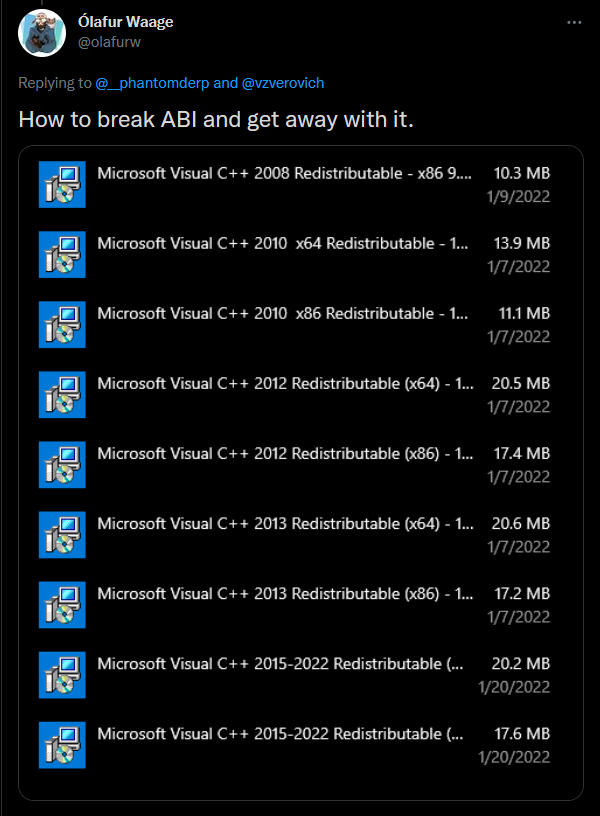

After that first Firebrand of an article on Application Binary Interface (ABI) Stability, I’m not sure anyone expected this to be the title of the next one, huh? It seems especially bad, given this title is in direct contradiction to a wildly popular C++ Weekly Jason Turner did on the exact same subject:

Not only is Jason 110% thoroughly correct in his take, I deeply and fervently agree with him. My last article on the subject of ABI - spookily titled “Binary Banshees and Digital Demons” - also displayed how implementers not only back-change the standard library to fit the standard (and not the other way around) when they can get away with it, but also that occasionally threaten the existence of newly introduced features using ABI as a cudgel. But, if I’ve got such a violent hatred for ABI Stability and all of its implications,

why would I claim we need to save it?

Should it not be utterly destroyed and routed from this earth? Is it not the anti-human entity that I claimed it was in my last article? Could it be that I was infected by Big Business™ and Big MoneyⓇ and now I’m here to shill out for ABI Stability? Perhaps I’ve on-the-low joined a standard library effort and I’m here as a psychological operation to condition everyone to believing that ABI is good. Or maybe I’ve just finally lost my marbles and we can all start ignoring everything I write!

(Un?)Fortunately, none of that has happened. My marbles are all still there, I haven’t been bought out, and the only standard library I’m working on is my own, locked away in a private repository on a git server in some RAID storage somewhere. But, what I have realized steadily is that no matter how much I agitate and evangelize and etc. etc. for a better standard library, and no matter how many bit containers I write that run circles around MSVC STL’s purely because I get to use 64-bit numbers for my bit operations while they’re stuck on 32-bit for Binary Compatibility reasons, these systems aren’t going to change their tune just for li’l old me. Or Jason Turner. Or anyone else, really, who’s fed up with losing performance and design space to legacy choices when we quite literally were just not smart enough to be making permanent decisions like this. This doesn’t mean we need to give up, however. After all, there’s more than one way to break an ABI:

Silliness aside, it is important to make sure everyone is up to speed on what an “ABI” really is. Let’s look at ABI - this time, from the C side - and what it prevents us from fixing.

The Monster - Application Binary Interface

Application Binary Interface, which we will be colloquially referring to as ABI because that’s a whole mouthful to say, is the invisible contract you sign every time you make a structure or write a function in C or C++ code and actually use it to do anything. In particular, it is the assumptions the compiler makes about how exactly the bit-for-bit representation and the usage of the computer’s actual hardware resources when it negotiate things that lie outside of a singular routine. This includes things like:

- the position, order, and layout of members in a

struct/class; - the argument types and return type of single function (C++-only: and any relevant overloaded functions);

- the “special members” on a given

class(C++-only); - the hierarchy and ordering of virtual functions (C++-only);

- and more.

Because this article focuses on C, we won’t be worrying too much about the C++ portions of ABI. C also has much simpler ways of doing things, so it effectively boils down to two things that matter the most:

- the position, order, and layout of members in a

struct; and, - the argument types and return type of a function.

Of course, because C++ consumes the entire C standard library into itself nearly wholesale with very little modifications, C’s ABI problems become C++’s ABI problems. In fact, because C undergirds way too much software, it is effectively everyone’s problem what C decides to do with itself. How exactly can ABI manifest in C? Well, let’s give a quick example:

The C ABI

C’s ABI is “simple”, in that there is effectively a one-to-one correspondence between a function you write, and the symbol that gets vomited out into your binary. As an example, if I were to declare a function do_stuff, that took a long long parameter and returned a long long value to use, the code might look like this:

#include <limits.h>

extern long long do_stuff(long long value);

int main () {

long long x = do_stuff(-LLONG_MAX);

/* wow cool stuff with x ! */

return 0;

}

and the resulting assembly for an x86_64 target would end up looking something like this:

main:

movabs rdi, -9223372036854775807

sub rsp, 8

call do_stuff

xor eax, eax

add rsp, 8

ret

This seems about right for a 64-bit number passed in a single register before a function call is made. Now, let’s see what happens if we change the argument from long long, which is a 64-bit number in this case, to something like __int128_t:

#include <limits.h>

extern __int128_t do_stuff(__int128_t value);

int main () {

__int128_t x = do_stuff(-LLONG_MAX);

return 0;

}

Just a type change! Shouldn’t change the assembly too much, right?

main:

sub rsp, 8

mov rsi, -1

movabs rdi, -9223372036854775807

call do_stuff

xor eax, eax

add rsp, 8

ret

… Ah, there were a few changes. Most notably, we’re not only touching the rdi register, we’re messing with rsi too. This shows us, already, that without even seeing the inside of the definition of do_stuff and how it works, the compiler has forged a contract between itself and the people who write the definition of do_stuff. For the long long version, they expect only 1 register to be used - and it HAS to be rdi - on x86_64 (64-bit) computers. For the __int128_t version, they expect 2 registers to be used - rsi AND rdi - to be used to contain all 128 bits. It sets this up knowing that whoever is providing the definition of do_stuff is going to use the exact same convention, down to the registers in your CPU. This is not a source code-level contract: it is one forged by the compiler, on your behalf, with other compilers and other machines.

