Last time we talked about encodings, we went in with a C++-like design where we proved that so long as you implement the required operations on a single encoding type, you can go between any two encodings on the planet. This meant you didn’t need to specifically write an e.g. SHIFT-JIS-to-UTF-8 or UTF-EBCDIC-to-Big5-HKSCS pairwise function, it Just Worked™ as long as you had some common pivot between functions. But, it involved a fair amount of template shenanigans and a bunch of things that, quite frankly, do not exist in C.

Can we do the same in C, nicely?

Well, dear reader, it’s time we found out! Is it possible to make an interface that can do the same as C++, in C? Can we express the ability to go from one arbitrary encoding to another arbitrary encoding? And, because we’re talking about C, can it be made to be fast?

In totality, we will be looking at the designs and performance of:

- simdutf

- iconv (patched vcpkg version, search “libiconv”)

- boost.text (proposed for Boost, in limbo…?)

- utf8cpp

- ICU (plain libicu & friends, and presumably not the newly released ICU4X, or ICU4C/ICU4J)

- encoding_rs through it’s encoding_c binding library

- the Windows API, both

MultiByteToWideCharandWideCharToMultiByte - ztd.text, the initial C++ version of this library leading P1629

We will not only be comparing API design/behavior, but also the speed with benchmarks to show whether or not the usage of the design we come up with will be workable. After all, performance is part of correctness measurements. No use running an algorithm that’s perfect if it will only compute the answer by the Heat Death of the Universe, right? So, with all of that in mind, let’s start by trying to craft a C API that can cover all of the concerns we need to cover. In order to do that without making a bunch of mistakes or repeated bad ideas from the last five decades, we’ll be looking at all the above mentioned libraries and how they handle things.

Enumerating the Needs

At the outset, this is a pretty high-level view of what we are going for:

- know how much data was read from an input string, even in the case of failure;

- know how much data was written to an output, even in the case of failure;

- get an indicative classification of the error that occurred; and,

- control the behavior of what happens with the input/output that happens when a source does not have proper data within it.

There will also be sub-concerns that fit into the above but are noteworthy enough to call out on their own:

- the code can be/will be fast;

- the code can handle all valid input values; and,

- the code is useful for other higher level operations that are not strictly about encoding/decoding/transcoding stuff (validation, counting, etc.).

With all this in mind, we can start evaluating APIs. To help us, we’ll create the skeleton of a table we’re going to use:

| Feature Set 👇 vs. Library 👉 | ICU | libiconv | simdutf | encoding_rs/encoding_c | ztd.text |

| Handles Legacy Encodings | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Handles UTF Encodings | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Bounded and Safe Conversion API | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Assumed Valid Conversion API | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Unbounded Conversion API | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Counting API | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Validation API | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Extensible to (Runtime) User Encodings | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Bulk Conversions | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Single Conversions | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Custom Error Handling | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Updates Input Range (How Much Read™) | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Updates Output Range (How Much Written™) | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Feature Set 👇 vs. Library 👉 | boost.text | utf8cpp | Standard C | Standard C++ | Windows API |

| Handles Legacy Encodings | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Handles UTF Encodings | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Bounded and Safe Conversion API | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Assumed Valid Conversion API | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Unbounded Conversion API | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Counting API | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Validation API | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Extensible to (Runtime) User Encodings | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Bulk Conversions | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Single Conversions | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Custom Error Handling | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Updates Input Range (How Much Read™) | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

| Updates Output Range (How Much Written™) | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ | ❓ |

The “❓” just means we haven’t evaluated it / do not know what we’ll get. Before evaluating the performance, we’re going to go through every library listed here (for the most part; one of the libraries is mine (ztd.text) so I’m just going to brush over it briefly since I already wrote a big blog post about it and thoroughly documented all of its components) and talk about the salient points of each library’s API design. There will be praise for certain parts and criticism for others. Some of these APIs will be old; not that it matters, because many are still in use and considered fundamental. Let’s talk about what the feature sets mean:

Handles Legacy Encodings

This is a pretty obvious feature: whether or not you can process at least some (not all) legacy encodings. Typical legacy encodings are things like Latin-1, EUC-KR, Big5-HKSCS, Shift-JIS, and similar. Usually this comes down to a library trying (and failing) to handle things, or just not bothering with them at all and refusing to provide any structure for such legacy encodings.

Handles UTF Encodings

What it says on the tin: the library can convert UTF-8, UTF-16, and/or UTF-32, generally between one another but sometimes to outside encodings. Nominally, you would believe this is table-stakes to even be discussed here but believe it or not some people believe that not all Unicode conversions be fully supported, so it has to become a row in our feature table. We do not count specifically converting to UTF-16 Little Endian, or UTF-32 Big Endian, or what have you: this can be accomplished by doing an UTF-N conversion and then immediately doing byte swaps on the output code units of the conversion.

Safe Conversion API

Safe conversion APIs are evaluated on their ability to have a well-bounded input range and a well-bounded output range that will not start writing or reading off into space when used. This includes things like having a size go with your output pointer (or a “limit” pointer to know where to stop), and avoiding the use of C-style strings on input (which is bad because it limits what can be put into the function before it is forced to stop due to null termination semantics). Note that all encodings have encodings for null termination, and that stopping on null terminators was so pervasive and so terrible that it spawned an entire derivative-UTF-8 encoding so that normal C-style string operations worked on it (see Java Programming Language documentation, §4.4.7, Table 4.5 and other documentation concerning “Modified UTF-8”).

Assumed Valid Conversion API

Assumed valid conversion APIs are conversions that assume the input is already valid. This can drastically increased speed because checking for e.g. overlong sequences, illegal sequences, and other things can be entirely ignored. Note that it does not imply unbounded conversion, which is talked about just below. Assumed valid conversions are where the input is assumed valid; unbounded conversions are where the output is assumed to be appropriately sized/aligned/etc. Both are dangerous and unsafe and may lead to undefined behavior (unpredictable branching in algorithm, uncontrolled reads and stray writes, etc.) or buffer overruns. This does not mean it is always bad to have: Rust saw significant performance increases when they stopped verifying known-valid UTF-8 string data when constructing and moving around their strings, for both compile and run time workloads.

Lacking this API can result in speed drops, but not always.

Unbounded Conversion API

Unbounded conversions are effectively conversions with bounds checking on the output turned off. This is a frequent mainstay of not only old, crusty C functions but somehow managed to stay as a pillar of the C++ standard library. Unbounded conversions typically only take a single output iterator / output pointer, and generally have no built-in check to see if the output is exhausted for writing. This can lead to buffer overruns for folks who do not appropriately check or size their outputs. Occasionally, speed gains do come from unbounded writing but it is often more powerful and performance-impacting to have assumed valid conversion APIs instead. Combining both assumed valid and unbounded conversions tend to offer the highest performance of all APIs, pointing to a need for these APIs to exist even if they are not inherently safe.

Counting API

This is not too much of a big deal for APIs; nominally, it just allows someone to count how many bytes / code units / code points result from converting an input sequence from X to Y, without actually doing the conversion and/or without actually writing to an output buffer. There are ways to repurpose normal single/bulk conversions to achieve this API without requiring a library author to write it, but for this feature we will consider the explicit existence of such counting APIs directly because they can be optimized on their own with better performance characteristics if they are not simply wrappers around bulk/single conversion APIs.

Validation API

This is identical to counting APIs but for checking validity. Just like counting APIs, significant speed gains can be achieved by taking advantage of the lack of the need to count, write, or report/handle errors in any tangible or detailed fashion. This is mostly for the purposes of optimization, but may come in handy for speeding up general conversions where checking validity before doing an assumed-valid conversion may be faster, especially for larger blocks of data.

Extensible to (Runtime) User Encodings

This feature is for the ability to add encodings into the API. For example, if the API does not have functions for TSCII, or recognize TSCII, is it possible to slot that into an API without needing to abandon what principles or goals the library sets up for itself? There is also the question of whether or not the extensibility happens at the pre-build step (adding extra data files, adding new flags, and more before doing a rebuild) or if it is actually accommodated by the API of the library itself.

Bulk Conversions

Bulk conversions are a way of converting as much input as possible to fill up as much output as possible. The only stopping conditions for bulk conversions are exhausted input (success), not enough room in the output, an illegal input sequence, or an incomplete sequence (but only at the very end of the input when the input is exhausted). Bulk conversions open the door to using Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD) CPU instructions, GPU processing, parallel processing, and more to convert large regions of text at a time.

More notably, given a stable single conversion function, running that conversion in a loop would produce the same effect, but may be slower due to various reasons (less able to optimize the loop, cannot be easily restructured to use SIMD, and more). Bulk conversions get around that by stating up-front they will process as much data as possible.

Single Conversions

Single conversions are, effectively, doing “one unit of work” at a time. Whether converting Unicode one code point at a time or making iterators/views to go over a range of UTF-8 one bundle of non-error code units at a time, the implication here is that it uses minimal memory while guaranteeing that forward progress is made/work is done. It is absolutely not the most performant way of encoding, but it makes all other operations possible out of the composition of this single unit of work, so there’s that. If a single conversion is the only thing you have, you can typically build up the bulk conversion from it.

In the opposite case, where only a bulk conversion API is available, you can still implement a single conversion API. Just take a bulk API, break the input off into a subrange of size 1 from the beginning of the input. Then, call the bulk API. If it succeeds, that’s all you need to do. If not, you take the subrange and make it a subrange of size 2 from the start of the input. You keep looping up until the bulk API successfully converts that sub-chunk of input, or until input exhaustion. This method is, of course, horrifically inefficient. It is inadvisable to do this, unless correctness and feature set is literally your only goal with your library. Pressuring your user to provide a single conversion first, and then a bulk conversion, will provide far better performance metrics.

