingly brilliant.) Unfortunately, said macro crimes did not work across implementations (not even GCC and Clang agreed on how to choke on the preprocessing and deep-language sins being committed), and so it was deemed better to just pick up the existing practice and give the Linux folk a break.

C++ has decltype, Why Not decltype?

Because C does not have references. decltype has very C++-y deduction rules, which means that this code snippet changes its return type depending on whether the code is compiled in C mode versus C++ mode:

int value = 20;

#define GET_TARGET_VALUE (value)

inline decltype(GET_TARGET_VALUE) g () {

return GET_TARGET_VALUE;

}

int main () {

int r = g();

return r;

}

Macros are commonly used in C, and the general consensus is to always wrap the expansion of your macros in parentheses to stop any accidental precedence-mixing from operators. If any parentheses-wrapped expressions end up in a decltype(...), it goes from returning a normal T to instead returning a T&. This can cause QUITE a bit of grief if C used the same terminology as decltype(...) here.

So, the idea is that typeof(...) and remove_quals(...) - if they ever make it into C++ - will both not feature references. As a side note for C++ junkies, this means you can define a MOVE(...) macro to replace std::move that does not need to use the standard library’s type trait facilities. Because typeof deduces the non-reference type of what is put in, you can define it by using static_cast<typeof(__VA_ARGS__)&&>(__VA_ARGS__). Just something to think about if typeof ever gets proposed to C++ for the people who are doing truly absurd things to stop things like std::move from showing up in even their debug builds and massively increasing debug throughput with this.

There’s also some grumbling over in C++ land that it’s called remove_quals, so the final name might end up being typeof_unqual. I support that rename fully, and it was one of the alternative names to remove_quals, but a different group of C++ people were semi-grumbly over the name typeof_unqual (a longer time ago when I was first trying to name typeof and its no-qualifiers version). All in all, I don’t care how it’s spelled, just that I can spell it in some fashion. Pick something before C23 ships so I can put it in the next revision of the Working Draft, that’s all I ask!

char8_t (as a typedef) and Unicode Improvements!

Document Numbers: N2653 | N2828

This is something that will make quite a few Unicode folks happy, since it’s been a problem that’s been bothering them for quite some time now.

For those of you just shaking off the Standard Sleep from your eyes, C11 added a few new forms of string literal to make sure the type was encoded as one of an implementation-defined “UTF-8”, char16_t, or char32_t literal: u8"💣", u"💣", and U"💣", respectively. A paper I talk about in my earlier blog post mandated that the char16_t and char32_t literals actually produced UTF-16 and UTF-32 encoded strings (they didn’t have to, they could produce some inscrutable, implementation-defined encoding whose name you were not required to know when compiling your code). This updated all 3 string literals to be UTF-8, UTF-16, and UTF-32 respectively. Unfortunately, there was still one problem: while char16_t (a typedef for uint_least16_t) and char32_t (a typedef for uint_least32_t) were both mandated to be unsigned types, u8"🤡" had a type of const char[N]. What this meant is that calling a <ctypes.h> function like so:

isspace(u8"💣"[0])

is undefined behavior on specific implementations. In this case, this is a char value for a multi-unit UTF-8 string literal, which is larger than 127. It shows up as a negative value after promoted to int on implementations where char is a signed type, and that negative value is passed straight to the internals of the isspace function. What happens from there depends on your implementation, but on a few this is memory corruption and others it just grabs completely illegal data. Suffice to say, it has been a persistent problem that the thing that is meant to model UTF-8 characters produces an implementation-defined quantity of signed or unsigned for char.

This proposal fixed this situation by making the above code produce an unsigned char, so it will be the proper value when passed to the given functions. This only applies to the u8"💣" string literals: these are converted to arrays of const char8_t[N]. The char8_t typedef will live in the uchar.h header with the others, and it comes with 2 other functions to convert from the multibyte character locale encoding to UTF-8: mbrtoc8 and c8rtomb. I don’t recommend using these functions as a general rule because their design is fundamentally broken, but that’s a rant for another day (with a paper that also proposes the fix on the way for, hopefully, C23, but it hasn’t been accepted yet).

Of course, at this point I usually get asked this question by a lot of folk:

“Why not just mandate that char is an unsigned type?”

I just had to spend three paragraphs explaining how we spent 2 proposals, one with seven revisions and one with eight, and over 4+ years of work, just so we didn’t make bool a REAL keyword. How we deliberately made it macro soup instead, using preprocessor semantics and some special wording for true and false in the preprocessor to handle exactly this case, rather than just make it a blanket keyword. And now you want us - for a change that WOULD change the semantics of code (even if for the better) - to just snap our fingers and make char be an unsigned type for everybody?

You do the math on how this goes over with the C Community at large. 🙃

Much as I love fundamental improvements, I can neither predict nor confidently move in that direction, especially a break that produces silent runtime behavioral changes. You have to remember that this is the community that has largely ignored many advances in C11 and many fixes in C17 to stick with C99 and C89. They value old code quite high, and unless there’s demonstrable security failures or severe forewarning (on the order of decades), I cannot move to make changes of that magnitude or convince the Committee to make changes of that magnitude.