This is the Application Binary Interface.

We note that the problem we highlight is very specific to C and most C-like ABIs. As an example, here is the same main with the __int128_t-based do_stuff’s assembly in C++:

main:

push rax

movabs rdi, -9223372036854775807

mov rsi, -1

call _Z8do_stuffn

xor eax, eax

pop rcx

ret

This _Z8do_stuffn is a way of describing that there’s a do_stuff function that takes an __int128_t argument. Because the argument type gets beaten up into some weird letters and injected into the final function name, the C++ linker can’t be confused about which symbol it likes, compared to the C one. This is called name mangling. This post won’t be calling for C to embrace name mangling - no implementation will do that (except for Clang and its [[overloadable]] attribute) - which does make what we’re describing substantially easier to go over.

Still, how precarious can C’s direct/non-mangled symbols be, really? Right now, we see that the call in the assembly for the C-compiled code only has one piece of information: the name of the function. It just calls do_stuff. As long as it can find a symbol in the code named do_stuff, it’s gonna call do_stuff. So, well, let’s implement do_stuff!

ABI from the Other Side

The first version is the long long one, right? We’ll make it a simple function: checks if it’s negative and returns a specific number (0), otherwise it doesn’t do anything. Here’s our .c file containing the definition of do_stuff:

long long do_stuff (long long value) {

if (value < 0) {

return 0;

}

return value;

}

It’s kind of like a clamp, but only for negative numbers. Either way, let’s check what this bad boy puts out:

do_stuff:

xor eax, eax

test rdi, rdi

cmovns rax, rdi

ret

Ooh la la, fancy! We even get to see a cmovns! But, all in all, this assembly is just testing the value of rdi, which is good! It’s then handing it back to the other side in rax. We don’t see rax in the code with main because the compiler optimized away our store to x. Still, the fact that we’re using rax for the return is also part of the Application Binary Interface (e.g., not just the parameters, but the return type matters). The compilers chose the same interpretation on both the inside of the do_stuff function and the outside of the do_stuff function. What does it look like for an __int128_t? Here’s our updated .c file:

__int128_t do_stuff (__int128_t value) {

if (value < 0) {

return 0;

}

return value;

}

And the assembly:

do_stuff:

mov rdx, rsi

xor esi, esi

xor ecx, ecx

mov rax, rdi

cmp rdi, rsi

mov rdi, rdx

sbb rdi, rcx

cmovl rax, rsi

cmovl rdx, rcx

ret

… Oof. That’s a LOT of changes. We see both rsi and rdi being used, we’re using a cmp (compare) on rsi and rdi, and we’re using a Subtract with Borrow (sbb) to get the right computation into the rcx register. Not only that, but instead of just using the rax register for the return (from cmovl), we’re also applying that to the rdx register too (with a similar cmovl). So there’s an expectation of 2 registers containing the return value, not just one! So we’ve clearly got two different expectations for each set of functions. But… well, I mean, come on.

Can it really break?

How bad would it be if I created an application that compiled with the 64-bit version initially, but was somehow mistakenly linked with the 128-bit version through bad linker shenanigans or other trickery?

Causing Problems (On Purpose)

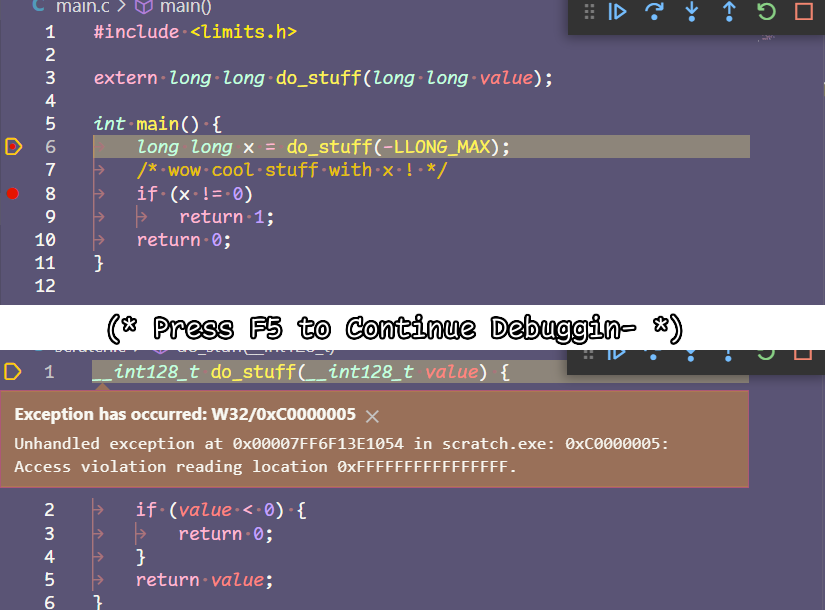

Let’s see what happens when we break ABI. Our function isn’t even that complex; the breakage is probably minor at best! So, here’s our 2 .c files:

main.c:

#include <limits.h>

extern long long do_stuff(long long value);

int main() {

long long x = do_stuff(-LLONG_MAX);

/* wow cool stuff with x ! */

if (x != 0)

return 1;

return 0;

}

do_stuff.c:

__int128_t do_stuff(__int128_t value) {

if (value < 0) {

return 0;

}

return value;

}

Now, let’s build it, with Clang + MSVC using some default debug flags:

[build] [1/2 0% :: 0.009] Re-checking globbed directories...

[build] [2/3 33% :: 0.097] Building C object CMakeFiles/scratch.dir/do_stuff.c.obj

[build] [2/3 66% :: 0.099] Building C object CMakeFiles/scratch.dir/main.c.obj

[build] [3/3 100% :: 0.688] Linking C executable scratch.exe

[build] Build finished with exit code 0

We’ll note that, despite the definition having different types from the declaration, not hiding it behind a DLL, and not doing any other shenanigans to hide the object file that creates the definition from its place of declaration, the linker’s attitude to us having completely incompatible declarations and definitions is pretty clear:

But! Even if the linker’s fields are barren, assuredly it’s not so bad, rig—

Oh. …

…

Oh.