Custom Error Handling

This is just the ability for an user to change what happens on failure/error. Note that this is still possible if the algorithm just stops where the error is and hands you that information; you can decide to skip and/or insert your own kind of replacement characters. (Or panic/crash, write to log, trigger an event; whatever it is you like to do.) I did not think I needed this category, but after working with a bunch of different APIs it is surprising how many do not offer functions to handle this exact use case and instead force replacements or just throw this information into the sea of forgetfulness.

Updates Input Range / Updates Output Range

It’s split into two categories so that I can document which part of this that APIs handle appropriately. This is for when, on either success or error/failure, an API tells you where in the input it failed (the “input range” bit) if it did, and how much it wrote before it succeeded/failed (the “output range” bit). I was always annoyed by this part, and I only got increasingly annoyed that it seems most APIs just give you a big fat middle finger and tell you to go pound sand when it comes to figuring out what happened with the data. This also ties in with “custom error handling” quite a bit; not returning this information means that even if the user was prepared to do it on their own, it is fundamentally impossible to since they lose any possible information of where errors occurred or how much output was written out to not re-do work. Oftentimes, not getting this information results in you needing to effectively treat the entire buffer of input and the entire buffer of output as one big blob of No-Man’s-Land. You could have 4 GB of input data resulting in 8.6 GB of output data, and other APIs will literally successfully convert all but the very last byte and then simply report “we messed up, boss”.

Where did you mess up?

“🤷♂️”

Okay, but how far did you get before you messed up?

“🤷♂️🤷♂️”

Okay, okay, easy there, how much did you actually manage to get out before you think you messed up?

“🤷♂️¯\_(ツ)_/¯🤷♂️”

D… D-Do you remember ANYTHING about what we just spent several minutes of compute… doing…?

“Oh, hey boss! You ready to get started on all this data? It’s gonna be great.”

…

If that conversation is concerning and/or frustrating to you, then welcome to the world of string and text APIs in C and C++. It’s having this conversation, every damn day, day in and day out, dusk to dawn. It’s pretty bad!

Nevertheless

Now that we have all of our feature sets and know what we are looking for in an API, we can start talking about all of these libraries. The core goal here will be in dealing with the issues of each API and trying to fill out as much of the functionality as required in the tables. The goal will be to fill it all with ✅ in each row, indicating full support. If there is only partial support, we will indicate that with 🤨 and add notes where necessary. If there is no support, we will use a ❌.

ICU

ICU has almost everything about their APIs correct, which is great because it means we can start with an almost-perfect example of how things work out. They have a number of APIs specialized for UTF-8 and UTF-16 conversions (and we do benchmark those), but what we will evaluate here is the ucnv_convertEx API that serves at their basic and fundamental conversion primitive. Here’s what it looks like:

U_CAPI void ucnv_convertEx(

UConverter *targetCnv, UConverter *sourceCnv, // converters describing the encodings

char **target, const char *targetLimit, // destination

const char **source, const char *sourceLimit, // source data

UChar *pivotStart, UChar **pivotSource, UChar **pivotTarget, const UChar *pivotLimit, // pivot

UBool reset, UBool flush, UErrorCode *pErrorCode); // error code out-parameter

Some things done really well are the pErrorCode value and the pointer-based source/limit arguments. The error code pointer means that an user cannot ever forget to pass in an error code object. And, what’s more, is that if the value going into the function isn’t set to the proper 0-value (U_SUCCESS), the function will return a “warning” error code that the value going in was an unexpected value. This forces you to initialize the error code with UErrorCode error = U_SUCCESS;, then pass it in properly to be changed to something. You can still ignore what it sets the value to and pretend nothing ever happened, but you have, at least, forced the user to reckon with its existence. If someone is a Space CadetⓇ like me and still forgets to check it, well. That is on them.

Furthermore, the pointer arguments are also extraordinarily helpful. Taking a pointer-to-pointer of the first argument means that the algorithm can increment the pointer past what it has read, to successfully indicate how much data was read that produced an output. For example, UTF-8 may have anywhere from 1 to 4 code units of data (1 to 4 unsigned chars of data) in it. It is impossible to know how much data was read from a “successful” decoding operation, because it is a variable amount. Due to this, you cannot know how much was read/written without the function telling you, or you going backwards to re-do the work the function already did.

Updating the pointer value makes sure you know how much input was successfully read. An even better version of this updates the pointer only if the operation was successful, rather than just doing it willy-nilly. This is the way ICU works, and it is incredibly helpful when *pErrorCode is not set to U_SUCCESS. It allows you to insert replacement characters and/or skip over the problematic input if needed, allowing for greater control over how errors are handled.

Of course, there’s some things the ICU function is not perfectly good at, and that is having potentially unchecked functions for increased speed. One of the things I attempted to do while using ucnv_convertEx was pass in a nullptr for the targetLimit argument. The thinking was that, even if that was not a valid ending pointer, the nullptr would never compare equal to any valid pointer passed through the *target argument. Therefore, it could be used as a pseudo-cheap way to have an “unbounded” write, and perhaps the optimizer could take advantage of this information for statically-built versions of ICU. Unfortunately, if you pass in nullptr, ICU will immediately reject the function call with U_ILLEGAL_ARGUMENT as the error code. You also cannot do “counting” in a straightforward manner, since nullptr is not allowed as an argument to the target-parameters.

There are other dedicated functions you can use to do counting (“pre-flighting”, as the ICU documentation calls it since it also performs other functions), and there are also other conversion functions you can do to instrument the “in-between” part of the conversion too (that is serviced by the pivotStart, pivotSource, pivotTarget, and pivotLimit parameters). But, all in all it still contains much of the right desired shape of an API that is useful for text encoding, and does provide a way to do conversions between arbitrary encodings.

Single conversion or one-by-one conversions are supported by using the CharacterIterator abstraction, but it has very strange usability semantics because it iterators over UChars of 16 bits for UTF-16. Stitching together surrogate characters takes work and, in most cases, is almost certainly not worth it given the API and its design for this portion.

For going to UTF-8 or UTF-16 — which should cover the majority of modern conversions — there are also dedicated APIs for it, such as ucnv_fromUChars/ucnv_toUChars and u_strFromUTF8 and u_strToUTF8. These APIs take different parameters but share much of the same philosophies as the ucnv_convertEx described above, generally lacking a pivot buffer set of arguments since direct Unicode conversions need no in-between pivot. Unlike many of the other libraries compared / tested in this API and benchmark comparison we are doing, they do support quite an array of legacy encodings. The only problem is that adding new encoding conversions takes rebuilding the library and/or modifying data files to change what is available.

Despite being an early contender and having to base their API model around Unicode 1.0 and a 16-bit UChar (and thus settling on UTF-16 as the typical go-between), ICU’s interface has at least made amends for this by providing a rich set of functionality. It can be difficult to figure it all out and how to use it appropriately, but once you do it works well. It may fail in some regards due to not embracing different kinds of performant API surfaces but by-and-large it provides everything someone could need (and more, but we are only concerned with encoding conversions at this point).

simdutf

As its name states, simdutf wants to be a Single Instruction Multiple Data implementation (SIMD) for all of the Unicode Transformation Formats (UTFs). And it does achieve that; with speeds that tear apart tons of data and rebuild it in the appropriate UTF encoding, Professor Lemire earned himself a sweet spot in the SPIRE 2021: String Processing and Information Retrieval Journal/Symposium thingy for his paper, “Unicode at Gigabytes per Second”. The interface is markedly simpler than ICU’s; with no generic conversions to worry about and no special conversion features, simdutf takes the much simpler route of doing the following:

simdutf_warn_unused size_t convert_utf8_to_utf16le(

const char * input,

size_t length,

char16_t* utf16_output) noexcept;

simdutf_warn_unused result convert_utf8_to_utf16le_with_errors(

const char * input,

size_t length,

char16_t* utf16_output) noexcept;

simdutf_warn_unused size_t utf8_length_from_utf16le(

const char16_t* input,

size_t length) noexcept;

simdutf_warn_unused bool validate_utf8(

const char *buf,

size_t len) noexcept;

simdutf_warn_unused result validate_utf8_with_errors(

const char *buf,

size_t len) noexcept;

simdutf_warn_unused is a macro expanding to [[nodiscard]] or similar shenanigans like __attribute__((warn_unused)) on the appropriate compiler(s). The result type is:

struct result {

error_code error;

size_t position;

};

It rinses and repeats the above for UTF-8 (using (const )char*), UTF-16 (using (const )char16_t*), and UTF-32 (using (const )char32_t*).You will notice a couple of things lacking from this interface, before we get into the “SIMD” part of simdutf:

- How much input have I read, if something goes wrong?

- How much output have you written, if something goes wrong?

- How do I know if the buffer

utf8/16/32_outputis full?

For the version that is not suffixed with _with_errors, the first two cases are assumed not to happen: there are no output errors because it assumes the input data is well-formed UTF-N (for N in {8, 16, 32}). This only returns a size_t, telling you how much data was written into the *_output pointer. The assumption is that the entire input buffer was well-formed, after all, and that means the entire input buffer was consumed, assuming no problems. The *_with_errors functions have just one problem, however…

One, The Other, But Definitely Not Both

You are a smart, intelligent programmer. You know data coming in can have the wrong values frequently, due to either user error, corruption, or just straight up maliciousness. Out of an abundance of caution, you allocate a buffer that is big enough. You run the convert_utf8_to_utf16le_with_errors function on the input data, not one to let others get illegal data past you! And you were right to: some bad data came in, and the result structure’s error field has an enum error_code of OVERLONG: hah! Someone tried to sneak an overlong-UTF-8-encoded character into your data, to trap you! You pat yourself on the back, having caught the problem. But, now…. hm! Well, this is interesting. You have both an input pointer, and an utf16_output pointer, but there’s only one size_t position; field! Reading the documentation, that applies to the input, so… okay! You know where the badly-encoded overlong UTF-8 sequence is! But… uhm. Er.