As a minor side fix, a smaller change that came along for the ride was that providing a Universal Character Sequence (the "\UFFFF" syntax in string literals) now does not allow you to specify a character that exists outside of Unicode. So, it has to be a well-formed character, not a Lone Surrogate, and under the 21-bit Unicode limit (e.g., the max is "\U0010FFFF").

Consistent, Warningless, and Intuitive Initialization with = {}

Document Number: N2900

Initialization, even in C, is harder than it should be. Many people have been burned by simply putting a semicolon after their struct and forgetting to properly initialize it (or a part of it) before use. And worse, as more security-focused individuals discovered and continue to battle with, = {0} and similar braced or designated initialization for automatic storage duration variable does not require that padding bits / bytes be initialized to 0. This has been a constant source of accidental data leakage in security-critical contexts, including the kernel.

The conventional wisdom to battle this has to always initialize your structures with memset. However, memset has a few well-known problems.

memset is Easy to Make Mistakes With

This is a human argument, so obviously more people than is acceptable will discard it by just banging the drum of C’s creators: “just be more careful”. But, whether we like it or not, we are not Gods but human beings. We seriously make mistakes, and many of us do not recognize it:

I lost the last week of February due to a bug I introduced in firmware attempting to zero out a structure:

memcpy(&spibuf, 0, sizeof(spibuf));Yeah, that’s copying from a

NULLpointer. Should’ve been:memset(&spibuf, 0, sizeof spibuf); // spibuf_t spibuf = {0}

When I quoted this as part of explaining why this change to the language was a necessary one, people still didn’t see the error that was made! This was with the fact that they explicitly knew they were looking for a bug:

Wait .. is there a difference if you use parentheses for sizeof…?

More folks in the thread (and in the original tweet from Scott) also needed a moment to see what the real problem was and how simple it was to fix. It is something that happens all too often: small mistakes can lead to large bugs, which can become exponentially large time sinks. A lot of resources and time are consumed, which could otherwise be devoted to features and improvements! But, before we go any further, let me be perfectly clear: neither of these people are bad developers. They are not doing something wrong, here. It’s that C has very specifically created a set of conditions where, in attempting to follow best practices, the developers made easy and harmless mistakes that can result in some very nasty bugs.

This is why memset is not ideal. Yes, it has the security properties we would like here (initializing padding bits to 0). But decades of people making exactly these mistakes and being human enough not to catch it means that we end up with this kind of problem a lot. Worse, memset has one more serious non-human, technical drawback that degrades its usefulness as a truly cross-platform solution to initialization.

All-Bits-Zero is not Always Correct

This is best illustrated by Kate’s maliciously conforming TenDRA compiler, which allows you to do things like screw around with the actual, physical representation of elements:

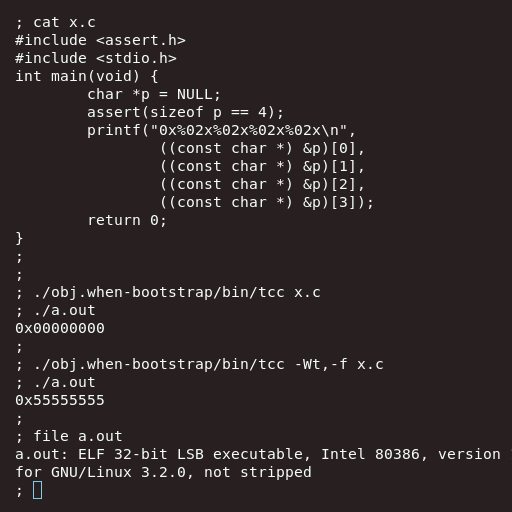

… And that brings us to the TenDRA compiler, which can use 0x55555555 for its null pointer representation, if you like.

So here’s an implementation of C compiling to x86 where the value of NULL is 0, but the underlying byte-by-byte representation is 0x55555555.

Now, I say “malicious”, but as evidenced by the tweet from Scott earlier we know that there exist implementations where writing to all-bits-zero doesn’t necessarily produce a failure or fault. This is because there are many tiny devices and embedded scenarios where literal all-bits-zero points to a real address used for things. For example, all-bits-zero tends to be a semi-popular location to put the bootloader, and it’s where a lot of devices will write to while the actual bit-for-bit representation of NULL will instead be something like 0xFFFFFFFF.

All this to say, given a structure that looks like this:

struct meow {

int nya;

char purr;

struct meow* known_strays;

};

Doing this:

struct meow m;

memset(&m, 0, sizeof(m));

results in a by-the-bit representation on a 32-bit Digital Signal Processor that looks something like:

| size | 4 bytes | 1 byte | 3 bytes | 4 bytes |

| field | nya |

purr |

(padding) | known_strays |

| bit-pattern | 0x00000000 |

0x00 |

0x000000 |

0x00000000 |

| value | int: 0 |

char: 0 |

(padding): 0s | pointer-to-0 |

But this can be wrong for the architecture, since the NULL pointer that you actually want may be 0x55555555 (e.g., on TenDRA). Or, more realistically, it can look like the INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE or similar construct, where the NULL pointer for the machine is actually spelled 0xFFFFFFFF. This is where = {} pays off big: it mandates that it initializes to the actual representation of the NULL pointer in the wording. So, you get the correct NULL constant by doing:

struct meow m = {};