Okay, so in C we can break ABI just by having the wrong types on a function and not matching it up with a declaration. The linker genuinely doesn’t care about types or any of that nonsense. If the symbol do_stuff exists, it will bind to the symbol do_stuff. Doesn’t matter if the function signature is completely wrong: by the time we get to the linker step — and more importantly, to the actual run-my-executable step — “types” and “safety” are just things for losers. It’s undefined behavior, you messed up, time for you to take a spill and get completely wrecked. Of course, every single person is looking at this and just laughing right now. I mean, come on! This is rookie nonsense, who defines a function in a source file, doesn’t put it in a header, and doesn’t share it so that the front end of a compiler can catch it?! That’s just some silliness, right? Well, what if I told you I could put the function in a header and it still broke?

What if I told you this exact problem could happen, even if the header’s code read extern long long do_stuff(long long value);, and the implementation file had the right declaration and looked fine too?

Causing Problems (By Accident)

See, the whole point of ABI breaks is they can happen without the frontend or the linker complaining. It’s not just about headers and source files. We have an new entirely source of problems, and they’re called Libraries. As shown, C does not mangle its identifiers. What you call it in the source code is more or less what you get in the assembly, modulo any implementation-specific shenanigans you get into. This means that when it comes to sharing libraries, everybody has to agree and shake hands on exactly the symbols that are in said library.

This is never more clear than on *nix distributions. Only a handful of people stand between each distribution and its horrible collapse. The only reason many of these systems continue to work is because we take these tiny handful of people and put them under computational constraints that’d make Digital Atlas not only shrug, but yeet the sky and heavens into the void. See, these people - the Packagers, Release Managers, and Maintainers for anyone’s given choice of system configuration — have the enviable job of making sure your dynamic libraries match up with the expectations the entire system has for them. Upgraded dynamic libraries pushed to your favorite places — like the apt repositories, the yum repositories, or the Pacman locations — need to maintain backwards compatibility. Every single package on the system has to use the agreed upon libc, not at the source level,

but at the binary level.

My little sample above? I was lucky: I built on debug mode and got a nice little error popup and something nice. Try doing that with release software on a critical system component. Maybe you get a segmentation fault at the right time. If you’re lucky, you’ll get a core dump that actually gives some hint as to what’s exploded. But most of the time, the schism happens far away from where the real problem is. After all, instead of giving an exception it could just mess with the wrong registers, or destroy the wrong bit of memory, or overwrite the wrong pieces of your stack. It’s unpredictable how it will eventually manifest because it works at a level so deeply ingrained and based on tons of assumptions that are completely invisible to the normal source code developer.

When there are Shared Libraries on the system, there are two sources of truth. The one you compile your application against - the header and its exported interfaces - and the shared library, which actually has the symbols and implementation. If you compile against the wrong headers, you don’t get warned that you have the wrong definition of this or that. It just assumes that things with the same name behave in the expected fashion. A lot of things go straight to hell. So much so that it can delay the adoption of useful, necessary features.

Usually by ten to eleven years:

- C99 introduced

_Complexand Variable Length Arrays. They are now optional, and were made that way in C11. (About 12 years.) - ~10% of the userbase is still using Python 2.x in 2019. Python 3 shipped first around 2008. (About 11 years.)

- C++11

std::string: banned copy-on-write first in 2008 (potentially finalized the decision in 2010, I wasn’t Committee-ing at that time). Linux distributions using GCC and libstdc++ as their central C++ library finally turned it on in 2018/19. (About 10 years.)

And That’s the Good Ending

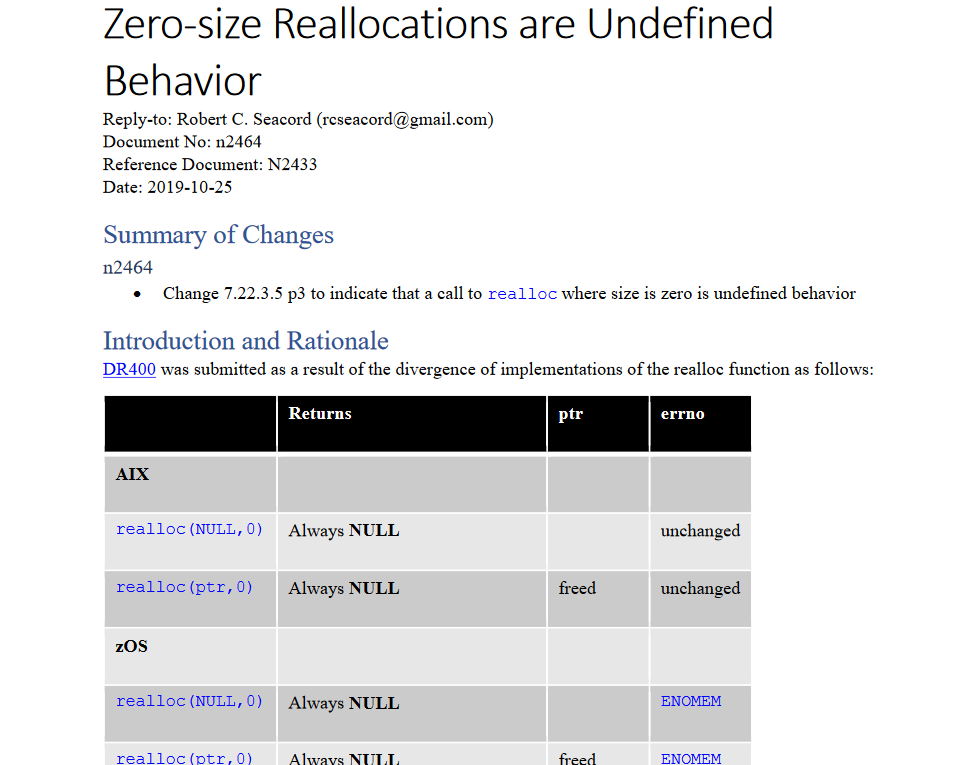

Remember, that’s C++. You know, the language with the “ambitious” Committee that C and Game Developers like to routinely talk smack about (sometimes for really good reasons, and sometimes for pretty bad reasons). The bad ending you can get if you can’t work out a compatibility story is that conservative groups - say, the C Committee - will just blow everything up. For example, when the C Committee first learned that realloc on many implementations had diverging behavior, they tried to fix it by releasing Defect Report (DR) 400. Unfortunately, DR 400 still didn’t close the implementation-defined behavior loop for realloc of size 0. After quite a few more years implementing it, then arguing about it, then trying to talk to implementations, this paper showed up:

You would think adding more undefined behavior to the C Standard would be a bad thing, especially when it was defined before. Unfortunately, implementations diverged and they wanted to stay diverged. Nobody was willing to change their behavior after DR 400. So, of course,

N2464 was voted in unanimously to C23.