How much output did you write again…?

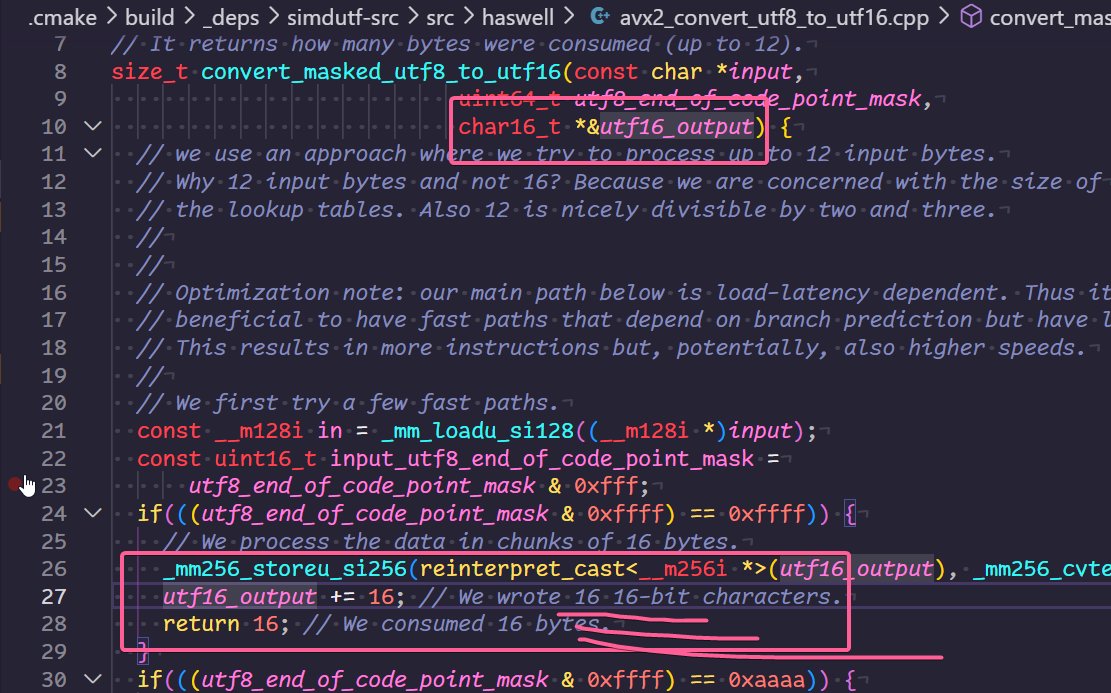

This is simdutf’s problem. If you do a successful read of all the input, and output all the appropriate data, the position field on the result structure tells you how many characters were written to the output. You know it was successful, so you know you’ve consumed all the input; that’s fine! But when an errors occurs? You only know how much input was processed before the error. Did you write 8.6 GB of data and only failed on the very last byte? Did you want to not start from the beginning of that 8.6 GB buffer and page in a shitload of memory? Eat dirt, loser; we’re not going to tell you squat. Normally, I’d be a-okay with that order of business. But there’s just one teensy, tiny problem with simdutf here! If you go into the implementations (the VARIOUS implementations, using everything from SSE2 to AVX2), you’ll notice a particular… pattern:

It. Knows.

It knows how much it’s been writing, and it just deigns not to tell you when its done. And I can see why it doesn’t pass that information back. After all, we all know how expensive it is to have an extra output_position field. That’s a WHOLE wasted size_t in the case where we read the input successfully and output everything nicely; it would be silly to include it! If we did not successfully read everything, what good can the input be anyhow?

Sarcasm aside, simdutf gets so many points for having routines that assume validity and do not, as well as length counting functions for input sequences and more, but just drops the ball on this last crucial bit of information! You either get to know the input is fully consumed and the output you wrote, or where you messed up in the input sequence, but you can’t get both.

Of course, it also doesn’t take buffer safety seriously either. Not that I blame simdutf for this: this has been an ongoing problem that C and C++ continue to not take seriously in all of its APIs, new and old. Nothing exemplifies this more than the standard C and C++ ways of “handling” this problem.

A Brief & Ranting Segue: Output Ranges and “Modern” C++

(Skip this rant by clicking here!)

Since the dawn of time, C and C++ have been on team “output limits are for losers”. I wrote an extensive blogpost about Output Ranges and their benefits after doing some benchmarks and citing Victor Zverovich’s work on fmtlib. At the time, that blogpost was fueled by rumblings of the idea that we do not need output ranges, or even a single output iterator (which is like an output pointer char16_t* utf16_output that Lemire’s functions take). Instead, we should take sink functions, and those sink functions can just be optimized into the speedy direct writes we need. The blog post showed that you can not only have the “sink” based API thanks to Stepanov’s iterator categorizations (an output iterator does exactly what a “sink” function is meant to do), but you can also get the performance upgrades to a direct write by having an output range composed of contiguous iterators of [T*, T*)/[T*, size_t]. This makes output ranges both better performing and, in many cases safer than both single-iterator and sink functions. So, when we standardized ranges, what did we do with old C++ functions that had signatures like

namespace std {

template <typename InputIt, typename OutputIt>

constexpr OutputIt copy(

InputIt first,

InputIt last,

OutputIt d_first);

}

the above? Well, we did a little outfitting and made the ones in std::ranges look like…

namespace std {

namespace ranges {

template <std::input_iterator I, std::sentinel_for<I> S, std::weakly_incrementable O>

requires std::indirectly_copyable<I, O>

constexpr copy_result<I, O> copy(

I first,

S last,

O result); // ... well, shit.

}

}

… Oh. We… we still only take an output iterator. There’s no range here. Well, hold on, there’s a version that takes a range! Surely, in the version that takes an input range, O will be a range too–

namespace std {

namespace ranges {

template <ranges::input_range R, std::weakly_incrementable O>

requires std::indirectly_copyable<ranges::iterator_t<R>, O>

constexpr copy_result<ranges::borrowed_iterator_t<R>, O> copy(

R&& r, // yay, a range!

O result); // ... lmao

}

}

Ah.

… Nice. Nice. Nice nice nice cool cool. Good. Great, even.

Fantastic.

One of the hilarious bits about this is that one of the penalties of doing SIMD-style writes and reads outside the bounds of a proper data pointer can be corruption and/or bricking of your device. If you have a pointer type for O result, and you start trying to do SIMD or other nonsense without knowing the size (or having an end pointer which can be converted into a size) with the single output pointer, on some hardware going past the ending boundary of the data and working on it means that you can, effectively, brick the device you’re running code on.

Now, this might not mean anything for std::(ranges::)copy, which might not rely on SIMD at all to get its work done. But, this does affect all the implementations that do want to use SIMD under the hood and may need to port to more exotic architectures; not having the size means you can’t be sure if/when you might do an “over-read” or “over-write” of a section of data, and therefore you must be extra pessimistic when optimizing on those devices. To be clear: a lot of computing does not run on such devices (e.g., all the devices Windows runs on and cares about do not have this problem). But, if you’re going to be writing a standard it might behoove us to actually give people the tools they need to not accidentally destroy their own esoteric devices when they use their SIMD instructions. When you have a range (in particular, a contiguous range with a size), you can safely work within the boundaries of both the input and output data and not trigger spurious failures/device bricking from being too “optimistic” with reads and writes outside of boundaries.