Which yields the the “true” representation:

| size | 4 bytes | 1 byte | 3 bytes | 4 bytes |

| field | nya |

purr |

(padding) | known_strays |

| bit-pattern | 0x00000000 |

0x00 |

0x000000 |

0xFFFFFFFF |

| value | int: 0 |

char: 0 |

(padding): 0s | pointer-to-NULL |

It’s shorter, sweeter, more correct, and less hassle. It makes sure the compiler does its job correctly. It’s a small thing, but it’s a HUGE win for correctness here and a BIG win for security-focused applications, which need the padding bits to not leak old data stuck in the gaps of the structure. Plus, it’s shorter than all the other forms of initialization and easier to write with no chance of screwing it up!

Simple thing: big improvements, all coming to C23.

unreachable() Macro for Optimization and Code Improvement

Document Number: N2826

This paper was accepted in its macro form for C23. It provides standard access to a common optimization pattern that exists as a builtin in GCC and Clang-alike compilers (__builtin_unreachable()) and MSVC-like compilers (__assume(false)). The way it works is that it deliberately triggers undefined behavior when used. Used in conjunction with ternaries or other conditional structures, it can be used to weed out specific branches and inform the optimizer of case that either cannot happen or should not happen, providing performance gains for suitable optimizers. Here’s an example lifted from some cppreference, C-ified to show it off:

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stddef.h> // size_t and not has unreachable()

typedef struct color { uint8_t r, g, b, a; } color;

// color_vec that works over pointer-to-array

#define VEC_TYPE color

#define VEC_NAME color_vec

#include <vec.h>

void generate_texture(color** p_texture, size_t square_wh) {

switch (square_wh) {

case 128: [[fallthrough]];

case 256: [[fallthrough]];

case 512: /* ... */

color_vec_clear(p_texture);

color_vec_resize_init(p_texture,

square_wh * square_wh,

(color){0, 0, 0, 0});

break;

default:

unreachable();

}

}

In this case, we have a pre-defined set of values that we do work with. The texture value should only be one of those 3 values, ever. We don’t want to spend the time accounting for other cases, or providing backup code here: it literally cannot happen (due to us performing some validation before ever calling this function). So, we mark the default switch case as being completely unreachable(). This lets the compiler elide code that has anything to do with it not being one of those 3 values. This is a pretty simple example, but we can do even better. For example, let’s consider a tight audio processing loop, where we want the compiler to give us optimal code after making some assumptions about what’s going on.

Audio Limiter

Here’s a basic limiter, that hard-clamps the value of a single sample (a single unit of audio data) to the typical minimum and maximum we desire:

#include <stddef.h>

static float clamp(float v, float lo, float hi) {

return (v < lo) ? lo : ((hi < v) ? hi : v);

}

extern void limiter(float* data, size_t size) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < size; ++i) {

data[i] = clamp(data[i], -1.0f, 1.0f);

}

}

Let’s take a look at the assembly that comes out on the other side (gcc -std=c2x -O3):

limiter:

mov rcx, rdi

test rsi, rsi

je .L1

lea rax, [rsi-1]

cmp rax, 2

jbe .L11

mov rdx, rsi

movss xmm5, DWORD PTR .LC0[rip]

mov rax, rdi

pcmpeqd xmm6, xmm6

shr rdx, 2

movss xmm4, DWORD PTR .LC1[rip]

sal rdx, 4

shufps xmm5, xmm5, 0

add rdx, rdi

shufps xmm4, xmm4, 0

.L4:

movups xmm1, XMMWORD PTR [rax]

movaps xmm0, xmm5

add rax, 16

movaps xmm3, xmm1

cmpltps xmm3, xmm5

movaps xmm2, xmm3

andps xmm0, xmm3

andnps xmm2, xmm4

orps xmm2, xmm0

movaps xmm0, xmm4

cmpltps xmm0, xmm1

por xmm0, xmm3

pxor xmm0, xmm6

andps xmm1, xmm0

andnps xmm0, xmm2

orps xmm0, xmm1

movups XMMWORD PTR [rax-16], xmm0

cmp rdx, rax

jne .L4

test sil, 3

je .L1

mov rax, rsi

and rax, -4

.L3:

sub rsi, rax

cmp rsi, 1

je .L6

movq xmm0, QWORD PTR .LC4[rip]

lea rdx, [rcx+rax*4]

movq xmm1, QWORD PTR .LC5[rip]

movq xmm2, QWORD PTR [rdx]

movaps xmm4, xmm2

cmpltps xmm4, xmm0

movaps xmm3, xmm4

andps xmm0, xmm4

andnps xmm3, xmm1

cmpltps xmm1, xmm2

orps xmm3, xmm0

movaps xmm0, xmm1

movq xmm1, QWORD PTR .LC6[rip]

por xmm0, xmm4

pxor xmm0, xmm1

andps xmm2, xmm0

andnps xmm0, xmm3

orps xmm0, xmm2

movlps QWORD PTR [rdx], xmm0

test sil, 1

je .L1

and rsi, -2

add rax, rsi

.L6:

lea rax, [rcx+rax*4]

movss xmm1, DWORD PTR .LC0[rip]

movss xmm0, DWORD PTR [rax]

comiss xmm1, xmm0

jbe .L27

movaps xmm0, xmm1

movss DWORD PTR [rax], xmm0

ret

.L27:

movss xmm1, DWORD PTR .LC1[rip]

minss xmm1, xmm0

movaps xmm0, xmm1

movss DWORD PTR [rax], xmm0

ret

.L1:

ret

.L11:

xor eax, eax

jmp .L3

.LC4:

.long -1082130432

.long -1082130432

.LC5:

.long 1065353216

.long 1065353216

.LC6:

.long -1

.long -1

This will be our baseline. It’s about 97 lines of cleaned-up, prettified assembly. The assembly spends a lot of time carefully picking at the pointers and pulling out values to be checked and used. (NOTE: in a previous version of the article, I messed up the clamp(...) definition. That changed the listing to be 97 lines long as shown here, rather than the original 61, but the second remains largely unchanged.)

What assumptions can we make that might improve our situation?

Well, we generally know that we’re not processing NaNs in our audio flow. All our math is well-scoped and well-defined (what does a “Not a Number” sample sound like in the first place??). We know we typically get nicely-sized chunks to process from the audio stream, too: generally, we never get single samples, but we get sample streams that are a multiples of a specific value. Some powers of 2 are usually good values (32, 64, 128, though 256 might be pushing it), so let’s say that it’s got to be a multiple of 32. Let’s add some of these annotations to the code using the new unreachable() that C23 has into a new spicy_limiter function. We will mock up unreachable() on a Clang/GCC-compatible-alike compiler:

#include <stddef.h>

#include <math.h>

// C23 mockup for Clang/GCC-like compilers

#define unreachable() __builtin_unreachable()

static float clamp(float v, float lo, float hi) {

return (v < lo) ? lo : ((hi < v) ? hi : v);

}

extern void spicy_limiter(float* data, size_t size) {

if (size < 1 || (size % 32) != 0) {

unreachable();

}

for (size_t i = 0; i < size; ++i) {

if (!isfinite(data[i])) {

unreachable();

}

data[i] = clamp(data[i], -1.0f, 1.0f);

}

}

“EWWW, gross, that’s SO MUCH more code! AND it has branches, it MUST be terrible!” I had that thought too, looking at this code. And yet, with the same compiler and same flags…

spicy_limiter:

movss xmm1, DWORD PTR .LC0[rip]

movss xmm2, DWORD PTR .LC1[rip]

xor eax, eax

jmp .L3

.L9:

movaps xmm3, xmm2

minss xmm3, xmm0

movaps xmm0, xmm3

movss DWORD PTR [rdi+rax*4], xmm0

add rax, 1

cmp rsi, rax

je .L8

.L3:

movss xmm0, DWORD PTR [rdi+rax*4]

comiss xmm1, xmm0

jbe .L9

movaps xmm0, xmm1

movss DWORD PTR [rdi+rax*4], xmm0

add rax, 1

cmp rsi, rax

jne .L3

.L8:

ret

.LC0:

.long -1082130432

.LC1:

.long 1065353216

…. Daaaamn, that’s way better. From 61 lines for the full assembly to 28! And we are getting all the good scalar intrstructions we want, too (movaps, comiss, movss, and minss)! It even manages to cut the clamp call out, since it can assume the values are safe to pass through the registers and there won’t be any signaling NaNs. That is a S P I C Y limiter, indeed! We could probably get even better, but this is just illustrative of how much better we can get from the code.

A lot of people get scared when they see “Undefined Behavior”, but this is one of the first times we’re putting Undefined Behavior - and its subsequent optimization potential - in your hands as the end-user. This means rather than praying that you don’t run afoul or something, or doing 1/0 in a branch to deliberately trigger UB in that branch and hope the compiler takes a bushwhacker to the code to clean it up, you can clearly expression your semantic desire and let the compiler do what it does best. Working together, rather than against!

Plus, in debug/tracing modes, you can rig up unreachable() to instead do actual checking and be a loud, noisy crash. Performance when you want it, safety when you don’t, and C23 puts that power directly in your hands because we trust you do know what you’re doing. (And if you don’t, then you shouldn’t be using it, so please UB responsibly and don’t heavy mistakes with it.) Speaking of debug and tracing modes…

Make the assert() Macro User-Friendly for C

Document Number: N2829

It’s a simple fix, and frankly one that’s extremely overdue. assert(cond) has long been a gigantic pain in most people’s backsides because of how macros parse their arguments. Whenever someone had a stray comma in a struct definition without an enclosing pair of parentheses, assert(cond) would lose its shit entirely. The paper makes assert use a variadic definition of assert(...), which allows passing multiple arguments to the function and sticthing them together.