In reality, almost everyone on the C Committee is an implementer. Whether it’s of a static analysis product, security-critical implementations and guidelines, a (widely available) shipping standard library, an embedded compiler, or Linux kernel expertise, there are no greenfield individuals. This is when it became clear that the Standard is not the manifestation of a mandate from on-high, passed down to implementations. Rather, implementations were the ones who dictated everything about what could and could not happen in the C Standard. If any implementation was upset enough about a thing happening, it would not be so.

But… ABI?

If you read my last article, on ABI, then this is just another spin on exactly what almost happened to Victor Zverovich’s fmtlib between C++20 and C++23. Threatening intentional non-conformance due to not wanting to / not needing to change behavior is a powerful weapon against any Committee. While the fmtlib story had a happier ending, this story doesn’t. realloc with size of 0 is undefined behavior now, plain and simple, and each implementation will continue to hold the other implementations — and us users — at gunpoint. You don’t get reliable behavior out of your systems, implementations don’t ever have to change (and actively resist such changes), and the standards Committee remains enslaved to implementations.

This means that the Committee generally does not make changes which implementations, even if they have the means to follow, would be deemed too expensive or that they do not want to. That’s the Catch-22. It’s come up a lot in many discussions, especially around intmax_t or other parts of the standard. “Well, implementations are stuck at 64-bits because it exists in some function interfaces, so we can’t ever change it.” “Well, we can’t change the return value for these bool-like functions because that changes the registers used.” “So, Annex K is unimplementable on Microsoft because we swapped what the void* parameters in the callback mean, and if Microsoft tries to change it to conform to the Standard, we are absolutely ruined.” And so on, and so forth.

But, there is a way out on a few platforms. In fact, this article isn’t about just how bad ABI is,

but how to fix at least one part of it, permanently.

An Old Solution

Any robust C library that is made to work as a system distribution, is already deploying this technique. In fact, if you’re using glibc, musl libc, and quite a few more standard distributions, they can already be made to increase their intmax_t to a higher number without actually disturbing existing applications. The secret comes from an old technique that’s been in use with NetBSD for over 25 years: assembly labels.

The link there explains it fairly succinctly, but this allows an implementation to, effectively, rename the symbol that ends up in the binary, without changing your top level code. That is, given this code:

extern int f(void) __asm__("meow");

int f (void) {

return 1;

}

int main () {

return f();

}

You may end up with assembly that looks like this:

meow:

mov eax, 1

ret

main:

jmp meow

Notice that the symbol name f appears nowhere, despite being the name of the function itself and what we call inside of main. What this gives us is the tried-and-true Donald Knuth style of solving problems in computer science: it adds a layer of indirection between what you’re writing, and what actually gets compiled. As shown from NetBSD’s symbol versioning tricks, this is not news: any slightly large operating system has been dealing with ABI stability challenges since their inception. In fact, there are tons of different ways implementations use and spell this:

- Microsoft Visual C:

#pragma comment(linker, "/export:NormalName=_BinarySymbolName") - Oracle C:

#pragma redefine_extname NormalName _BinarySymbolName - GCC, Arm Keil, and similar C implementations:

Ret NormalName (Arg, Args...) __attribute__((alias("_BinarySymbolName")))

All of them have slightly different requirements and semantics, but boil down to the same goal. It replaces the NormalName at compilation (translation) time with _BinarySymbolName, optionally performing some amount of type/entity checking during compilation to prevent connecting to things that do not exist to the compiler’s view (alias works this way in particular, while the others will happily do not checking and link to oblivion). These annotations make it possible to “redirect” a given declaration from its original name to another name. It’s used in many standard libray distributions, including musl libc. For example, using this weak_alias macro and the __typeof functionality, musl redeclares several different kinds of names and links them to specifically-versioned symbols within its own binary to satisfy glibc compatibility:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdarg.h>

int fscanf(FILE *restrict f, const char *restrict fmt, ...)

{

int ret;

va_list ap;

va_start(ap, fmt);

ret = vfscanf(f, fmt, ap);

va_end(ap);

return ret;

}

weak_alias(fscanf, __isoc99_fscanf);

Here, they are using it for compatibility purposes - presenting exactly this symbol name in their binary for the purposes of ABI compatibility with glibc - which begs the question…

why not use it to solve the ABI problem?

If the problem we have in our binaries is that C code built an eon ago expects a very specific symbol name mapped to a particular in-language name, what if we provided a layer of indirection between the symbol name and the in-C-language name? What if we had a Standard-blessed way to provide that layer of indirection? Well, I’m happy to say we don’t have to get academic or theoretical about the subject because I put my hands to the keyboard and figured it out. That’s right,

I developed and tested a solution that works on all 3 major operating system distributions.

Transparent Aliases

The paper document that describes the work done here is N2901. It contains much of the same statement of the problem that is found in this post, but talks about the development of a solution. In short, what we develop here is a way to provide a symbol that does officially exist as far as the final binary is concerned, much like how the asm("new_name") and __attribute__((alias("old_name"))) are. Notably, the design has these goals:

- it must cost nothing to use;

- it must cost nothing if there is no use of the feature;

- and, it must not introduce a new function or symbol.

Let’s dive in to how we build and specify something like this.

Zero-Cost (Seriously, We Mean It™ This Time)

Now, if you’ve been reading any of my posts you know that the C Standard loves this thing called “quality of implementation”, or QoI. See, there’s a rule called the “as-if” rule that, so long as the observable behavior of a program (“observable” insofar as the standard provides assurances) is identical, an implementation can commit whatever actions it wants. The idea behind this is that a wide variety of implementations and implementation strategies can be used to get certain work done.

The reality is that known-terrible implementations and poor implementation choices get to live in-perpetuity.