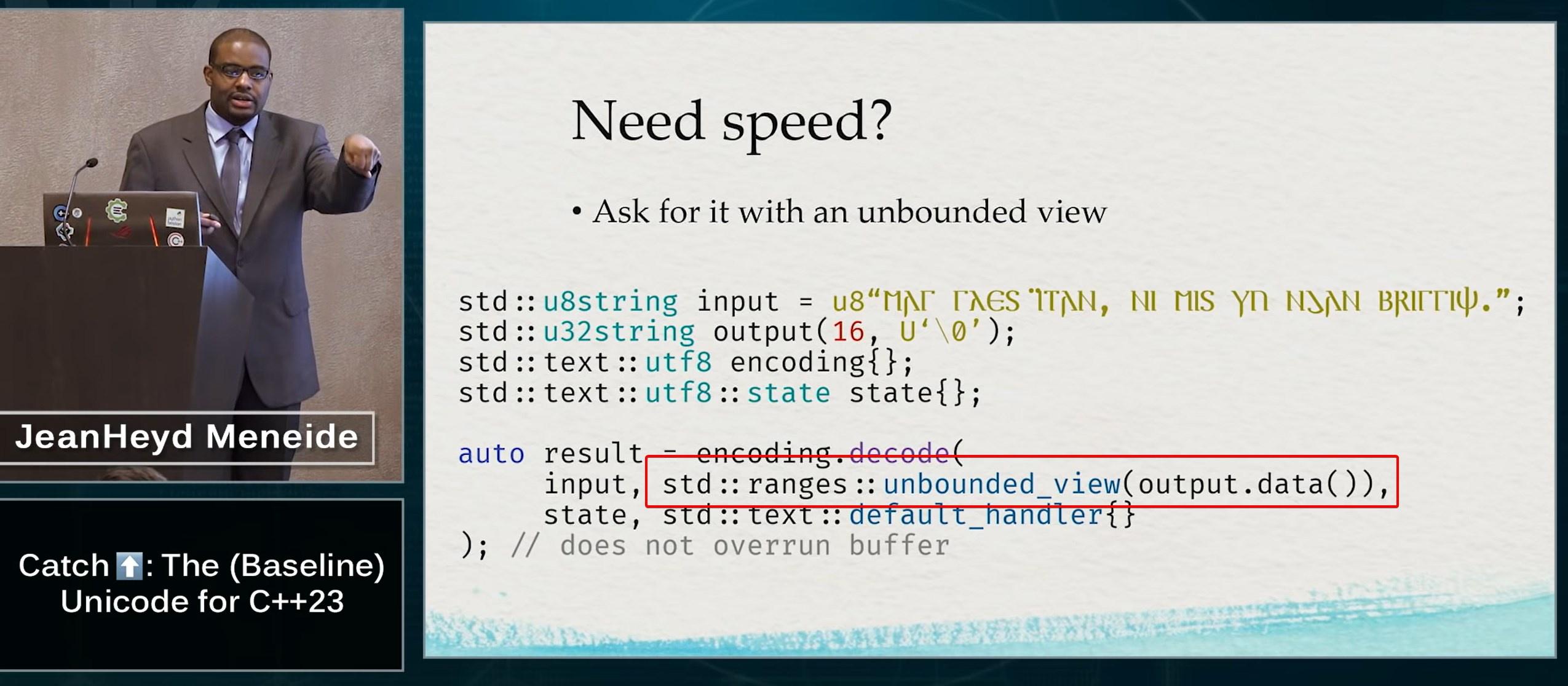

The weird part is that we also already have a range-based solution to “if I have to take a range, then I’m forced to bounds check against that range”. If you take an output range, you can also take an infinity range that simply does unbounded writes. This is something I’ve been using extensively since the earliest range-v3 days: unbounded_view. In fact, I gave a whole talk about how by using output ranges you can get safety by-default (the right default) and then get speed when you want it in an easily-searchable, greppable manner (timed video link):

It still baffles me that we can’t push people with our standard APIs to have decent performance metrics with safety first, and then ask people to deliberately pull the jar lid off to get to the dangerous and terrifying C++ mojo later. But, we continue to do this for C, C++, and similar code without taking a whole-library or whole-standard approach to being conscientious of the security vulnerability-rich environments we like to saddle developers with. These sorts of decisions are infectious because they are effectively the standards-endorsed interfaces, and routinely we suffer from logic errors which leak into unchecked buffer overruns and worse because the every-day tools employed in C and C++ codebases next to the usual logic we do are often the most unsafe possible tools we have. You cannot debug build or iterator-checking your way out of fundamentally poor design decisions. No matter how hard Stephan T. Lavavej or Louis Dionne or Jonathan Wakely iterator-safety the standard libraries in debug mode, leaving open the potential for gaping issues in our release builds is not helpful for the forward progress of C and C++ to be considered effective languages for an industry suffering from a wide variety of increasingly sophisticated security attacks.

But I digress.

The real problem here is that, in simdutf, if your data is not perfectly valid you are liable to waste work done in the face of a failed conversion. Kiss that 8.5999 GB goodbye and prepare to start from the beginning of that buffer all over again, because the interface still does not return how much output was written! In at least one win for Modern C++ interfaces, the new std::ranges algorithms in C++ did learn from the past at least a little bit. They return both the input iterator and the output iterator (std::ranges::copy_result<I, O>) passed into the function. simdutf has, unfortunately, been learning from the old C++ and C school of functions rather than the latest C++ school of functions! So, even if they both make the same unbounded-output mistake, simdutf doesn’t get the updated input/output perspective correct. And I really do mean the C school of function calls: the Linux Kernel has gotten into this same situation with trying to make a string copy function!

The Kernel folks are now deprecating strlcpy. They have begun the (long, painful?) maybe-migration to the newly decided-on strscpy. They are, once again, trying to convince everyone that the new strscpy is better than strlcpy, the same way the people who wrote strlcpy convinced everyone that it was better than strncpy. This time, they declare, they have really cracked the string copy functionality and came up with the optimal return values and output processing. And you know what, maybe for a bulk of the situations they care about, the people who designed strscpy are right! Unfortunately, you get tired of reading about the same return-value-but-changed-slightly or null-termination-but-we-handled-it-better-this-time-I-swear mistakes over and over again, you know? Even the article writer is resigned to this apparent infinity-cycle of “let’s write a new copy function” every decade or two (emphasis mine):

… That would end a 20-year sporadic discussion on the best way to do bounded string copies in the kernel — all of those remaining

strncpy()calls notwithstanding — at least until some clever developer comes up an even better function and starts the whole process anew.Jonathan Corbet, August 25th, 2022

I wish we would give everyone the input-and-output bounded copies with a full set of error codes so they could capture all the situations that matter, and then introduce strlcpy/strncpy/strscpy as optimizations where they are confident they can introduce it as such. But, instead, we’re just going to keep subtly tweaking/modifying/poking at the same damn function every 20 years. And keep introducing weird, messed up behavioral intrigues that drive people up the wall. It does give us all something to do, I guess! Clearly, we do not have enough things to be working on at the lowest levels of computing, beneath all else, except whether or not we’ve got our string copy functions correct. That’s the kind of stuff we need to be spending the time of the literal smartest people on the earth figuring out. Again. And get it right this time! For real. We promise. Double heart-cross and mega hope-to-die promise. Like SUPER-UBER pinky promise, it’s perfect this time, ultra swearsies!!

Ultra swearsies…

Rant Over

Regardless of how poorly output pointers are handled in the majority of C and C++ APIs, and ignoring the vast track record of people messing up null termination, sizes, and other such things, simdutf has more or less a standard interface offering most of the functionality you could want for Unicode conversions. Its combination of functions that do not check for valid input and ones that do (which are suffixed with _with_errors) allows for getting all of the information you need, albeit sometimes you need to make multiple function calls and walk over the data multiple times (e.g., call validate_utf8 before calling utf8_length_from_utf16le since the length function does not bother doing validation).

simdutf also does not bother itself with genericity or pivots or anything, because it solely works for a fixed set of encodings. This makes it interesting for Unicode cases (which is hopefully the vast majority of encoding conversions performed), but utterly useless when someone has to go battle the legacy dragons that lurk in the older codebases.

utf8cpp

utf8cpp is what it says on the tin: UTF-8 conversions. It also includes some UTF-16 and UTF-32 conversion routines and, as normal for most newer APIs, does not bother with anything else. It has both checked and unchecked conversions, and the APIs all follow an STL-like approach to storing information.

template <typename u16bit_iterator, typename octet_iterator>

u16bit_iterator utf8to16 (

octet_iterator start,

octet_iterator end,

u16bit_iterator result);

namespace unchecked {

template <typename u16bit_iterator, typename octet_iterator>

u16bit_iterator utf8to16 (

octet_iterator start,

octet_iterator end,

u16bit_iterator result);

}

You can copy-and-paste all of my criticisms for simdutf onto this one, as well as all my praises. Short, simple, sweet API, has an explicit opt-in for unchecked behavior (using a namespace to do this is a nice flex), and makes it clear what is on offer. As a side benefit, it also includes an utf8::iterator and an utf16::iterator classes to do iterator and view-like stuff with, which can help cover a pretty vast set of functionality that the basic functions cannot provide.

It goes without saying that extensibility is not built into this package, but it will be fun to test its speed. The way errors are handled are done by the user, which means that custom error handling / replacement / etc. can be done. Of course, just like simdutf, it thinks input iterator returns are for losers, so there’s no telling where exactly the error might be in e.g. an UTF-16 sequence or something to that effect. However, for ease-of-use, utf8cpp also includes a utf8::replace_invalid function to replace bad UTF-8 sequences with a replacement character sequence. It also has utf8::find_valid, so you can scan for bad things in-advance and either remove/replace/eliminate them in a given object yourself. (UTF-8 only, of course!)

encoding_rs/encoding_c

encoding_rs is, perhaps surprisingly, THE Rust entry point into this discussion. This will make it interesting from a performance perspective and an API perspective, since it has a C version — encoding_c — that provides a C-like API with a C++ wrapper around it where possible. It’s got a much weirder design philosophy than freely-creatable conversion objects; it uses static const objects of specific types to signal which encoding is which:

// …

/// The UTF-8 encoding.

extern ENCODING_RS_NOT_NULL_CONST_ENCODING_PTR const UTF_8_ENCODING;

/// The gb18030 encoding.

extern ENCODING_RS_NOT_NULL_CONST_ENCODING_PTR const GB18030_ENCODING;

/// The macintosh encoding.

extern ENCODING_RS_NOT_NULL_CONST_ENCODING_PTR const MACINTOSH_ENCODING;

// …

The types underlying them are all the same, so you select whichever encoding you need either by referencing the static const object in code or by using the encoding_for_label(uint8_t const* label, size_t label_len) function. You then start calling the (decoder|encoder)_(decode|encode)_(to|from)_utf16 functions (or using the object-oriented function calls that do exactly the same thing but by calling (decoder|encoder)->(decode|encode)_(to|from)_utf16 on a decoder/encoder pointer):

uint32_t encoder_encode_from_utf16(

ENCODING_RS_ENCODER* encoder,

char16_t const* src,

size_t* src_len,

uint8_t* dst,

size_t* dst_len,

bool last,

bool* had_replacements);

uint32_t encoder_encode_from_utf16_without_replacement(

ENCODING_RS_ENCODER* encoder,

char16_t const* src,

size_t* src_len,

uint8_t* dst,

size_t* dst_len,

bool last);

uint32_t decoder_decode_to_utf16(

ENCODING_RS_DECODER* decoder,

uint8_t const* src,

size_t* src_len,

char16_t* dst,

size_t* dst_len,

bool last,

bool* had_replacements);

uint32_t decoder_decode_to_utf16_without_replacement(

ENCODING_RS_DECODER* decoder,

uint8_t const* src,

size_t* src_len,

char16_t* dst,

size_t* dst_len,

bool last);