We had to be careful with the specification here because we wanted to ensure we were not accidentally triggering the difference between too-many-arguments and the comma operator. So, the specification for assert now says it passes the condition to some magical, internal, implementation-defined function to prove that the expression is truly meant to fold down into 1 argument. Likely, this can be gotten away with by definition an argument taking a single bool (or similar) argument and packing it inside of a sizeof, such that it might look a little like sizeof(__mandate_one_argument_only(__VA_ARGS__)) before getting to the meat of the assert call.

This is a pretty nice usability improvement, and I’m glad Peter Sommerlad stuck this one out for C! (The Committee almost got lost in the weeds for trying to decide whether it wanted to delay this fix and go straight to the heart of the issue, which is that Macros Suck And We Need Better Preprocessor Functions To Make It Better. We did not vote to do this, but it’s an ever-looming crisis we experience at least once every 2 Standards Meetings and every time something interacting with the preprocessor comes along, for sure.)

This gets us to one of the last changes I’ll talk about in this blog post.

K&R Function Declaration AND Definitions are 🪦🪦!

Document Number: N2432 | N2841

K&R Declarations and Definitions have been in existence since before C was really an official ISO Standard (or ANSI Standard) language. They went into C89 deprecated, and Ritchie himself stated in his own written work available at his website that they borrowed the new “functions with protoypes” (functions that have types and arguments in declaration and definnition) from C++:

X3J11 introduced only one genuinely important change to the language itself: it incorporated the types of formal arguments in the type signature of a function, using syntax borrowed from C++ [Stroustrup 86].

Indeed, reading The C Programming Language, 2nd Edition, reaffirms how important this was:

Function declarators with parameter prototypes are, by far, the most important language change introduced by the ANSI standard. They offer an advantage over the “old-style” declarators of the first edition by providing error-detection and coercion of arguments across function calls, but at a cost: turmoil and confusion during their introduction, and the necessity of accomodating both forms. Some syntactic ugliness was required for the sake of compatibility, namely void as an explicit marker of new-style functions without parameters.

At the time, they felt they could not remove the K&R “old-style” definitions. It had not been deprecated long enough, and the new syntax had not been around for long enough (it hadn’t been around at all, in fact). So, they rolled it into C89 deprecated, and explicitly discouraged its use for some 33+ years. It’s been deprecated longer than I’ve been alive (sorry to those of you reading this and feeling old)! But, well, since it’s been deprecated for so damn long, the Committee finally felt that it was time to retire the unsafe K&R declarations and definitions.

It’s no secret that I think K&R declarations are unsafe, error-prone, and dangerous. So I was happy that in the first revision of the C Standard that I joined the Committee, we were going to get rid of it and make void foo(); mean that it was an argument taking 0 parameters, adjusting the syntax back to what Kernighan and Ritchie had yearned for in their language originally with prototypes. Unfortunately, it’s not all Happy-Happy Sing-Along Songs. We removed some functionality when we did this, particularly ~3 different use cases. One was related to the declaration, and the other was related to definitions.

The Usefulness of void f();

It was not explicitly sanctioned, but one of the uses of having a definition that can take any number of parameters was that you could hook it up to other kinds of procedures that existed outside of the auspice of the C language. In C code before C23, you could write:

#include <time.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

extern int compute_with_see_sharpe ();

int main () {

time_t time_val = {0};

return compute_with_see_sharpe(&time_val, 2.0f, true, "important");

}

Even if it was deprecated to use K&R declarations, that function still took all those arguments (after promotion to double and int took place for each argument). One could then, as long as they set up their linker and runtime loader correctly, hook this code up to a .NET or Mono function call from the C# language. C# could compute that value, and return an integer just fine:

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

namespace C_Interop {

[DllExport("compute_with_see_sharpe"), CallingConvention = CallingConvention.Cdecl]

public static int compute_with_see_sharpe(

IntPtr TimeValPtr,

double ScalePromoted,

bool NameAdjusted,

MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.LPStr)] string lpString) {

// Commit crimes

return 0;

}

}

This alone is not enough of a justification, of course. After all, you can perfectly replicate the signature of compute_with_see_sharpe in C. What’s more interesting is that this was used to communciate with more complicated languages like assembly or to Javascript, where even the # of arguments and other things could change dynamically. This meant that there was no matching prototype to use, and the function name was just a stand-in for a symbol that could be called with whatever # and types of arguments.

The fix for declarations (and definitions in C that would like to utilize a similar power) is the paper N2919, by Alex Gilding. She proposes removing the restriction on ... variable-argument declarations and definitions, allowing them to have no required preceding argument. This can then be used to capture the same conceptual and semantic details that the K&R declaration of int compute_with_see_sharpe(); did, by just doing a mechanical change:

#include <time.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

extern int compute_with_see_sharpe (...);

int main () {

time_t time_val = {0};

return compute_with_see_sharpe(&time_val, 2.0f, true, "important");

}

The argument promotion rules for ... functions and K&R functions are identical, here, so semantically this is the same code. It may run afoul of some ABI requirements on specific platforms where the convention for passing arguments to a variable-arguments function is different from K&R. In those cases, implementations may need to provide implementation-specific attributes to retain the exact register and stack-based calling convention so that it communicates properly with the outside:

#include <time.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

// Suggest the compiler uses old K&R argument calling convention

[[abi::kandr]] extern int compute_with_see_sharpe (...);

int main () {

time_t time_val = {0};

return compute_with_see_sharpe(&time_val, 2.0f, true, "important");

}

Note: [[abi::kandr]] is not a real attribute. It’s not in the standard. It’s just a not-so-subtle suggestion to your implementation to implement an attribute with a similar name. Give it a more specific name, like [[arm7va::kandr]] or something, please!

