The last article checked the landscape of various C and C extension implementations of Closures for their performance capabilities. But, there were a few tweaks and extra things we could do to check the performance of other techniques. At the time, we ignored such techniques because they were so common, but it helps to quantify their performance relative to everything else, so we re-ran the benchmarks with a few new categories!

Skipping the Introductions

If you want an introduction to what is going on, there’s a gentle description with some 10,000 foot overview in the previous article. Additionally, if you’d like to learn more about specific kinds of Closures as they exist in C and/or C++, you can read a much older article or read the entire introduction in this work-in-progress C proposal. The much older article is a much gentler introduction; the work-in-progress C proposal goes through a lot of the technical and design nitty-gritty and why things work or do not work very well.

The purpose of this article will, once again, be performance and deducing the performance characteristics of various designs. Much of this was covered in the previous article, so we’re going to focus on the new additions to the Benchmarks since then and the important takeaways.

As always, the implementations of my benchmarks are publicly available1.

Experimental Setup

The only thing that changed from the last time we did this was to use 150 repetitions of the whole 100,000+ sample iterations benchmarks rather than just 50 or 100 repetitions. You can find the full, detailed explanation at the bottom of this article.

Plain C - New Categories

The new benchmarking categories reflected in the new bar graphs explicitly track the performance of a few different kinds of “Plain C” testing.

- Normal Functions: regular C functions which add an extra argument to the function call in order to pass more data. Somewhat similar in representation to rewriting

qsorttoqsort_r/qsort_sto pass a user data pointer. - Normal Functions (Rosetta Code): regular C functions which add an extra argument to the function call in order to pass more data. Taken directly from the Rosetta Code weekly, and uses a pointer

int* kto refer to an already-existing value ofkduring a series of recursive calls. - Normal Functions (Static): regular C function which uses a

staticvariable to pass the specific context to the next function. Not thread safe. Does not modify the function call signature. - Normal Functions (Thread Local): same as “Normal Functions (Static)” but using a

thread_localvariable instead of a static variable. Obviously thread safe. Does not modify the function call signature.

These are different from the “Normal Functions” in small but important ways, and – critically – two of them do not modify the signature of the function call, meaning they can be used with the old-style of qsort APIs that do not take a void* user_data parameter. In particular, rather than taking an extra or dummy argument like arg* in:

int f0(arg* unused) {

(void)unused;

return 0;

}

int f1(arg* unused) {

(void)unused;

return 1;

}

int f_1(arg* unused) {

(void)unused;

return -1;

}

It instead preserves the initial interface, without the (potentially unused) argument. This is important for Foreign Function Interfaces (FFI) and other shenanigans that gets used with closure-style code. Thus, rather than needing to write new functions with an extra argument, the return 1, return -1, and return 0 helpers can be written in the normal, plain, usual way:

int f0() {

return 0;

}

int f1() {

return 1;

}

int f_1() {

return -1;

}

One would imagine that such a change would not actually have any meaningful performance impact, and that using something like static variables or global variables to shuttle that data over into whatever function that needed it wouldn’t cause any measurable performance difference.