First off, I would just like to state, for the record:

FINALLY. Someone finally included some damn sizes to go with both pointers. This is the first API since ICU not to just blindly follow in the footsteps of either the standard library, C string functions, or whatever other nonsense keeps people from writing properly checked functions (with optional opt-outs for speed purposes). This is most likely due to the fact that this is a Rust library underneath, and the way data is handled is with built-in language slices (the equivalent of C++’s std::span, and the equivalent of C’s nothing because C still hates its users and wants them to make their own miserable structure type with horrible usability interfaces). encoding_rs unfortunately fails to provide functions that do no checking here. Weirdly enough, this functionality could be built in by allowing dst_len to be NULL, giving the “write indiscriminately into dst and I won’t care” functionality. But, encoding_rs just… does not, instead stating:

… UB ensues if any of the pointer arguments is

NULL,srcandsrc_lendon’t designate a valid block of memory ordstanddst_lendon’t designate a valid block of memory. …

So, that’s that. Remember that my qualm is not that there are unsafe versions of functions: it’s that there exist unsafe functions without well-designed, safe alternatives. encoding_rs swings all the way in the other direction, much like ICU, and says “unbounded writing is for losers”, leaving the use case out in the cold. The size_t pointer parameters still need to be as given, because the original Rust functions return sizes indicating how much was written. Rather than returning a structure (potentially painful to do in FFI contexts), these functions load up the new size values through the size_t* pointers, showing how much is left in the buffers.

Error handling can be done automatically for you by using the normal functions, with an indication that replacements occurred in the output bool* parameter has_replacements. Functions which want to apply some of their own handling and not just scrub directly over malformed sequences have to use the _without_replacement-suffixed functions.

Finally, the functions present here always go: to UTF-8 or UTF-16; or, from UTF-8 or UTF-16. It is your job to write a function that stiches 2 encodings together, if you need to go from one exotic/legacy encoding to another. This is provided in examples (here, and here), but not in the base package: transcoding between any 2 encodings is something you must specifically work out. The design is also explicitly not made to be extensible; what the author does is effectively his own package-specific hacks to pry the mechanisms and Traits open with his bare hands to get the additional functionality (such as in this crate).

This makes it a little painful to add one’s own encodings using the library, but it can technically be done. I will not vouch for such a path because when the author tells me “I explicitly made it as hard as possible to make it extensible”, I don’t take that as an invitation to go trying to force extensibility. Needless to say, the API was built for streaming and is notable because it is used in Mozilla Firefox and a handful of other places like Thunderbird. It is also frequently talked up as THE Rust Conversion API, but that wording has only come from, in my experience, Mozilla and Mozilla-adjacent folks who had to use the Gecko API (and thus influenced by them), so that might just be me getting the echo feedback from a specific silo of Rustaceans. But if it’s powering things like Thunderbird, it’s got to be good, especially on the performance front, right?

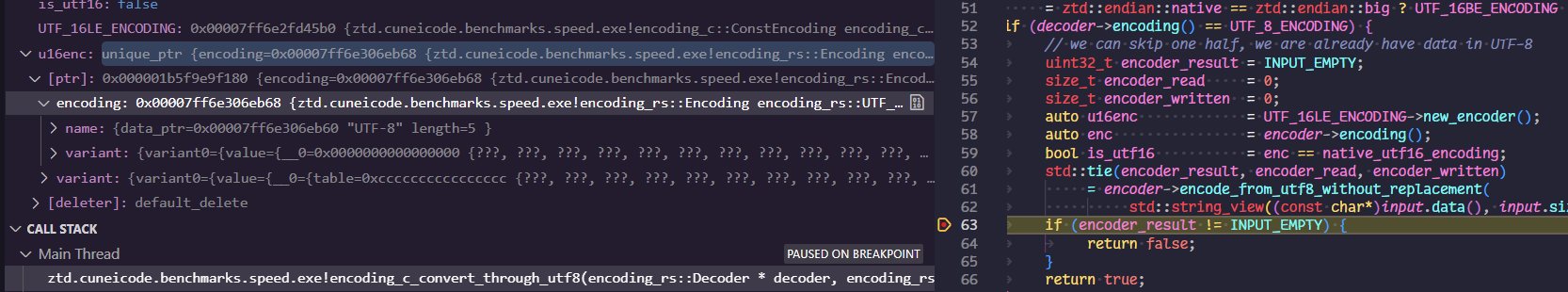

I did encounter a pretty annoying usability bug when trying to convert from UTF-8 to UTF-16 the “generic” way, and ended up with an unexplained spurious conversion failure that seemed to mangle the data. It was, apparently, derived from the fact that you cannot ask for an encoder (an “output encoding”) of an UTF-16 type, which is itself apparently a restriction derived from the WHATWG encoding specification:

4.3. Output encodings

To get an output encoding from an encoding encoding, run these steps:

- If encoding is replacement or UTF-16BE/LE, then return UTF-8.

- Return encoding

— §4.3 WHATWG Encoding Specification, June 20, 2022

Yes, you read that right. If the encoding is UTF-16, return the UTF-8 encoding instead. Don’t raise an error, don’t print that something’s off to console, just slam an UTF-8 in there. I spent a good moment doing all sorts of checks/tests, trying to figure out why the Rust code was apparently giving me an UTF-8 encoder when I asked for an UTF-16 encoder:

I’m certainly glad that encoding_rs cleaves that closely to the encoding specification, but you can backdoor this by simply generating a decoder for the encoding you are going from and directly calling decoder->decode_to_utf16_without_replacement(…). This, of course, begs the question of why we are following the specification this closely in the first place, if I can simply cheat my way out of the situation by shooting the encoder portion in the face and doing a direct conversion from the decoder half. It also begs the question of why the WHATWG specification willingly returns you a false encoding rather than raising an error. I’m sure there’s a good reason, but encoding_rs does not say it (other than stony-faced “it’s what the spec does”), and the WHATWG spec does not make it immediately obvious what the benefit of this is supposed to be. So I will simply regard it as the infinite wisdom of people 1,000 times my superior and scold myself for being too dumb to read the docs appropriately.

Topping off my Unicode Conversion troubles, encoding_rs (and it’s various derivatives like charset) don’t believe in UTF-32 as an encoding either. To be fair, neither does the WHATWG specification, but I’ve got applications trafficking in UTF-32 text (including e.g. the very popular Harfbuzz shaper and the Freetype API), so… I guess we’re just ignoring the hell out of those use cases and all of the wchar_t-based code out there in the world for *nix distributions.

Finally, there does not seem to be an “assume input is valid” conversion API either, despite the Rust ecosystem itself needing to have such functionality to drastically improve its own UTF-8 compile-time and run-time workloads for known-good strings. It’s not the end of the world to have neither unbounded nor assumed valid conversions, but it certainly means that there could be plenty of performance left out on the table from the API here. We also have to remember that encoding_rs’s job is strictly for web code, and maybe they just don’t trust anyone to do a conversion the unsafe way without endangering too-important data. Which is likely a fair call to make, but as somebody that’s trying to crush Execution and Wide Execution encodings from the C libraries like a watermelon between my thighs the library comes up disappointingly short on necessary functionality.

It has certainly colored my impression of Rust’s text encoding facilities if this is the end-all, be-all crate that was hyped up to me for handling things in Rust.

libiconv

libiconv has an interface similar to ICU, but entirely slimmed down. There is no pivot parameter, and instead of taking a pair of [T**, T*), it works on – perhaps strangely – [T**, size_t*):

size_t iconv(

iconv_t cd,

char ** inbuf,

size_t * inbytesleft,

char ** outbuf,

size_t * outbytesleft);

Initially, when I first encountered this, I thought libiconv was doing something special here. I thought they were going to use the nullptr argument for outbytesleft and outbuf to add additional modes to the functions, such as:

- input validation (

iconv(cd, inbuf, inbytesleft, nullptr, nullptr)), similar tovalidate_utf8from simdutf; - output size counting (

iconv(cd, inbuf, inbytesleft, nullptr, outbytesleft)), similar toutf16le_length_from_utf8from simdutf; and, - unbounded output writing (

iconv(cd, inbuf, inbytesleft, outbuf, nullptr)), similar to the lack of an “end” or “size” done by simdutf and utf8cpp and many other APIs.

libiconv was, of course, happy to NOT provide any of that functionality, nor give other functions capable of doing so either. This was uniquely frustrating to me, because the shape of the API was ripe and ready to provide all of these capabilities, and provide additional functions for those capabilities. Remember up above when, about how a bulk API can be repurposed for the goals of doing counting, unbounded output writing, and validation? This is exactly what was meant: using the provided API surface of libiconv could achieve all of these goals as a bulk encoding provider. You could even repurpose the iconv API to do one-by-one encoding (the sticking point being, of course, that performance would be crap).

The only thing going for libiconv, instead, is its wide variety of encodings it supports. Other than that, it’s a decent API surface whose potential is not at all taken advantage of, including the fact that despite having a type-erased encoding interface does not provide any way to add new encodings to its type-erased interface. (If you want to do that, you need to add it manually into the code and then recompile the entire library, giving no means of runtime addition that are not expressly added to it by some outside force.)