Is a compiler allocating something on the heap when the size is predictable and it could be on the stack instead? QoI. Does your nested function implementation mark your stack as executable code rather than dynamic allocation to save space, opening you up to some nasty security vulnerabilities when some buffer overflows get into the mix? QoI. Does what is VERY CLEARLY a set of integer operations meant to be a rotate left not get optimized into a single rotl assembly instruction, despite all the ways you attempt to cajole the code to make the compiler do that?

Quality of Implementation.

Suffice to say, there are a lot of things developers want out of their compilers that they sometimes do and don’t get, and the standard leaves plenty of room for those kind of shenanigans. In both developing and standardizing this solution, there must be no room to allow for an implementation to do the wrong thing. Implementation divergence is already a plague amongst people writing cross-platform code, and allowing for a (too) wide a variety of potentially poor implementations helps nobody.

Thusly, when writing the specification for this, we tried to stick as close to “typedefs, but for functions” as possible. That is, typedef already has all the qualities we want for this feature:

- it costs nothing to use (“it’s just an alias for another type”);

- it costs nothing if there is no use (“just use the type directly if you’re sure”);

- and, it does not introduce a new symbol (e.g.

typedef int int32_t;,int32_tdoes not show up in C or C++ binaries (modulo special flags and mapping shenanigans for better debugging experiences)).

Thusly, the goal here to achieve all of that for typedefs. Because there was such strong existing practice amongst MSVC, Oracle, Clang, GCC, TCC, Arm Keil, and several other platforms, it made it simple to not only write the specification for this, but to implement it in Clang. Here’s an example, using the proposed syntax for N2901:

int f(int x) { return x; }

// Proposed: Transparent Aliases

_Alias g = f;

int main () {

return g(1);

}

You’ll see from the generated compiler assembly, that there is no mention of “g” here, with optimizations on OR off! Here is the -O0 (no optimizations) assembly:

f: # @f

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov dword ptr [rbp - 4], edi

mov eax, dword ptr [rbp - 4]

pop rbp

ret

main: # @main

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 16

mov dword ptr [rbp - 4], 0

mov edi, 1

call f

add rsp, 16

pop rbp

ret

And the -O3 (optimizations, including the dangerous ones) assembly:

f: # @f

mov eax, edi

ret

main: # @main

mov eax, 1

ret

Now, could a compiler be hostile enough to implement it the worst possible way? Yes, sure, but having an existence proof and writing a specification that strictly conforms to the same kind of transparency allows most non-asshole compiler vendors to do the simple (and correct) thing for the featureset. But why does this work? How does it solve our ABI problem?

An Indirection Layer

Remember, the core problem with Application Binary Interfaces is that it strongly ties the name of a symbol in your final binary with a given set of semantics. Those semantics - calling convention, register usage, stack space, and even some behaviors - all inform a singular and ultimately unbreakable set of assumptions when code is compiled against a given interface. If you want to change the semantics of a symbol, then, you must change the name of the symbol. If you imagine for a second that our very important ABI symbol has the name f in our code, what we’re aiming to do is to provide a way for new code to access new behaviors and semantics using the same name - f - without tying it to behaviors locked into the ABI.

Transparent Aliases are the way to separate the two.

You can provide multiple “internal” (implementation-specific) names in your library for a given function, and then “pick” the right one based on user interaction (e.g., a macro definition). Here’s an example:

extern float __do_work_v0 (float val) { return val; }

extern float __get_work_value_v0 (void) { return 1.5f; }

extern double __do_work_v1 (double val) { return val; }

extern double __get_work_value_v1 (void) { return 2.4; }

#if VERSION_0

typedef float work_t;

_Alias do_work = __do_work_v0;

_Alias get_work_value = __get_work_value_v0;

#else /* ^^^^ VERSION_0 | VERSION_1 or better vvvv */

typedef double work_t;

_Alias do_work = __do_work_v1;

_Alias get_work_value = __get_work_value_v1;

#endif

int main () {

work_t v = (work_t)get_work_value();

work_t answer = do_work(v);

return (int)answer;

}

And, if we check out the assembly for this:

__do_work_v0: # @__do_work_v0

ret

.LCPI1_0:

.long 0x3fc00000 # float 1.5

__get_work_value_v0: # @__get_work_value_v0

movss xmm0, dword ptr [rip + .LCPI1_0] # xmm0 = mem[0],zero,zero,zero

ret

__do_work_v1: # @__do_work_v1

ret

.LCPI3_0:

.quad 0x4003333333333333 # double 2.3999999999999999

__get_work_value_v1: # @__get_work_value_v1

movsd xmm0, qword ptr [rip + .LCPI3_0] # xmm0 = mem[0],zero

ret

main: # @main

mov eax, 2

ret

You’ll notice that all the functions we wrote implementations for are present. And, more importantly, the symbols do_work or get_work_value do not appear in the final assembly. A person could compile their top-level application against our code, and depending on the VERSION_0 macro provide different interfaces (and implementations!) for the code. Note that this means that someone can seamlessly upgrade newly-compiled code to use new semantics, new types, better behaviors, and more without jeopardizing old consumers: the program will always contain the “old” definitions (…_v0), until the maintainer decides that it’s time to remove them. (If you’re a C developer, the answer to that question is typically “lol, never, next question nerd”.)

The True Goal

Most important in this process is that, so long as the end-user is doing things consistent with the described guarantees of the types and functions, their code can be upgraded for free, with no disturbance in the wider ecosystem at-large. Without a feature like this in Standard C, it’s not so much that implementations are incapable of doing some kind of upgrade. After all, asm("label"), pragma exports, __attribute((alias(old_label))), and similar all offered this functionality. But the core problem was that because there was no shared, agreed way to solve this problem, implementations that refused to implement any form of this could show up to the C Standards Committee and be well within their rights to give improvements to old interfaces a giant middle finger. This meant that the entire ecosystem suffered indefinitely, and that each vendor would have to - independently of one another - make improvements. If an implementation made a suboptimal choice, and the compiler vendor did not hand them this feature, well. Tough noodles, you and yours get to be stuck in a shitty world from now until the end of eternity.

This also has knock-on effects, of course. intmax_t does not have many important library functions in it, but it’s unfortunately also tied up to things like the preprocessor. All numeric expressions in the preprocessor are treated and computed under intmax_t. Did you want to use 128-bit integers in your code? That’s a shame, intmax_t is locked to a 64-bit number, and so a strictly-conforming compiler can take a shovel and bash your code’s skull in if you try to write a literal value that’s bigger than UINT64_MAX.