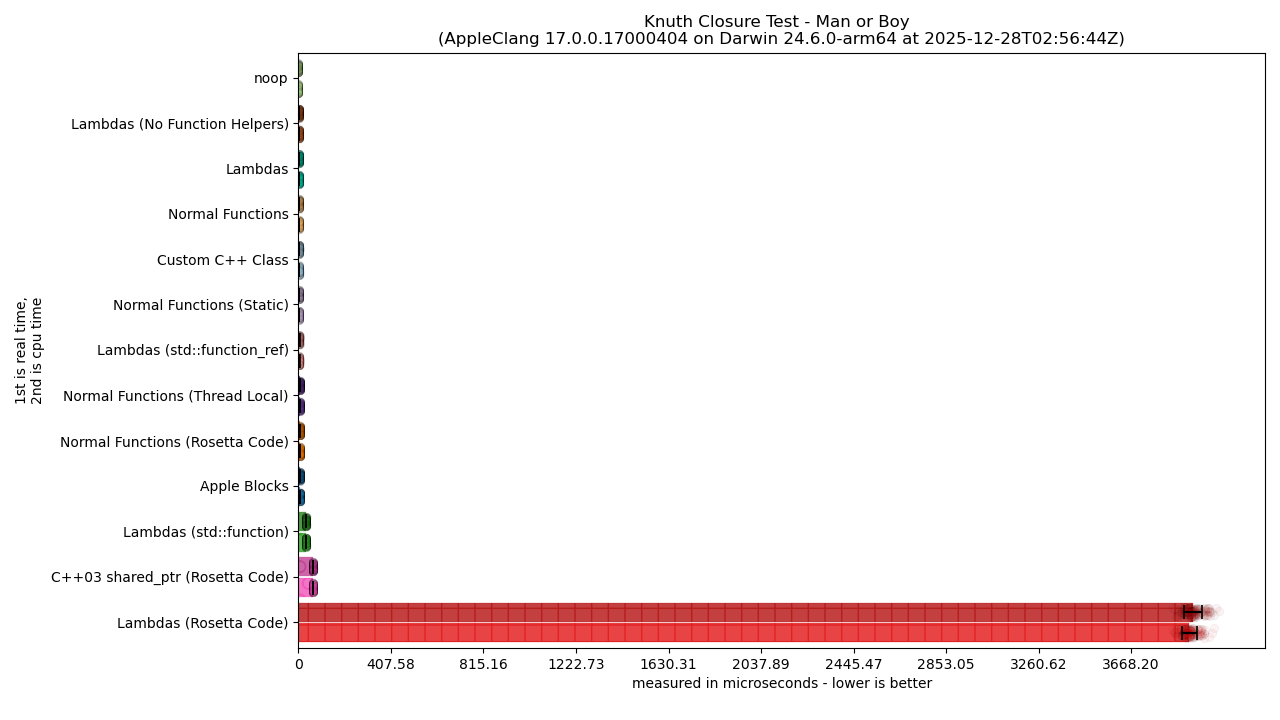

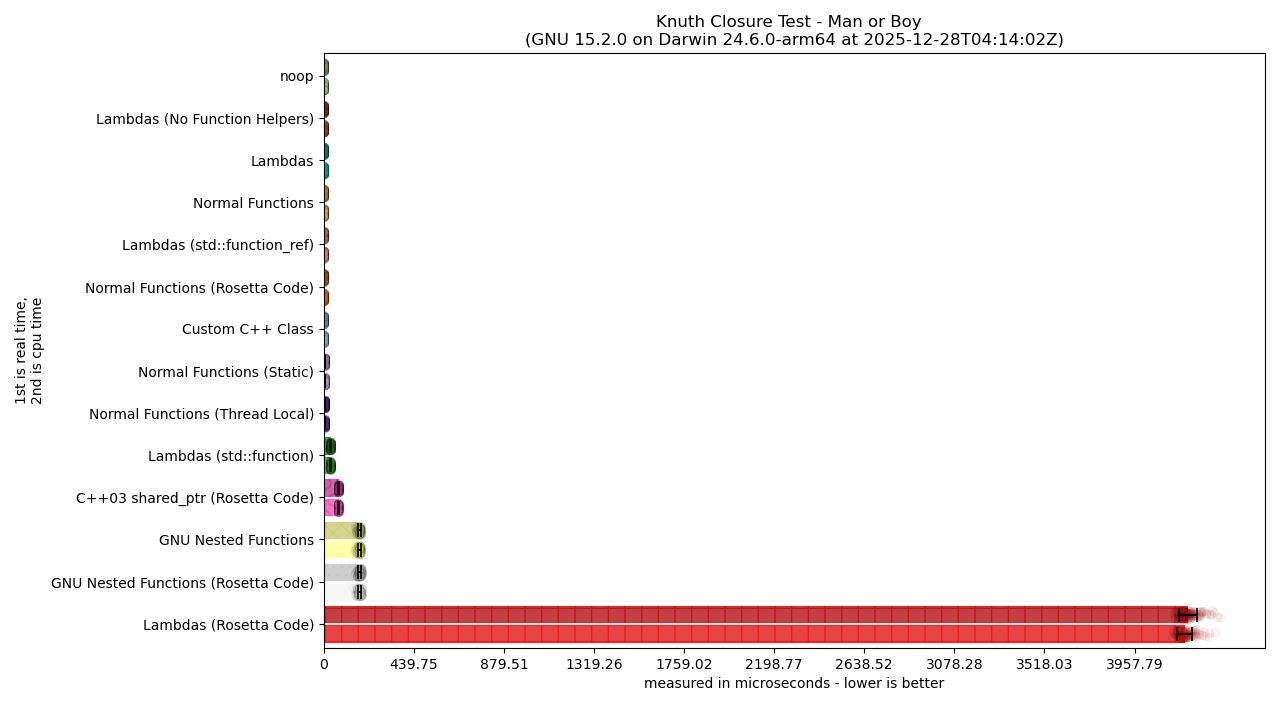

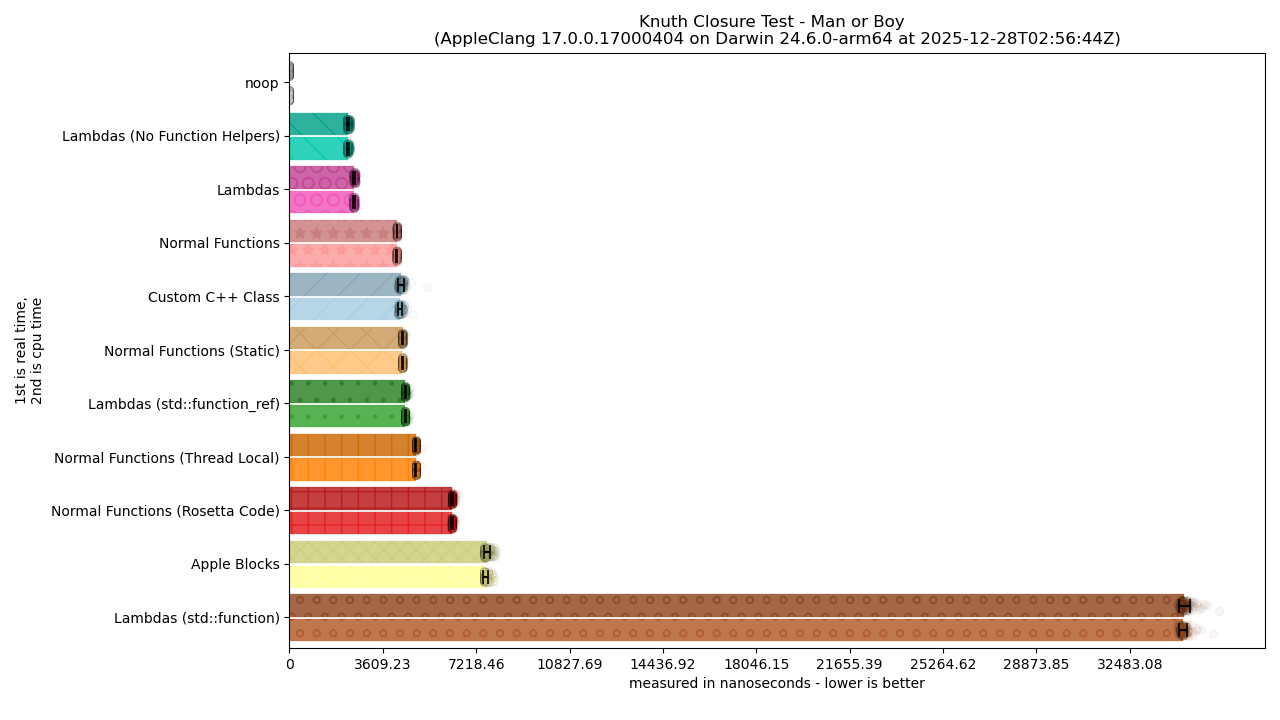

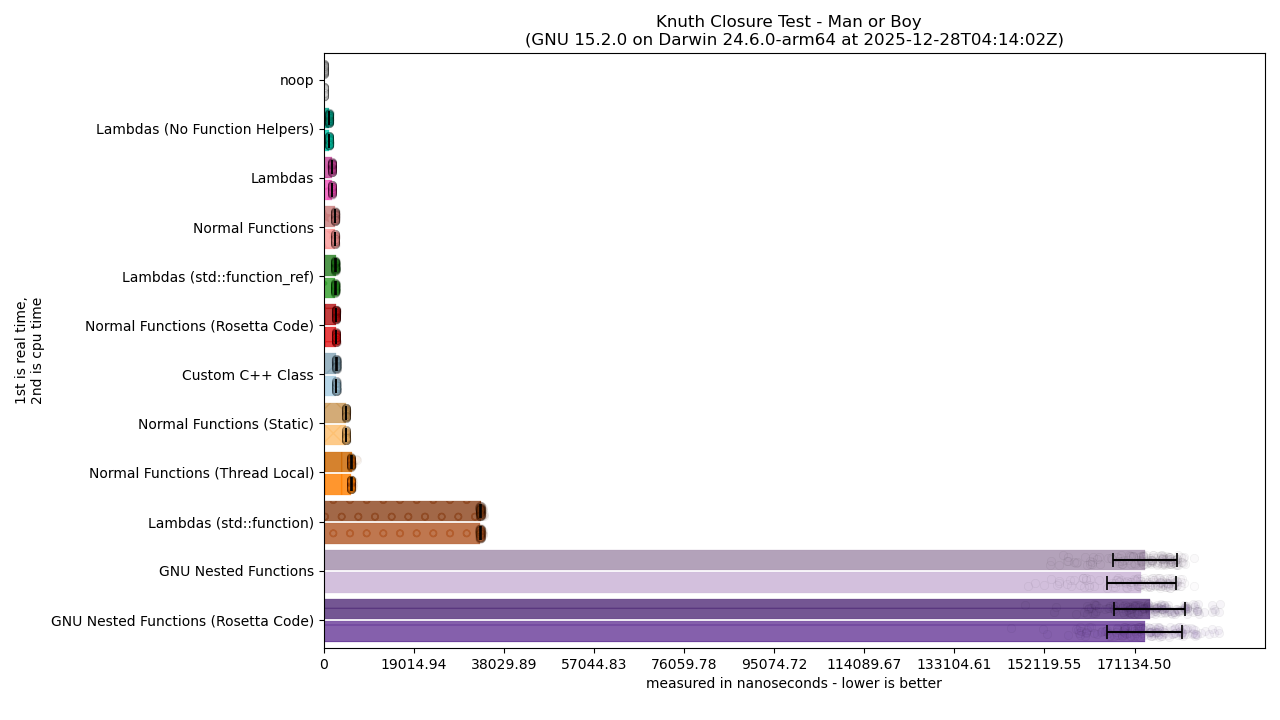

Results

Of course, if it were true that there was no performance difference, I wouldn’t be forced to write about it! So, here we are, the cost or non-cost for the various kinds of “Normal Functions” usages, as compared to all the others:

For the vision-impaired, a text description is available.