Additionally, the names given to “create iconv_t conversion descriptor objects” function is not stable. For example, asking for the “UTF-32” encoding does not necessarily mean you will be provided with the UTF-32 encoding that matches the endianness of the machine compiled for. (This actually became a problem for me because a DLL meant to be used for Postgres’s libiconv got picked up in my application once. Suffice to say, deep shenanigans ensued as my little endian machine suddenly started chugging down big-endian UTF-32 data.) In fact, asking for “UTF-32” does not guarantee there is any relationship between the encoding name you asked for and what is the actual byte representation; despite being a POSIX standard, there are no guarantees about the name <-> encoding mapping. There is also no way to control Byte Order Marks, which is hilarious when e.g. you are trying to compile the C Standard using LaTeX and a bad libiconv implementation (thanks Postgres) that inserts them poisons your system installation.

It is further infuriating that the error handling modes for POSIX can range from “stop doing things and return here to the user can take care of it”, “insert ASCII ? everywhere an error occurs” (glibc does this, and sometimes uses the Unicode Replacement Character when it likes), or even “insert ASCII * everywhere an error occurs” (musl-libc; do not ask me why they chose * instead of the nearly-universally-applied ?). How do you ask for a different behavior? Well, by building an entirely different libiconv module based on a completely different standard library and/or backing implementation of the functionality. Oh, the functionality comes from a library that is part of your core distribution? Well, just figure out the necessary linker and loader flags to get the right functions first. Duh!

Of course. How could I be such a bimbo! Just need to reach into my system and turn into a mad dog frothing at the mouth about encodings to get the behavior that works best for me. I just need to create patches and hold my distribution updates at gunpoint so I can inject the things I need! So simple. So easy!!

In short, libiconv is a great API tainted by a lot of exceedingly poor specification choices, implementation choices, and deep POSIX baggage. Its lack of imagination for a better world and contentment with a broken, lackluster specification is only rivaled by its flaccid, uninspired API usage and its crippling lack of behavioral guarantees. At the very least, GNU libiconv provides a large variety of encodings, but lacks extensibility or any meaningful way to override or control how specific encoding conversions behave, leaving you at the mercy of the system.

In other words, it behaves exactly like every other deeply necessary C API in the world, so no surprises there.

boost.text

This is perhaps the spiritually most progressive UTF encoding and decoding library that exists. But, while having the ability to perhaps add more encodings to its repertoire, it distinctly refuses to and instead consists only of UTF-based encodings. There is a larger, more rich offering of strictly Unicode functionality (normalization, bidirectional algorithms, word break algorithms, etc.) that the library provides, but we are — perhaps unfortunately — not dealing with APIs outside of conversions for now. Like utf8cpp and simdutf before it, it offers simple free functions for conversions:

template <std::input_iterator I, std::sentinel_for<I> S,

std::output_iterator<uint16_t> O>

transcode_result<I, O> transcode_to_utf16(

I first,

S last,

O out);

It also offers range-based solutions, more fleshed out that utf8cpp’s. These are created from a boost::text::as_utfN(...) function call, (where N is {8, 16, 32}) and produce iterator/range types for going from the input type (deduced from the pointer (treated as a null-terminated C-string) or from the range’s value type) to the N-deduced output type.

As usual, the criticism of “please do not assume unbounded writes are the only thing I am interested in or need” applies to boost.text’s API here. Thankfully, it does something better than simdutf or utf8cpp: it gives back both the incremented first and the incremented out iterators. Meaning that if I passed 3 pointers in, I will get 2 updated pointers back, allowing me to know how much was read and how much was written. There is an open question about whether or not one can safely subtract pointers that may have a difference larger than PTRDIFF_MAX without invoking undefined behavior, but I have resigned myself that it is more or less an impossible problem to solve in a C and C++ standards-compliant way for now (modulo relying on not-always-present uintptr_t).

boost.text’s unfortunate drawback is in its error handling scheme. You are only allowed to insert one (1) character — maybe — through its error handler abstraction, and only when using its iterator-based replacement facilities. During it’s transcode_to_utfN functions, it actively refuses to do anything other than insert the canonical Unicode replacement character, which means you cannot get the fast iteration functions to stop on bad data. It will just plow right on through, stick the replacement character, and then smile a big smile at you while pretending everything is okay. This can have some pretty gnarly performance implications for folks who want to do things like, say, stop on an error or perform some other kind of error handling, forcing you to use the (less well-performing) iterator APIs.

But this is par-for-the-course for boost.text; it was made to be an incredibly opinionated API. I personally think its opinionated approach to everything is not how you get work done when you want to pitch it to save C and C++ from its encoding troubles, and when I sent my mailing list review for it when I still actively participated in Boost I very vocally explained why I think it’s the wrong direction. It is, in fact, the one of the bigger reasons I got involved with the C++ Standards Committee SG16: someone was doing something wrong on the internet and I couldn’t let that pass:

It’s still not a bad library. It has less features and ergonomics versus simdutf, but the optimizations Zach Laine put into the encoding conversion layer are slick and at times compete with simdutf, when it’s working. (More on that later, when we get to the benchmarks.)

Standard C and C++

I am not even going to deign to consider C++ here. The APIs for doing conversions were so colossally terrible that they were not only deprecated in C++17 (NOTE: not yet removed, but certainly deeply discouraged by existing compiler flags). I myself have suffered an immensely horrible number of bugs trying to use the C++ version from the <codecvt>, and users of my sol2 library have also suffered from the exceedingly poor implementation quality derived from an even worse API that does not even deserve to be mentioned in the same breath as the rest of the APIs here. You can read some of the criticisms:

wstring_convertsuckswstring_convertconstructor repeat many times causes performance degradationstd::codecvt::outin LLVM libc++ does not advance in and out pointers

<codecvt> and std::wstring_convert are dead and I will never hide how glad I am we put that thing in the trash can.

I’m also less than thrilled about the C Standard API for conversions. There are a number of problems, but I won’t regale you all of the problems because I wrote a whole paper about it so I could fix it eventually in C. It did not make C23 because a last minute objection to the structure of the wording handling state ended up costing the paper it’s ability to make the deadline. Sorry; despite being the project editor I am (A) new to this, (B) extremely exhausted, and (C) not good at this at all, unfortunately!

Nevertheless, the C standard does not support UTF-16 as a wide encoding right now, which violates at least 6 different existing major C platforms today. Even if the wide (wchar_t) encoding is UTF-32, the C API is still fundamentally incapable of representing many of the legacy text encodings it is supposed to handle in the first place. This has made even steely open source contributors stared slack-jawed at embattled C libraries like glibc, which have no choice but to effectively jettison themselves into nonsense behavior because the C standard provides no proper handling of things. This case, in particular, arises when Big5-HKSCS needs to return two UTF-32 code points (e.g. U"\U00CA\U+0304") for certain input sequences (e.g. "Ê̄"):

oh wow, even better: glibc goes absolutely fucking apeshit (returns 0 for each

mbrtowc()after the initial one that eats 2 bytes; hereinwcmodified to write the resulting character)— наб, July 9, 2022

In fact, implementations can do whatever they want in the face of Big5-HKSCS, since it’s outside the Standard’s auspices:

…

Florian raised a similar issue in May of 2019 and the general feedback at that time was that BIG5-HKSCS is simply not supported by ISO C. I expect the same answer from POSIX which is harmonized with ISO C in this case.

If BIG5-HKSCS is not supported, then the standard will have nothing to say about which values can be returned after the first or second input bytes are read. …

— Carlos O’ Donnell, March 30, 2020

And indeed, the standard cannot handle it. Both because of the assumption that a single wchar_t (one UTF-32 code unit, a single char32_t) can represent all characters from any character set, and the horrible API design that went into the mbrtowc/wcrtomb/etc. function calls. My paper details much of the pitfalls and I won’t review them exhaustively here, but suffice to say everyone who has had their head in the trenches for a long time has conclusively reached the point where we know the original APIs are bunk garbage. I have no intention of rehashing why these utilities are garbage and do not work, and seek only to supplant them and then drive them back into the burning hell whence forth they deigned to sputter out of.

Also, fun fact: the <uchar.h> functions which do attempt to do Unicode conversions (but use the execution encoding as the “go between”, so if you do not have a UTF-8 multibyte encoding every encoding is lossy and worthless) are not present on Mac OS. Which is weird, because Mac OS went all-in on UTF-8 encoding conversions as its char* encoding in all of its languages, so it could just… make that assumption and ignore all the BSD-like files left lurking in the guts of the OS. But they don’t, so instead they just provide… nothing.

All in all, if the C standard was at least capable — or the C++ standard ever rolled its sleeves up and design something halfway good — we might not be in this mess. But we are, driving the reason for this whole article. Of course, some platforms realized that the C and C++ standards are trash, so they invented their own functions. Like, for example, the Win32 folks.

Windows API

The Windows API has 2 pretty famous functions for doing conversions: WideCharToMultiByte and MultiByteToWideChar. They convert from a given code page to UTF-16, and from UTF-16 to a given code page. The signatures from MSDN look as follows:

int WideCharToMultiByte(

UINT CodePage,

DWORD dwFlags,

_In_NLS_string_(cchWideChar)LPCWCH lpWideCharStr,

int cchWideChar,

LPSTR lpMultiByteStr,

int cbMultiByte,

LPCCH lpDefaultChar,

LPBOOL lpUsedDefaultChar

);

int MultiByteToWideChar(

UINT CodePage,

DWORD dwFlags,

_In_NLS_string_(cbMultiByte)LPCCH lpMultiByteStr,

int cbMultiByte,

LPWSTR lpWideCharStr,

int cchWideChar

);

There is no “one by one” API here; just bulk. And, similar to the criticisms levied at simdutf, the standard library, and so many other APIs, they only have a single return int that is used as both the error code channel and the return value for the text. (We will ignore that they are using int, which definitely means you cannot be using larger than 4 GB buffers, even on a 64-bit machine, without getting a loop prepped to do the function call multiple times.) I am willing to understand Windows’s poor design because this API is some literal early-2000s crap. I imagine with all the APIs Windows cranks out regularly, they might have an alternative to this one by now. But if they do, (A) I cannot find such an API, and (B) contacting people who literally work (and worked) on the VC++ runtime have started in no uncertain terms that the C and C++ code to use for these conversions is the WideCharToMultiByte/MultiByteToWideChar interfaces.