Every time, in the Committee, that we’ve tried to have the conversation for weaning ourselves off of things like intmax_t we’ve always had problems, particularly due to ABI and the fixed nature of the typedef thanks to said ABI. When someone proposes just pinning it down strictly to be unsigned long long and coming up with other stuff, people get annoyed. They say “No, I wrote code expecting that my intmax_t will grow to keep being the largest integer type for my code, it’s not fair I get stuck with a 64-bit number when I was using it properly”. The argument spins on itself, and we get nowhere because we cannot form enough consensus as a Committee to move past the various issues.

So, well, can this solve the problem?

Since we have the working feature and a compiler on Godbolt.org that implements the thing (the “thephd.dev” version of Clang), let’s try to put this to the test. Can it solve our ABI problems on any of the Big Platforms™? Let’s set up a whole test, and attempt to recreate the problems we have on implementations where we pin a specific symbol name to a shared library, and then attempt to fix that binary. The prerequisites for doing this is building the entire Clang compiler with our modifications, but that’s the burden of proof every proposal author has these days to satisfy the C Standard Committee, anyways!

The ABI Test: maxabs

We talked about how intmax_t can’t be changed because some binary, somewhere, would lose its mind and use the wrong calling convention / return convention if we changed from e.g. long long (64-bit integer) to __int128_t (128-bit integer). But is there a way that - if the code opted into it or something - we could upgrade the function calls for newer applications while leaving the older applications intact? Let’s craft some code that test the idea that Transparent Aliases can help with ABI.

Making a Shared Library

Our shared library, which we’ll just call my_libc for now, will be very simple. It’s going to have a function that computes the absolute value of a number, whose type is going to be of intmax_t. First, we need to get some boilerplate out of the way. We’ll put this in a typical <my_libc/defs.h> header file:

#ifndef MY_LIBC_DEFS_H

#define MY_LIBC_DEFS_H

#if defined(_MSC_VER)

#define WEAK_DECL

#if defined(MY_LIBC_BUILDING)

#define DLL_FUNC __declspec(dllexport)

#else

#define DLL_FUNC __declspec(dllimport)

#endif

#else

#define WEAK_DECL __attribute__((weak))

#if defined(_WIN32)

#if defined(MY_LIBC_BUILDING)

#define DLL_FUNC __attribute__(dllexport)

#else

#define DLL_FUNC __attribute__(dllimport)

#endif

#else

#define DLL_FUNC __attribute__((visibility("default")))

#endif

#endif

#if (defined(OLD_CODE) && (OLD_CODE != 0)) || \

(!defined(NEW_CODE) || (NEW_CODE == 0))

#define MY_LIBC_NEW_CODE 0

#else

#define MY_LIBC_NEW_CODE 1

#endif

#endif

This is the entire definition file. The most complicated part is working on Windows vs. Everywhere Else™, for the DLL export/import and/or the visibility settings for symbols in GCC/Clang/etc. With that out of the way, let’s create the declarations in <my_libc/maxabs.h> for our code:

#ifndef MY_LIBC_MAXABS_H

#define MY_LIBC_MAXABS_H

#include <my_libc/defs.h>

extern DLL_FUNC int my_libc_magic_number (void);

#if (MY_LIBC_NEW_CODE == 0)

extern DLL_FUNC long long maxabs(long long value) WEAK_DECL;

typedef long long intmax_t;

#else

extern DLL_FUNC __int128_t __libc_maxabs_v1(__int128_t value) WEAK_DECL;

typedef __int128_t intmax_t;

_Alias maxabs = __libc_maxabs_v1; // Alias, for the new code, here!

#endif

#endif

We only want one maxabs visible depending on the code we have. The first block of code represents the code when we are in the original DLL. It just uses a plain function call, like most libraries would in this day and age. In the new code for the new DLL, we use a new function declaration, coupled with an alias. The concrete function declarations are also marked as a WEAK_DECL. This has absolutely no bearing on what we’re trying to do here, but we have to keep the code as strongly similar/identical to real-world code as possible, otherwise our examples are bogus. We’ll see how this helps us achieve our goal in a brief moment. We pair this header file with:

- one

maxabs.cfile for the original DLL that uses the old code; - and, both

maxabs.candmaxabs.new.csource files for the new DLL.

Here is the maxabs.c file:

#include <my_libc/defs.h>

extern DLL_FUNC int my_libc_magic_number (void) {

#if (MY_LIBC_NEW_CODE == 0)

return 0;

#else

return 1;

#endif

}

// always present

extern DLL_FUNC long long maxabs(long long __value) {

if (__value < 0) {

__value = -__value;

}

return __value;

}

When we compile this into the original my_libc.dll, we can inspect its symbols. Here’s what that looks like on Windows:

Microsoft (R) COFF/PE Dumper Version 14.31.31104.0

Copyright (C) Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

Dump of file abi\old\my_libc.dll

File Type: DLL

Section contains the following exports for my_libc.dll

00000000 characteristics

0 time date stamp

0.00 version

0 ordinal base

3 number of functions

2 number of names

ordinal hint RVA name

1 0 00001010 maxabs = maxabs

2 1 00001000 my_libc_magic_number = my_libc_magic_number

The other source file, maxabs.new.c is the additional code that provides a new symbol:

#include <my_libc/defs.h>

// only for new DLL

#if (MY_LIBC_NEW_CODE != 0)

extern __int128_t __libc_maxabs_v1(__int128_t __value) {

if (__value < 0) {

__value = -__value;

}

return __value;

}

#endif

This source file only creates a definition for the new symbol if we’ve got the proper configuration macro on. And, when we inspect this using dumpbin.exe to check for the exported symbols, we see that the my_libc.dll in the new directory has the changes we expect:

Microsoft (R) COFF/PE Dumper Version 14.31.31104.0

Copyright (C) Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

Dump of file abi\new\my_libc.dll

File Type: DLL

Section contains the following exports for my_libc.dll

00000000 characteristics

0 time date stamp

0.00 version

0 ordinal base

4 number of functions

3 number of names

ordinal hint RVA name

1 0 00001030 __libc_maxabs_v1 = __libc_maxabs_v1

2 1 00001010 maxabs = maxabs

3 2 00001000 my_libc_magic_number = my_libc_magic_number

Note, very specifically, that the old maxabs function is still there. This is because we marked its definition in the maxabs.c source file as both extern and DLL_FUNC (to be exported). But, critically, it is not the same as the alias. Remember, when the compiler sees _Alias maxabs = __libc_maxabs_v1;, it simply produces a “typedef” of the function __libc_maxabs_v1. All code that then uses maxabs, as it did before, will just have the function call transparently redirected to use the new symbol. This is the most important part of this feature: it is not that it should be a transparent alias to the desired symbol. It is that it must be, so that we have a way to transition old code like the one above to the new code. But, speaking of that transition… now we need to check if this can work in the wild. If you do a drop-in replacement of the old libc, do old applications - that cannot/will not be recompiled - still use the old symbols despite having the new DLL and its shiny new symbols present? Let’s make our applications, and find out.