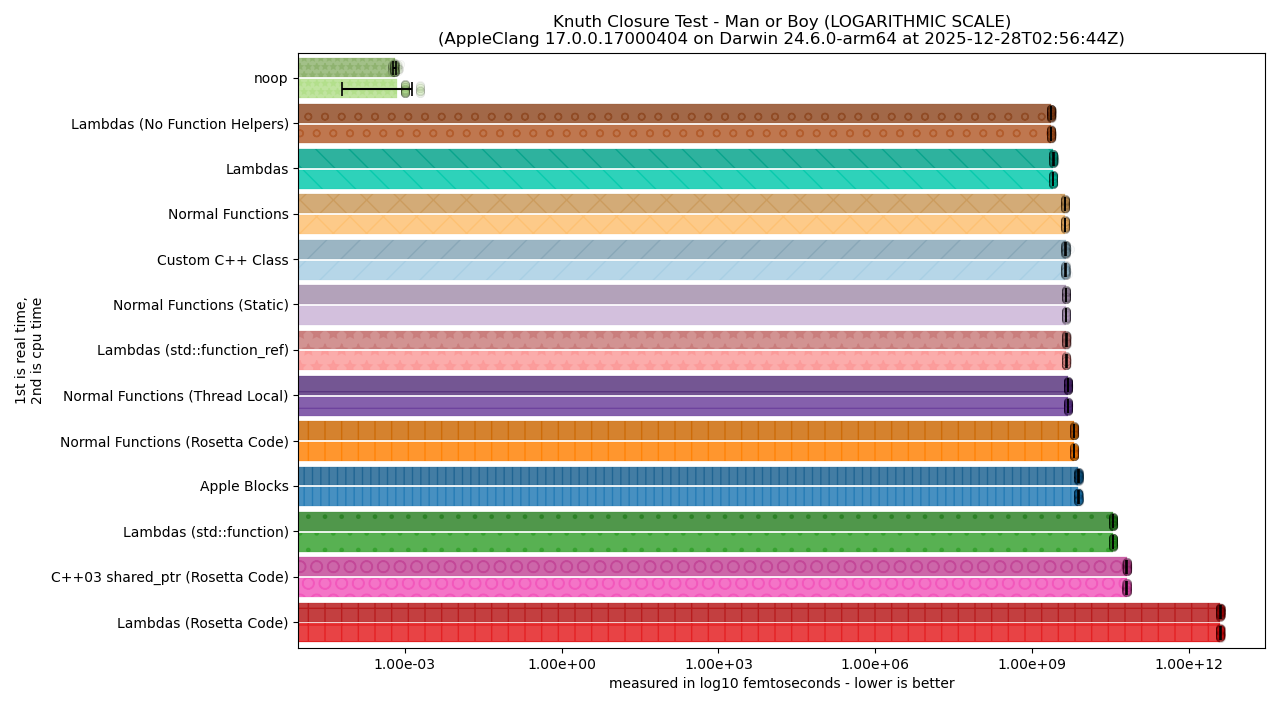

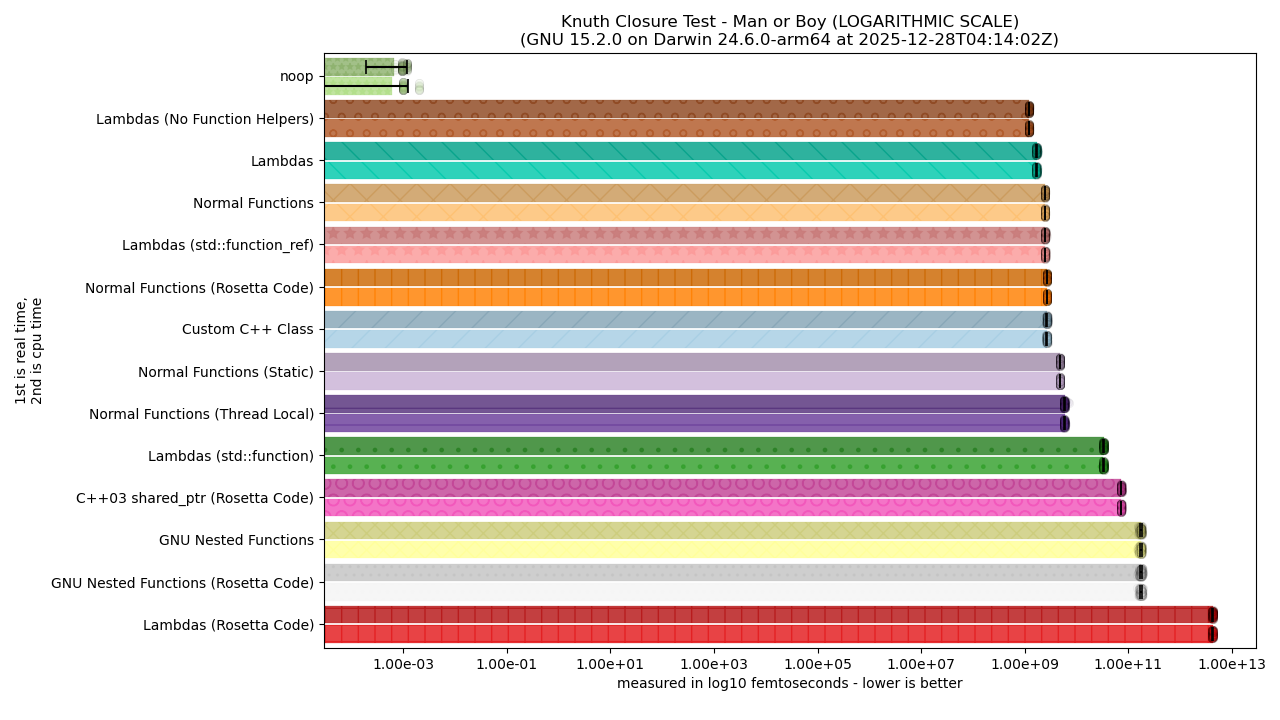

As shown in the last article, performance is SO TERRIBLE for some solutions that it completely crowds out any useful visual from the linear graphs. So, we need to swap to the logarithmic graphs to get a better picture:

For the vision-impaired, a text description is available.

Still, the logarithmic graphs render things like the black error bars on each bar graph completely useless. So, we swap back to linear this time, but with the caveat that we remove some of the worst “outliers” (e.g., the things that had the most awful performance metrics). This, effectively, means cutting out the “Lambda (Rosetta Code)” category and bar graph. This gives us the following linearly-scaled graph:

For the vision-impaired, a text description is available.

There, that’s much better and easier to read! It also gives us a more precise look at the faster-performing functions, and lets us talk about it much more clearly!

Insights

There are quite a few insights here that are important to elaborate on. We will start first with the obvious DRASTIC improvements we need from the original code contained in the previous article to where are are now: “Normal Functions (Rosetta Code)” to “Normal Functions”.

Becoming the Most Normal Function

The only difference between this and “Normal Functions (Rosetta Code)” is us not holding onto a pointer. Specifically, the all structure in the Normal Functions is just:

typedef struct all {

int (*B)(struct all*);

int k;

struct all *x1, *x2, *x3, *x4, *x5;

} all;

static int A(int k, all* x1, all* x2, all* x3, all* x4, all* x5);

static int B(all* self) {

return A(--self->k, self, self->x1, self->x2, self->x3, self->x4);

}

static int A(int k, all* x1, all* x2, all* x3, all* x4, all* x5) {

if (k <= 0) {

return x4->B(x4) + x5->B(x5);

}

else {

all y = { .B = B, .k = k, .x1 = x1, .x2 = x2, .x3 = x3, .x4 = x4, .x5 = x5 };

return B(&y);