So, well, that’s what we’re using.

This API certainly suffers from its age as well. For example, it does things like assume you would only want to insert 1 replacement character (and that the replacement character can fit neatly in one UTF-16 code unit). This was fixed in more recent versions of windows with the introduction of the MB_ERR_INVALID_CHARS flag that can be passed to the dwFlags parameter, where the conversion simply fails if there are invalid characters. Of course, the same problem as simdutf manifests but in an even worse fashion. Because the error code channel is the same as the “# of written bytes” channel (the return value), returning an error code means you cannot even communicate to the user where you left off in the input, or how much output you have written. If the conversion fails and you want to, say, insert a replacement u'\xFFFD' or u'?' by yourself and skip over the single bit of problematic input, you simply cannot because you have no idea where in the output to put it. You also don’t know where the error has occurred in the input. It’s the old string conversion issue detailed at the start of this article, all over again, and it’s infuriating.

ztd.text

Turns out I have an entire slab of documentation you can read about the design, and an entire article explaining part of that design out, so I really won’t bother explaining ztd.text. It’s the API I developed, the API mentioned in the video linked above, and what I’ve poured way too much of my time into for the sole purpose of saving the C and C++ landscape from its terrible encoding woes. I have people reaching out from different companies already attempting re-implementations of the specification for their platforms, and progress continues to move forward.

It checks every single box in the table’s row for the desired feature sets, obviously. If it didn’t I would have went back and whipped my API into shape to make sure it did, but I didn’t have to because unlike just about every other API in this list it actually paid attention to everything that came before it and absorbed their lessons. I didn’t make obvious mistakes or skip over use cases because, as it turns out, listening and learning are really, really powerful tools to prevent rehashing 30 year old discussions.

Wild, isn’t it?

So… What Happens Now?

We listed a few criteria and talked about it, so let’s try to make a clear table of what we want out of an API and what each library gives us in terms of conversions. As a reminder, here’s the key:

- ✅ Meets all the necessary criteria of the feature.

- ❌ Does not meet all the necessary criteria of the feature.

- 🤨 Partially meets the necessary criteria with caveats or addendums.

And here’s how each of the libraries squares up.

| Feature Set 👇 vs. Library 👉 | ICU | libiconv | simdutf | encoding_rs/encoding_c | ztd.text |

| Handles Legacy Encodings | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Handles UTF Encodings | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | 🤨 | ✅ |

| Bounded and Safe Conversion API | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Assumed Valid Conversion API | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Unbounded Conversion API | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Counting API | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Validation API | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Extensible to (Runtime) User Encodings | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Bulk Conversions | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Single Conversions | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Custom Error Handling | ✅ | 🤨 | 🤨 | ✅ | ✅ |

| Updates Input Range (How Much Read™) | ✅ | ✅ | 🤨 | ✅ | ✅ |

| Updates Output Range (How Much Written™) | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Feature Set 👇 vs. Library 👉 | boost.text | utf8cpp | Standard C | Standard C++ | Windows API |

| Handles Legacy Encodings | ❌ | ❌ | 🤨 | 🤨 | ✅ |

| Handles UTF Encodings | ✅ | ✅ | 🤨 | 🤨 | ✅ |

| Bounded and Safe Conversion API | ❌ | ❌ | 🤨 | ✅ | ✅ |

| Assumed Valid Conversion API | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Unbounded Conversion API | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Counting API | ❌ | 🤨 | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Validation API | ❌ | 🤨 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Extensible to (Runtime) User Encodings | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Bulk Conversions | ✅ | ✅ | 🤨 | 🤨 | ✅ |

| Single Conversions | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Custom Error Handling | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Updates Input Range (How Much Read™) | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Updates Output Range (How Much Written™) | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

Briefly covering the “🤨” for each library/API:

- libiconv: error handling and insertion of replacements is implementation-defined, and the replacements are also implementation-defined, and whether or not it even does it is implementation-defined, and whether or not it’s any good is – you guessed it! — implementation-defined.

- simdutf: it only reports how much output was read one success, and only reports how much input was read if you’re careful, making inserting custom handling a lot harder than is necessary.

- encoding_rs: cannot handle UTF-32 from C or C++ (but gets it for free in Rust because you can convert to Rust

char, which is a Unicode Scalar Value). - boost.text: this one has an “❌” for custom error handling, despite enabling it for its ranges, because its bulk transcoding functions refuse you the opportunity or chance to do that and they do not provide functions to allow you to change it.

- utf8cpp: it does not provide counting and validation APIs for all UTF functions, so even if restricted to purely UTF functions validation and counting must be done by the end-user, or through using iterators with a slower API.

- Standard C: it’s trash.

- Standard C++: provides next-to-nothing of its own that is not sourced from C, and when it does it somehow makes it worse. Also trash.

-

Windows API: it does not handle UTF-32. From the documentation of its Code Page identifiers (emphasis mine):

12000 utf-32 Unicode UTF-32, little endian byte order; available only to managed applications 12001 utf-32BE Unicode UTF-32, big endian byte order; available only to managed applications UTF-32 continues to be for losers, apparently!

This is the full spread. Every marker should be explained above; if something is missing, do let me know, because I am going to routinely reference this table as the Definitive™ Feature List for all of these libraries from now until I die and also in important articles and journals. I spent way too much time investigating these APIs, suffering through their horrible builds, and knick-knack-patty-whacking these APIs and benchmarks and investigations together. I most certainly never want to touch libiconv again, and even though I’m tired as hell I’ve already put “remake ztd.text in Rust so I can have an UTF-32 conversion as part of a Rust text library, For God’s Sake” on my list of things to do. (Or someone else will get to do it before I do, which would be grrreeat.)

But… Where’s Your C API?

Right. I said I was going to use all of this to see if we can make an API in C that matches the power of my C++ one, and learns all the necessary lessons from all the C and C++ APIs that litter the text encoding battlefield. A C API for working with text that covers all of the use cases and basis that already exist in the industry. Which is exactly what I did when I created ztd.cuneicode, a powerful C library that allows runtime extension and uncompromised speed while absorbing the lessons of Stepanov’s STL, iconv’s interface, and libogonek/ztd.text’s state handling apparatus. The time has come to explain the ultimate C encoding API to you

… Part 2!

Sorry! It turns out this article has quite literally surpassed 10,000 words and quite frankly there’s still a LOT to talk about. The next one might another 10,000 word banger (and I sincerely do not want it to be because then that means I will be writing far past New Years and into 2023). So, the actual design of the C library, its benefits, and more, will all come later. But I won’t just leave you empty-handed! In fact, here’s a little teaser…