The “Applications”

We need some source code for the applications. Nothing terribly complicated, just something to use the code (through our shared library) and prove that, if we swap the DLL out from under the application, it continues to work as if we’ve broken nothing. So, here’s an “app”:

#include <my_libc/maxabs.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

intmax_t abi_is_hard = -(intmax_t)sizeof(intmax_t);

intmax_t but_not_that_hard = maxabs(abi_is_hard);

printf("%d\n", my_libc_magic_number());

return (but_not_that_hard == ((intmax_t)sizeof(intmax_t))) ? 0 : 1;

}

We use a negated sizeof(intmax_t) since, for all the platforms we will test on, we have 2’s complement integers. This flips most of the bits in the integers to represent the small negative value. If something terrible happens - for example, some registers are not properly used because we created an ABI break - then we’ll see that reflected in the result even if we build with optimizations on and no stack protections (-O3 (GCC, Clang, etc.) or -O2 -Ob2 (MSVC)). Passing that value to the function and not having the expected positively-sized result is a fairly solid, standards-compliant check.

We also print out the magic number, to get a “true” determination of which shared library we are linked against at runtime (since it uses the same function name with no aliasing, we should see 0 for the old library and 1 for the new library, regardless of whether it’s the old application or the new application.)

Using the single app.c code above, we create 3 executables:

- Application that was created with

OLD_CODEdefined, and is linked with theOLD_CODE-defined shared library. It represents today's applications, and the "status quo" of things that come packaged with your system today. - Application that was created with

NEW_CODEdefined, and is linked to a shared library built withNEW_CODEdefined. This represents tomorrow's applications, which build "cleanly" in the new world of code. - Application that was created with

OLD_CODEdefined, but is linked to a shared library built withNEW_CODE. This represents today's applications, linked against tomorrow's shared library (e.g., a partial upgrade from "apt" that does not re-compile the world for a new library).

Of importance is case #2. This is the case we have trouble with today and what allows implementations to come to WG14 Standard Meetings and block any kind of progress regarding intmax_t or any other “ABI Breaking” subjects today. So, for Application #0, we compile with #define OLD_CODE on for the whole build. For Application #1, we compile with #define NEW_CODE on for the whole build.

For Application #2, we don’t actually compile anything. We create a new directory and place the old application (from #0) and the new DLL (from #1) in the same folder. This triggers what is known as “app local deployment”, and the DLL in the local directory for the application will be picked up by the system’s application loader. This also works on OSX and Linux, provided you modify the RPATH linker setting to include the extremely special string ${ORIGIN}, exactly like that, uninterpreted. (Which is a little harder to do in CMake, unless the special raw string [=[this will be used literally]=] syntax is used.)

It took a while, but I’ve effectively mocked this up in a CMake Project to make sure that Transparent Aliases worked (GitHub Link). It took a few tries to set it up properly, but after setting up the CMake, the tests, and verifying the integrity of the bits, I checked several operating systems. Here’s the output on…

Windows:

transparent-aliases> abi\old\app_old.lib_old.exe

0

transparent-aliases> $LASTEXITCODE

0

transparent-aliases> abi\new\app_new.lib_new.exe

1

transparent-aliases> $LASTEXITCODE

0

transparent-aliases> abi\new\app_old.lib_old.exe

1

transparent-aliases> $LASTEXITCODE

0

and, on Ubuntu:

> ./abi/old/app_old.lib_old

0

> $?

0

> ./abi/new/app_new.lib_new

1

> $?

0

> ./abi/new/app_old.lib_old

1

> $?

0

Perfect. The return code of 0 (determined with $LASTEXITCODE in Powershell and $? in Ubuntu’s zsh) lets us know that the negative value passed into the function was successfully negated, without accidentally breaking anything (only passing half a value in a register or referring to the wrong stack location entirely). The last executable invoked from the command line corresponds to the case we discussed for #2, where we’re in the new/ directory. This directory contains the mylibc.dll/mylibc.so, and as we can see from the printed number invoked after each executable, we get the proper DLL (0 for the old one, 1 for the new one).

Thus, I have successfully synthesized a language feature in C capable of providing backwards binary compatibility with shared libraries/global symbol tables!

ez gg.

… But, unfortunately, as much as I’d like to spend the rest of this post 🎉 celebrating 🎊, it’s not all rainbows and sunshine.

No Free Lunch

Yeah, sometimes some things are too good to be true.

What I’ve proposed here does not fix all scenarios. Some of them are just the normal dependency management issues. If you build a library on top of something else that uses one of the changed types (such as intmax_t or something else), then you can’t really upgrade until your dependents do. This requirement does not exist for folks who typically compile from source, or folks who have things built tailor-made for themselves: usually, your embedded developers and your everything-must-be-a-static-library-I-can-manage types of people. For those of us in large ecosystems who have to write plugins or play nice with other applications and system libraries, we’re generally the last to get the benefits. But,

at least we’ll finally have the chance to have that discussion with our communities, rather than just being outright denied the opportunity before Day 0.