}

}

The only change here is that instead of using int* k like in the arg structure of Rosetta Code we use int k directly:

typedef struct arg {

int (*fn)(struct arg*);

int* k;

struct arg *x1, *x2, *x3, *x4, *x5;

} arg;

static int f_1(arg* _) {

return -1;

}

static int f0(arg* _) {

return 0;

}

static int f1(arg* _) {

return 1;

}

// --- helper

static int eval(arg* a) {

return a->fn(a);

}

static int A(arg*);

// --- functions

static int B(arg* a) {

int k = *a->k -= 1;

arg args = { B, &k, a, a->x1, a->x2, a->x3, a->x4 };

return A(&args);

}

static int A(arg* a) {

return *a->k <= 0 ? eval(a->x4) + eval(a->x5) : B(a);

}

It turns out needing to do that indirect load to get at int* k cost us a LOT more than any of us could hope for. This is surprising, given that the lambda uses a single default capture of & and references the k it was made with transparently. In essence: it works actually like the poorly-performing “Normal Functions (Rosetta Code)” example, and yet the compiler is able to outperform this in comparison to the structure passed as an explicit argument.

The problem is that the indirect load through both (a) the int* k and (b) the all*/arg* structure are actually impeding compiler optimization and slowing us down. In C, we like to imagine that doing in-place modification and operations directly on a given piece of memory can generally be better and faster than other techniques. This applies for big data sets and huge arrays, but for smaller work like what is in the Man or Boy test, it’s actually the opposite: pointers to smaller pieces of data are a big waste of time.

The good news is that removing the int* k only means we have one level of indirection to deal with, and that really boosts performance compared to the original, bad Rosetta Code Wiki example that this benchmark is based on. Unfortunately, despite getting a huge boost from its old performance…

Lambdas Are Still Peak

It is the encapsulation and the preservation of type information without hiding it behind an additional structures that keeps the performance lean. This means that the design of lambdas – a unique object with its own type that is not immediately hoisted or erased like it is in Apple Blocks, GNU Nested Functions, and other compiler techniques – is actually the leanest possible implementation.

The drawback of this that is especially egregious in C, unfortunately, is that unlike C++ there are no templates in C. There’s no “fake” recursion parameter we can add to limit an infinity-spiral of self-calls. This means that unique typings – while an unrestricted boon in C++ – is actually a bit of a drawback in C! In terms of passing arguments around and returning them, there’s no type-generics at compile-time that can help with this.

So either all the code interacting with it has to be macros (EWWWW), OR we need to develop at least one layer of indirection so we can prevent things like infinite recursion or realistically handle lots of data types. The much more sadder conclusion is that a programming language like C, unless you drop down to assembly or hand-unroll loops with your own selection of manually-crafted strong types, you will lose out on some degree of performance. This is not normally something anybody would be able to say about C, but it turns out that needing to do type-erasure imposes a cost. If the compiler cannot unroll that cost for any number of reasons, you will end up paying for it in performance. (But you can still get pretty good code size, so that part is nice at least.)

The Next Tier Up: Very Small Amounts of Type Erasure

While Lambdas are the best and standalone in what they are capable of, they are only the best under C++-ish, template-ish circumstances (like C macro generics). When you have to ditch the templates and the perfect type information, C++-style Lambdas lose a good bit of their competitive edge. Primarily, any amount of lean type erasure adds an non-negotiable impact to performance over the base case, as shown by “Normal Functions”, “Custom C++ Class”, “Lambdas std::function_ref”, and “Normal Functions (Statics)”.

I put “Normal Functions (Statics)” into this group despite it clearly having very bad performance implications from how GCC implements it that actually make it slightly wore than the others. It’s also surprising that passing a variable by static variable – a solution touted by many C developers and often said to be “just as good” as being able to hijack the function signature and add a new parameter – is actually strictly worse than “Normal Functions”. One can imagine that a static variable in charge of doing transportation is inevitably going to have to pay for the cost of loads and stores for each function call, and that compilers have to try to contest with that differently.

Slightly Worse: thread_local

No surprise that no matter the setup, using the thread_local keyword instead of the static keyword adds more overhead. I was, again, surprised by exactly how much assigning into it once and then reading it a single time once inside the function could have on the performance metrics, but it turns out that this is not free either.

It goes to show that having what the Closures WIP ISO C proposal asks for both C++-style Lambdas and C-style “Capture Functions” (nested functions that do not have the design, ABI issues, and Implementation Baggage of regular GNU Nested Functions)2 along with a Wide Function Pointer type would be better than trying to figure out a magic static or magic thread_local style of implementation.