Unfortunately, because calling convention and Application Binary Interface (ABI) lay outside of the standard, there’s no cross-platform, standard solution we can provide. But, the attribute solution is a pretty good one and for implementations where it matters, we encourage users to prompt their implementers to provide such functionality. It was already a silent contract between the implementation and the end-user where arguments were stored, and keeping that code working means implementers should once again look into the quality of their implementations to support users making the transition. This is, of course, only if N2919 is accepted, but it’s the best we can do. Which leads to a different, but smaller, problem…

K&R Definitions and VLA/VMT/Static-Extent Parameters

One of the things that’s terrible about both C and C++ is that things have to be declared in a lexical order before they are used. What this means is that you cannot write something like this:

unsigned char* sized_memcpy(

unsigned char dest[static n], // "at least n bytes"

const unsigned char src[static n], // "at least n bytes"

size_t n) {

// ...

// super fast speed here

return NULL;

}

C will error upon the first static n, because n isn’t declared yet. Come K&R definitions, which allow you to commit wonderful little crimes:

unsigned char* sized_memcpy(dest, src, n)

size_t n; // !! moved up before in the parameter definition-list!

unsigned char dest[static n]; // "at least n bytes"

const unsigned char src[static n]; // "at least n bytes"

{

// ...

// super fast speed here

return NULL;

}

This parses and works in Standard C. It allows you to separate the parameter order from what it declares. The only problem with this syntax is that it’s not usable as a declaration. It has to be paired with the K&R declaration syntax when separating defintion and declaration, which makes it error prone. Unfortunately, even if that is the case, removing K&R declarations and definitions means we get rid of the use case where size parameters come after pointer parameters that you want to put size information inside.

Ultimately, the cost-benefit of keeping this is minimal. K&R declarations cannot provide call-site checking because the declaration would look like this in all versions of C that support K&R:

unsigned char* sized_memcpy();

This means that any code trying to call this function would not get the benefit of a VLA parameter, Variably-Modified Type parameter, or static-extent array parameter declarations in the first place (no information on how to check at the call site). There was a proposal to fix this - N2780 by Martin Uecker - that allowed you to “forward declare” parameters. This would solve the small hole left by K&R definitions, allowing you to “forward declare” parameters in the argument list and then use them “for real” later:

unsigned char* sized_memcpy(

size_t n; // note the semi-colon ";"

unsigned char dest[static n], // Position 0

const unsigned char src[static n], // Position 1

size_t n // Position 2, the "real" declaration

) {

// ...

// super fast speed here

return NULL;

}

I will be honest, even without all the comments, the forward declaration syntax is not very appealing:

unsigned char* sized_memcpy(size_t n;

unsigned char dest[static n],

const unsigned char src[static n],

size_t n);

It uses a very visually similar separator - the ; - to separate the forward parameter declaration list from the normal parameter declaration list. When I presented this to a few people they either missed the semicolon entirely, were confused why “two arguments had the same name”, and similar issues. This could simply be a teaching issue, where VLA parameters and static-based parameters have not been used and advocated enough in common codebase and literature that it has caught on. Still, I was in favor of the paper because it provided a material solution to an existing problem and it had already been implemented in GCC and a few other places. It technically met the criteria for having multiple existing, long-standing implementations, but feelings about it were not great. So, ultimately, the paper did not go anywhere.

I asked the Committee to take a vote on whether or not they would not mind having forward parsing for function declarators. That is, could we just simply make:

unsigned char* sized_memcpy(unsigned char dest[static n],

const unsigned char src[static n],

size_t n);

work, by allowing identifiers declared later in the parameter list to be referenced earlier? There was EXTREMELY WEAK consensus (BARELY consensus) to maybe explore that idea. I have no intention of writing a proposal to do it because the consensus was so pitifully weak, and there are a lot of people who would be concerend that such forward-parsing might complicate their implementations to much. But, it would be an elegant solution that does not require extra user markup. It could open the Pandora’s Box on the subject of “well, if we can do it here, why can’t we do it everywhere?”, and then people start losing their minds. All in all, anyone reading this blog post should consider this an open problem, and should be going into their implementations / talking to their implementers about how to make something like this work. Try a few things out, come up with new syntax to make this case work. Maybe something you come up with will stick! If it does, let me know as soon as you can.

This effectively leaves 1 use case for K&R definitions out in the cold for C23. This one doesn’t cause me too much consternation for many of the reasons I stated above, but it’s not exactly the world’s worst problem. Maybe the loss of this functionality will drive more users and implementations to embrace the GCC forward parameter declarations and ship it in more code. That might indicate to WG14 this extension is worth the standardization time, but for now the Committee did not vote to take it forward into the C Standard.