There’s also one other scenario it can’t help. Though, I don’t think anyone can help fix this one, since it’s an explicit choice Microsoft has made. Microsoft’s ABI requirements are so painfully restrictive that they not only require backwards compatibility (old symbols need to be present and retain the same behavior), but forward compatibility (you can downgrade the library and “strip” new symbols, and newly built code must still work with the downgraded shared library). The solution that the Microsoft STL has adopted is on top of having files like msvcp140.dll, whenever they need to break something they ship an entirely new DLL instead, even if it contains literally only a single object such as msvc140p_atomic_wait.dll, msvc140p_1.dll, and msvc140p_2.dll. Some of them contain almost no symbols at all, and now that they are shipped nothing can be added or removed to that list of symbols lest you break a new application that has it’s DLL swapped out with an older version somewhere. Poor msvcp140_codecvt_ids.dll is 20,344 bytes, and for all that 20 kB of space, its sole job is this:

Microsoft (R) COFF/PE Dumper Version 14.31.31104.0

Copyright (C) Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

File Type: DLL

Section contains the following exports for MSVCP140_CODECVT_IDS.dll

00000000 characteristics

E13307D2 time date stamp

0.00 version

1 ordinal base

4 number of functions

4 number of names

ordinal hint RVA name

1 0 00003058 ?id@?$codecvt@_SDU_Mbstatet@@@std@@2V0locale@2@A

2 1 00003040 ?id@?$codecvt@_S_QU_Mbstatet@@@std@@2V0locale@2@A

3 2 00003050 ?id@?$codecvt@_UDU_Mbstatet@@@std@@2V0locale@2@A

4 3 00003048 ?id@?$codecvt@_U_QU_Mbstatet@@@std@@2V0locale@2@A

Whenever they need a new symbol — even if it’s more codecvt IDs — they can’t just slip it into this relatively sparse DLL: it has to go into an entirely different DLL altogether before being locked into stability from now until the heat death of the Windows ecosystem. Transparent Aliases can’t save Windows from this kind of design choice because Transparent Aliases are predated on the idea that you can add new symbols, exports, and whatever else to the dynamic library without doing anything to the old ones. But, hey: if Microsoft wants to take RedHat’s ABI stability and Turn It Up To 11, who am I to argue with the 🤑 Billions 🤑 they’re raking in on a yearly basis? Suffice to say, if they ever change their mind, at least Transparent Aliases would be capable of solving their current Annex K predicament! That is, they have a different order for the void* parameters that are the userdata pointer. Like, as currently exists, Microsoft’s bsearch_s:

void* bsearch_s(const void *key, const void *base,

size_t number, size_t width,

// Microsoft:

int (*compare) (void* userdata, const void* key, const void* value),

void* userdata

);

void* bsearch_s(const void *key, const void *base,

size_t number, size_t width,

// Standard C, Annex K:

int (*compare) (const void* key, const void* value, void* userdata),

void* userdata

);

It’s one of the key reasons Microsoft can’t fully conform to Annex K, and why the code isn’t portable between the platforms that do have it implemented. With Transparent Aliases, a platform in a similar position to Microsoft can write a new version of this going forward:

void* bsearch_s_annex_k(const void *key, const void *base,

size_t number, size_t width,

int (*compare) (const void* key, const void* value, void* userdata),

void* userdata

);

void* bsearch_s_msvc(const void *key, const void *base,

size_t number, size_t width,

int (*compare) (void* userdata, const void* key, const void* value),

void* userdata

);

#if defined(_CRT_SECURE_STANDARD_CONFORMING) && (_CRT_SECURE_STANDARD_CONFORMING != 0)

_Alias bsearch_s = bsearch_s_annex_k;

#else

_Alias bsearch_s = bsearch_s_msvc;

#endif

This would allow MSVC to keep backwards compatibility in old DLLs, while offering standards-conforming functionality in newer ones. Of course, because of the rule that they can’t change existing DLL’s exports, there’s no drop-in replacement. A new DLL has to be written containing these symbols, and code wishing to take advantage of this has to re-compile anyways.

But, at least there may be a way out, if they so choose, in the future if they perhaps relax some of their die-hard ABI requirements. Still, given the demo above and the it-would-work-if-they-did-not-place-these-limitations-on-themselves-or-just-shipped-a-new-DLL nature of things, I would consider this…

A Great Success

No longer a theoretical idea, this is an existence proof that we can create backwards-compatible shared libraries on multiple different platforms that allow for seamless upgrading. A layer of indirection between the name the C code sees and uses for its functions versus what the actual symbol name effectively creates a small, cross-platform, compile-time-only symbol presevation mechanism. It has no binary size penalty beyond what you, the end user, decide to use for any additional symbols you want to add to old shared libraries. No old symbols have to be messed with, solving the shared library problem. Having an upgrade path finally stops dragging along the technical liability of things chosen from well before I was even born:

Wow, Y2K wasn’t a bug; it was technical debt.

I think I’m gonna throw up.

— Misty, Senior Product Manager, Microsoft & Host of Retro Tech, March 3 2022

Our forebears are either not interested in a world without the mounting, crushing debt or just prefer not to tackle that mess right now (and may get to it Later™, maybe at the Eleventh Hour). Whether out of necessity for the current platforms, or just not wanting to sit down and really do a “recompile the world” deal, they pass this burden on to the rest of us to deal with. It gets worse, too, when you realize that many of them start to check out and retire (or just straight up burn out). This means that we, as the folks now coming to inherit this landscape, have decisions we need to be making. We can continue to deal with their problems, continue to fight with their code and implementations into 2038 and beyond, continue limiting our imagination and growth for both our standard libraries or our regular libraries for the sake of compatibility… Or.

We can actually fix it.

I’m going to hit my 30s soon. I have no desire to still be talking about time_t upgrades when I’m in my 40s and 50s, let alone arguing about why intmax_t being stuck at 64-bits is NOT fine, and how it is not NOT okay that 64-bits is the biggest natively-exposed C integer type anyone can get out of Standard C. I didn’t put up with a lifetime of suffering to deal with this in a digital world where we already control all the rules. That this is the best we can do in a place of infinite imagination just outright sucks, and having things like the C Standard stuck in 1989 over these decisions is even worse for those of us who would like to take their systems beyond what has already been done. Therefore…

I will embrace them.

I will Embrace these aging imaxabs and gmtime and other such symbols.

I will Extend their functionality and allow new implementations and new librarians able and willing to imagine a better world to alias newer programmers to the delightfully improved functionality while the old stuff hobbles along, old symbols left in their current state of untouchable decay. I will put Transparent Aliases in the C Standard and pave a way for the new.

And when the archival is done? When the old programs are properly preserved and the old guard closes their eyes, well taken care of into their last days? I will arm myself. I will make one more trip down into the depths of the Old and the Dark. I will find each and every one of the last symbols, the 32-bit and 64-bit shackles we have had to live with all these years. And to save us — to save our ABI and the to-be-imagined future — I will…

Extinguish them. 💚

Art by lilwilbug, check them out, follow them, and commission them too!

%20-%20C++%20Weekly%20270%20-%20Title%20Screen.png)