We are not sure what to think of the Local Functions and Function Literals proposals3, because neither of them try to allow you to access local variables. Which is 90%4 of the reason anyone uses Nested Functions to begin with!

What Is Going On With GNU Nested Functions???

Honestly, I do NOT know at this point.

It’s worth saying that I almost had to cut out GNU Nested Functions because of how god-awfully the were performing in the GCC graphs. It made it exponentially harder to get a good, zoomed-in look at the rest of the entries. While some have talked about standardizing just GNU Nested Functions, I do not think that ISO C could standardize an extension like this in any kind of Good Faith and still call itself a language concerned about low-level code and speed. Its existing implementations are so performance-deleting it’s a wonder why the decades-old code generated for it hasn’t been improved or touched up. I can only hope that the forthcoming -ftrampoline-impl=heap code from GCC puts it more in-line with the “Normal Functions (Static)” or “Normal Functions (Thread Local)” category, but if the performance of the new trampoline is just as awful as the current one I’d consider GNU Nested Functions to be dead-on-arrival for a lot of use cases.

This sort of awful performance also retroactively justifies Clang’s public and open decision to never, ever implement GNU Nested Functions. On top of the security issues the typical stack-based trampoline creates, the performance qualities are so egregious that just asking everyone to use -fblocks and the Apple Blocks extension for this functionality is probably the lesser of two evils. It also brings into question whether a “lean” approach that grabs the “environment pointer” or the “stack frame” pointer directly, as in n36545 is a good idea to start with.

But, it’s premature to condemn n3654 because it’s unknown if the problem is the fact that the use of accessing variables through what is effectively __builtin_stack_address and a trampoline is why performance sucks so bad, or if it’s the way the trampoline screws with the stack. There are many compounding reasons why GNU Nested Functions as they exist today do so poorly, and more investigation is needed to make sure the approach in n3654 of accessing the “Context” of a nested function isn’t actually a huge performance footgun.

Final Takeways

Now that we have thoroughly evaluated the solution space for C, including many of the home-cooked favorite solutions written in plain C, I think the safe conclusions I can draw are:

- Lambdas (and the proposed Capture Functions2) are the best for performance, so long as perfect information is retained.

- A type-preserving closure (e.g. Lambdas or Capture Functions) combined with the smallest, thinnest possible type erasure (a Wide Function Pointer type) would bring immediate performance gains over existing C extensions and plain C code that does not modify the function signature.

- Both Apple Blocks and GNU Nested Functions have parts of their designs and implementations that are deeply problematic for integration into normal compilers.

- It is unclear if making what is effectively access to the function frame / “environment” through a pointer is an advisable course of action for the future of the C ecosystem.

- C users writing typical C code will, at some point, suffer some degree of performance loss in complex scenarios due to necessary type erasure to work with complex, compiler-generated closure types. Type-generic macro programming can help here, but the tradeoff for code size versus speed should be considered on whether to use a normal, type-erased interface versus an entirely (macro-)generic set of function calls.

Finally, both static and thread_local have performance cost, moreso on GCC than on Clang. I’d be interested to run the MSVC numbers too as more than just a quick “this works on the damn compiler” check, but I think these numbers are more than enough to draw general conclusions about the viability of the various approaches.

Happy New Year, and until next weird niche performance bit. 💚

- Banner and Title Photo by Lukas, from Pexels

P.S.

Methodology

The tests were ran on a 13-inch 2020 MacBook Pro M1. It has 16 GB of RAM and is on MacOS 15.7.2 Sequoia at the time the test was taken, using the stock MacOS AppleClang Compiler and the stock brew install gcc compiler in order to produce the numbers seen on December 28th, 2025.

The experimental setup used the Man or Boy test, but with the given k value loaded by calling a function in a DLL / Shared Object. The expected k value that the Man or Boy test is supposed to yield is also loaded from a DLL / Shared Object. This prevents optimizing out all recursion and doing enough ahead-of-time computation to simply collapse the benchmarked code into a constant-time, translation-time calculation. It ensures the benchmark is actually measuring the actual performance characteristics of the technique used, as all of them are computing from the same initial k value and all of them are expected to produce the same expected_k answer.

There 2 measures being conducted: Real (“wall clock”) Time and CPU Time. The time is gathered by running a single iteration of the code within a for loop. That loop runs anywhere from a couple thousand to hundreds of thousands of times to produce confidence in that run of the benchmark, and each loop run is considered an individual iteration. The iterations are then averaged to produce the first point after there is confidence that the measurement is accurate and the benchmark is warm. The iteration process to produce a single mean was then repeated 150 times. All 150 means are used as the points for the values (shown as transparent dots) on the bar graph, and the average of all of those 150 means is then used as the height of a bar in a bar graph.