This leaves one last compatibility issue from K&R declarations, and it has to due with function pointer storage.

Incomplete “K&R” Function Pointers

Consider this tiny li’l program from a C programmer from Reddit:

typedef void (*invoker)(void (**)(), int);

void do_something(invoker *proc, int x) { (*proc)(proc, x); }

invoker my_invoker[1] = {&do_something};

This code is relying on the fact that void (**)() is effectively an incomplete function pointer. It can be used to call any kind of function in the language, since it will complete with its given argument types and then call the function. Unfortunately, this code isn’t completely unaffected. If N2919 passes, then the plan is that these function pointers will be swapped with void(**)(...) function pointers instead. You will have to dereference the double-indirected function pointer, and then perform a cast to get to the right function type before calling. It is a little more effort than before, but ultimately covers the use case for that particular style of programming. Of course, the most notable thing about K&R declarations of all is…

K&R Declarations Will Never Actually Die 🧟♀️

While many coding guidelines can stop providing guidance and simply say “they are not in the standard anymore”, the chances of GCC or Clang actually removing K&R declarations is close to 0%. They would need to remove the -std=c89 flag, and every flag from then until -std=c23. It’s never going to happen, at least not at any point in my lifetime. C will turn 100 years old and people will still be compiling and using K&R functions, but after 33+ years of deprecation?

It should not be the standard’s burden to carry it, and implementations should have the freedom to move on.

If 30 years is not enough advance notice to move on from a construct that its creators have expressly stated was an inferior idea, then we should simply stop pretending that C can become a better version of itself. We should stop trying to improve the memory model, stop trying to fix atomics, stop trying to get rid of Undefined Behavior, declare this a done project, and head out the door to work on better, not-dead things. But, given the volume of proposals we get and the enthusiasm we receive when things do (or do not) end up in C23, I highly doubt people are done with C as a language and ready to declare it “done”. It’s probably a lot closer than many other languages to being there (modulo our severe problems with Undefined Behavior), but if it is not dead than it will need maintenance and improvement. Deprecation very clearly states that one day it will be considered for removal. As a personal note, I feel like once N2919 goes into C23 we will have absolutely covered the 97% of valid use cases. The remaining 3% regarding parameter ordering should be solved in a more intrinsic way, and if neither the community nor implementers feel like parameter forward declarations are the solution, than we need better ones.

Compiler implementations may never move on thanks to needing to support -std=c17 for the next 50 years, but we as human beings definitely should. Even human languages change based on the people speaking it and the things happening around us; programming languages are no different. Which, speaking of making changes based on what’s going on around us…

16-bit ptrdiff_t. Again!

Document Number: N2808

This is more of a pedantic change than anything. Most embedded devices that had 16-bit pointers were just running around with 16-bit ptrdiff_t values anyways, meaning you could not get the FULL difference between an object larger than half the size of main memory without overflowing into the negatives. The C standard originally required that ptrdiff_t be 17 bits as a minimum (to allow for a sign plus representing the full required 16 bit-minimum mandated for size_t). But people just shrugged their shoulders and deliberately broke away from the Standard to work on their machines. In short, folks never really cared that we had a theoretically correct and beautiful 16-bit size_t and 17-bit ptrdiff_t value: they just went with both being 16 bits and said to hell with any kind of object/array larger than half the size of main memory.

It’s good to reflect reality rather than try to insist on a theoretical purity. I’m sure someone will have an existential crisis that they can’t take up more than half of their embedded chip’s memory with a single allocation, but that person is just going to have to figure out a coping mechanism.

Separating Variably-Modified Types from Variable Length Arrays

Document Number: N2778

This was an interesting paper. I did not know much about Variably-Modified Types (VMTs) versus Variable Length Arrays (VLAs), or what the differences between the two were. It turns out that Variably-Modified Types are actually really cool, and can go a long way to making handling arrays and allocations a lot better in C. They still fail in very specific ways that make me think we still need more in the C Language to fix our true issues with pointers and sizes, but until then in C23 Variably-Modified Types will have to do!

For folks who were like me, Variably-Modified Types are types which, like VLAs, are dependent on some runtime information. But, unlike VLAs, they do not do any of the allocation and its associated pitfalls: it just represents a type that keeps its own size around (in bytes). The way they do this is by, essentially, taking the syntax space of “pointer to VLA” and similar. Here’s a brief example, showing a VMT and its resilience against having the variable which dictates its size changed out from underneath it:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int n = 2;

int m = 3;

int (*p)[n][m] = malloc(sizeof * p);

printf("%zu\n", sizeof(*p));

printf("\n");

m = 4;

printf("%zu\n", sizeof(*p));

printf("\n");

n = 50;

printf("%zu\n", sizeof(*p));

printf("\n");

free(p);

}

This program will print:

24

24

24

which means that we’ve finally found something that, even if we change the variables associated with the array, it does not change the actual size of the array. We get a good 24 / sizeof(int) (6) integer elements to work with, and sizeof(*p) reports the correct size! This is a huge boon for writing correct numerical code while at the same time avoiding the pain of VLAs and their issues with poor choice of syntax and compiler-hidden allocation. You can use alloca(...) or malloc(...) (or similar) and then simply create the right VMT to keep the size around! With this being in mandated, standard C and separated from VLAs, you can now depend on the above code working in C23 and above even if the __STDC_NO_VLA__ predefined macro is defined to 1.