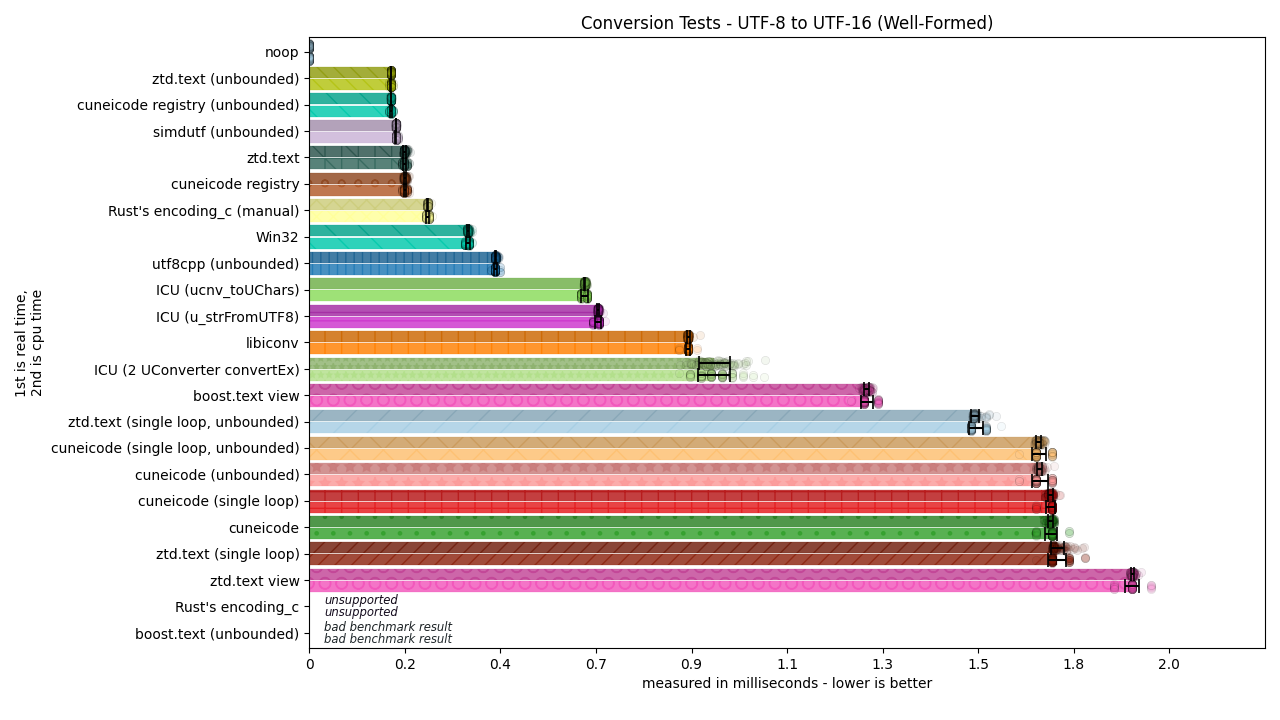

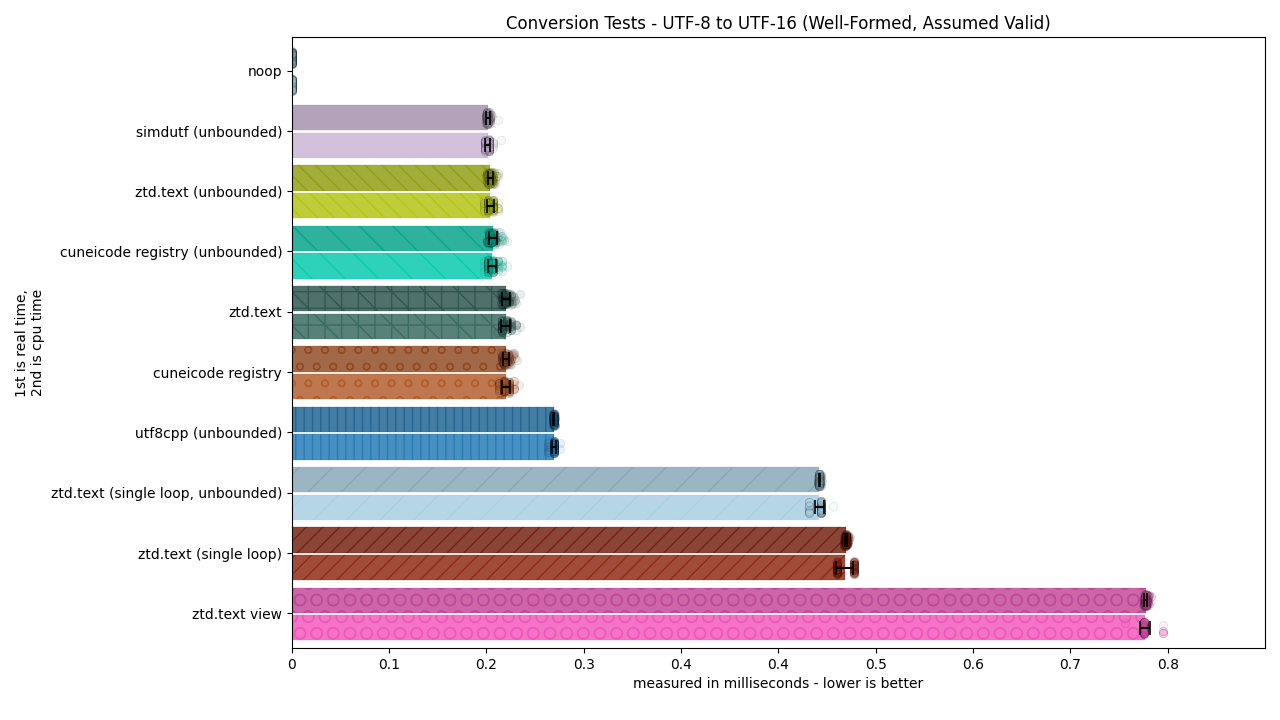

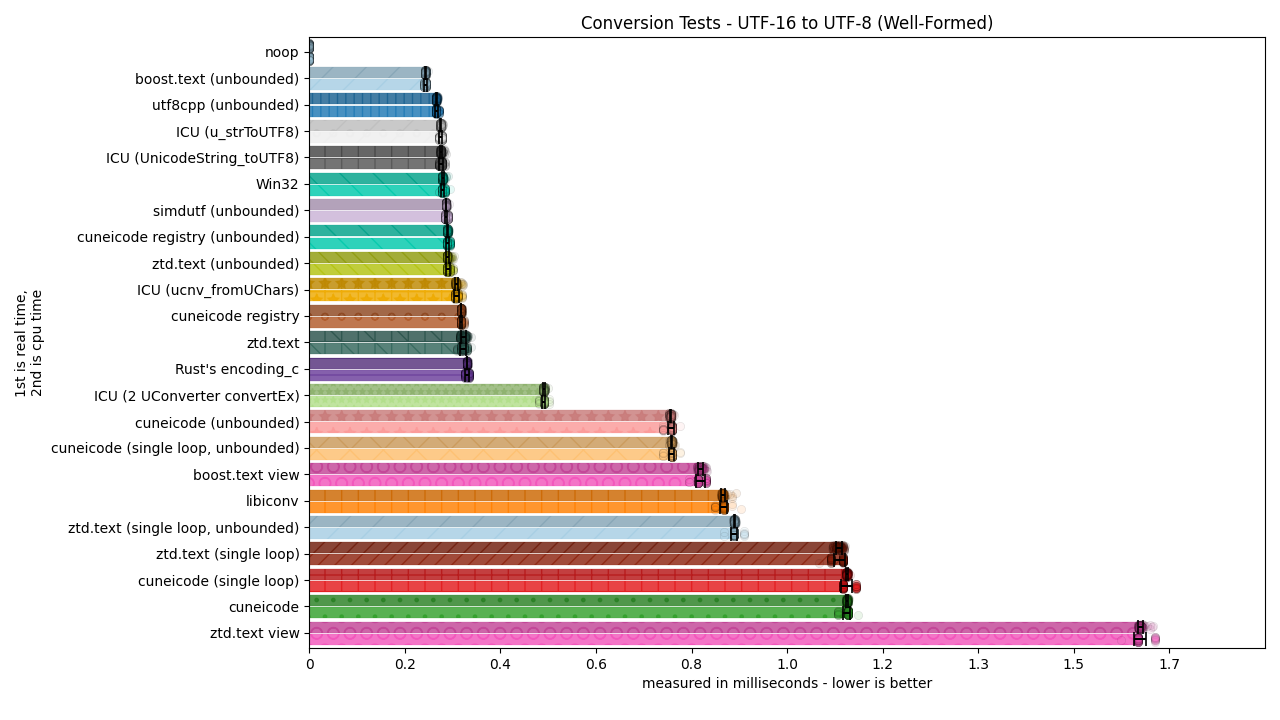

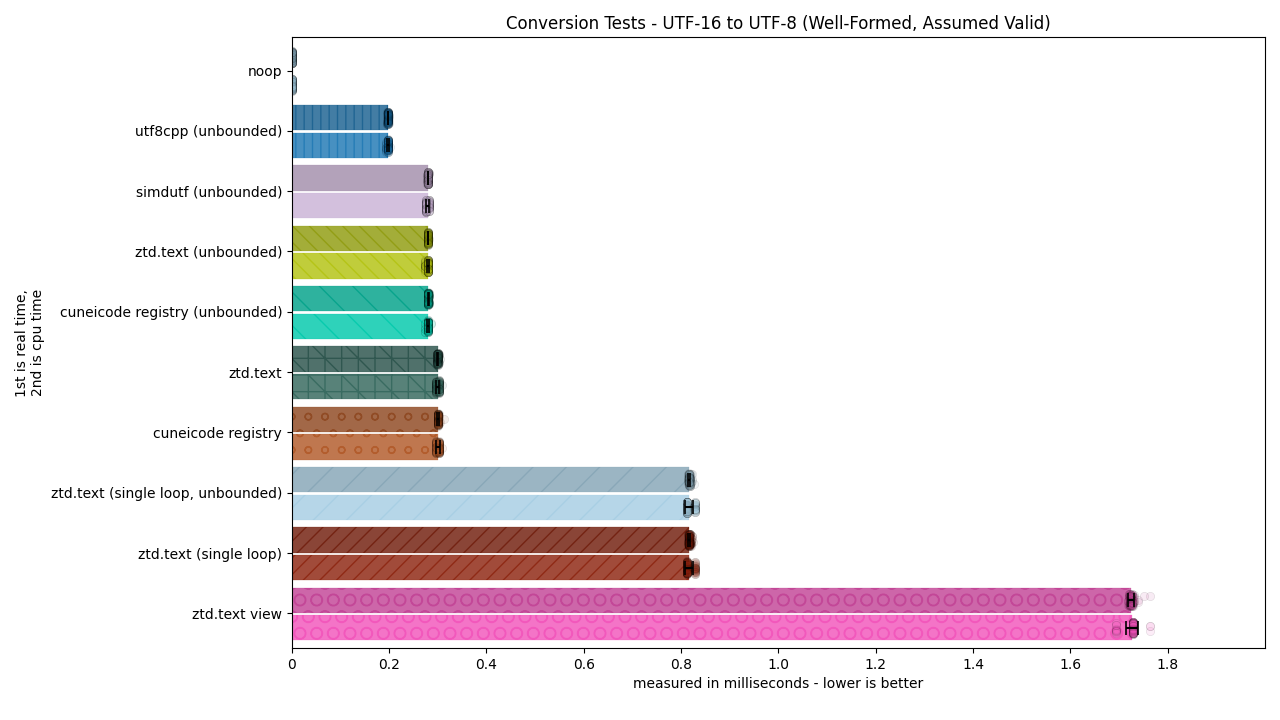

Nyeheheh, such beautiful graphs…!

See you soon 💚.

- Thumbnail / Title Feature art done by Nemo (@WusdisWusdat) (There’s a whole comic, but it’s being Saved™ for a whole new blog post!)

- “a” Emote art done by Framebuffer (@framebuffer)

- Exhausted Phone art done by Cynthia (@PixieCatSupreme)

- Concerned Emote art done by Queenie B