The bars are presented side-by-side as a horizontal bar chart with various categories of C or C++ code being measured. The 13 total categories of C and C++ code are:

- no-op: Literally doing nothing. It’s just there to test environmental noise and make sure none of our benchmarks are so off-base that we’re measuring noise rather than computation. Helps keep us grounded in reality.

- Normal Functions: regular C functions which add an extra argument to the function call in order to pass more data. Somewhat similar in representation to rewriting qsort to qsort_r/qsort_s to pass a user data pointer.

- Normal Functions (Static): regular C function which uses a

staticvariable to pass the specific context to the next function. Not thread safe. - Normal Functions (Thread Local): same as “Normal Functions (Static)” but using a

thread_localvariable instead of astaticvariable. Obviously thread safe. - Lambdas (No Function Helpers): a solution using C++-style lambdas. Rather than using helper functions like

f0,f1, andf_1, we compute a raw lambda that stores the value meant to be returned for the Man-or-Boy test (with a body of just return i;) in the lambda itself and then pass that uniquely-typed lambda to the core of the test. The entire test is templated and uses a fake recursion template parameter to halt the translation-time recursion after a certain depth. - Lambdas: The same as above but actually using int f0(void), etc. helper functions at the start rather than lambdas. Tries to reduce optimizer pressure by using “normal” types which do not add to the generated number of lambda-typed, recursive, templated function calls.

- Lambdas (std::function_ref): The same as above, but rather than using a function template to handle each uniquely-typed lambda like a precious baby bird, it instead erases the lambda behind a

std::function_ref<int(void)>. This allows the recursive function to retain exactly one signature. - Lambdas (std::function): The same as above, but replaces

std::function_ref<int(void)>withstd::function<int(void)>. This is an allocating, C++03-style type. - Lambdas (Rosetta Code): The code straight out of the C++11 Rosetta Code Lambda section on the Man-or-Boy Rosetta Code implementation.

- Apple Blocks: Uses Apple Blocks to implement the test, along with the

__blockspecifier to refer directly to certain variables on the stack. - GNU Nested Functions (Rosetta Code): The code straight out of the C Rosetta Code section on the Man-or-Boy Rosetta Code implementation.

- GNU Nested Functions: GNU Nested Functions similar to the Rosetta Code implementation, but with some slight modifications in a hope to potentially alleviate some stack pressure if possible by using regular helper functions like

f0,f1, andf_1. - Custom C++ Class: A custom-written C++ class using a discriminated union to decide whether it’s doing a straight function call or attempting to engage in the Man-or-Boy recursion.

- C++03 shared_ptr (Rosetta Code): A C++ class using

std::enable_shared_from_thisandstd::shared_ptrwith a virtual function call to invoke the “right” function call during recursion.

Each bar graph has a black error bar at the end, representing the standard error of the measurements performed. At 150 iterations, the error bars (which are most easily understood and read in the linear graphs) are a decent visual approximation of whether or not two solutions are within a statistical threshold of one another.

The two compilers tested are Apple Clang 17 and GCC 15. There are two graph images for each kind of measurement (linear, logarithmic, and linear-but-with-outliers-removed) because one is for Apple Clang and the other is for GCC. This is particularly important because neither compiler implements the other’s closure extension (Clang does Apple Blocks but not Nested Functions, while GCC does Nested Functions in exclusively its C frontend but does not implement Apple Blocks).

MSVC was not tested because MSVC implements none of the extensions being tested, and we do not expect that its performance characteristics would be wildly different than what GCC or Clang are capable of. (In fact, we expect it might be a bit worse in all untested, non-scientific honesty.)

-

See: https://github.com/soasis/idk/tree/main/benchmarks/closures. ↩

-

See “Captures Functions: Rehydrated Nested Functions” from “Functions with Data - Closures in C”. ↩ ↩2

-

See “N3678 - Local functions” and “N3679 - Function literals”, https://www.open-std.org/JTC1/SC22/WG14/www/docs/n3678.pdf and https://www.open-std.org/JTC1/SC22/WG14/www/docs/n3679.pdf ↩

-

This is not a hard or scientific statistic. We simply catalogued a codebase that used GNU Nested Functions – of the thousands of uses, the overwhelming supermajority accessed variables contextually. A proposal that solves 10% of a codebases existing uses seems worthless. ↩

-

See “Access the Context of Nested Functions”, https://www.open-std.org/JTC1/SC22/WG14/www/docs/n3654.pdf. ↩