Not all Rainbows and Sunshine

As with all things in C, there’s a big ol’ drawback. Let’s get the same VLA as before, but let’s pass it and its parameters to a function…

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

void print_array_size(int n, int m, int (*p)[n][m]) {

printf("%zu\n", sizeof(*p));

}

int main() {

int n = 2;

int m = 3;

int (*p)[n][m] = malloc(sizeof * p);

printf("%zu\n", sizeof(*p));

print_array_size(n, m, p);

printf("\n");

m = 4;

printf("%zu\n", sizeof(*p));

print_array_size(n, m, p);

printf("\n");

n = 50;

printf("%zu\n", sizeof(*p));

print_array_size(n, m, p);

printf("\n");

free(p);

}

Unfortunately for us, this program prints out:

24

24

24

32

24

800

The original variable declaration and cast works, but here the information that could help us out is dropped on the floor. The compiler has to form a new VMT value for each function call, so any size information stored in that original VMT that we’re using from main gets completely lost. This is not much better than the current situation with normal c arrays, where even looking at that array funny decays it to a pointer and drops all size information on the ground.

VMTs are still useful when used locally within a function, but as a means of actual transportation of information across functions and structures they continue to leave a lot to be desired. Walter Bright’s criticism of C continues to be relevant to this day, and we continue to have bugs where developers misinterpret or otherwise get the size wrong. I am grateful for having VMTs in the language in-general now, but it does make me fear that another 40 years of subtle used-the-wrong-integer-with-my-VMT bugs may once more leave us without the solution we need.

There Is More…

But this article has gone on long enough. Other things not mentioned here are:

- (N2775) Literal Suffixes for

_BitInt(N)types are in:0x10wbreturns in a signed_BitInt(5)(the smallest possible integer type that can represent the integer literal). - (N2701)

@,$, and`(backtick) are added to the source character set: Doxygen docs and Markdown snippets in comments are far more portable than ever before (not that it necessarily matters in a material, real sense). - (N2764)

[[_Noreturn]]is a real attribute now, giving everyone access to a way to say their function will never return. - (N2840)

call_onceis now mandatory across implementations. This is good and it was annoying it could be thrown out on specific implementations.

Some things I do not have enough experience with (like the tons of Decimal Floating Point changes we make every meeting, many of them small and just trying to clean it up so that it’s ready to ship in C23), or things that I am not sure would be considered blockbuster features. That does not mean we are not continuing to work on it. There is a large swath of things which may still make C23, such as Endianess Macros, Modern Bit Utilities, Unicode printf modifiers for printing things, Comma Omission and Deletion for Variadic Macros (e.g. the __VA_OPT__ fix from C++), memset_explicit for safety and security purposes, Unicode functions to convert inbetween all of the Unicode and wide/narrow locale encodings, Enumeration fixes (underlying type and larger-than-int-enumerations), and much more.

Some things were also defeated this past meeting, meaning we won’t see them for C23. Some have a chance beyond C23, others are probably close to dead.

- (N2896)

#onceand#once YOUR_GUARD_ID_HERE, to reduce include guard spam, was narrowly voted down and thus likely won’t come back without some serious modifications, adjustments, or a massive wave of user outcry to force their implementers to implement it. This one is a bitter pill for me to swallow. I would have absolutely loved even the second form, but… alas. - (N2895, N2892)

defer, Lambdas, and similar were voted down, but still have consensus to proceed for a timeline beyond/after C23. I’ve personally volunteered to direct and maybe even steer the effort for Lambdas.defermight come along for the ride since it’s basically in the same vein when it comes to what variables are available fordefer. Spoiler: we’re going to be pursuing barebones, simpledeferthat is block-scoped (to the nearest braces, or conditional/etc. if the braces are omitted). This is mostly to save us from making the same design mistake Go did, where they have adeferthat may dynamically allocate (?! Jesus Christ!) or other complete nonsense. - (N2859)

break break;,break continue;,break break continue;, and similar iterations of a way to get out of multiple switch/loop statements was carefully put on ice. The proposal author probably got the same sense I did: if a vote was taken, it likely might not have passed, especially for C23. So, they elected not to and will come back with a paper in the far future. Even if I’d prefer a labeled loop, that was the most politically savvy decisions I’ve seen out of someone in a Committee. By not having a vote, the paper is not officially rejected: they can come back with a proposal later on with no recorded elbow drop slaying the feature forever. Very smart! - (N2917)

constexpr- an extremely watered down version compared to C++ that is super simple and deliberately intended not to be much more than updated ways of handling constants in C - did not die. There is strong support to work on it, albeit it might not make C23. Which is perfectly okay, as long as it stays alive!

That’s the full status update. Hopefully things will keep going well in the C Meetings and we’ll get some of the last juicy library and language bits in for C23 for you all!

Until next time. 💚

P.S.: titties. (If you’re reading this, Kate, it worked!)

Title photo by Roman Odintsov, from Pexels.