I had a vague idea that closures could have a variety of performance implications; I did not believe that so many of the chosen and potential designs for C and C++ extensions ones, however, were so… suboptimal.

But, before we get into how these things perform and what the cost of their designs are, we need to talk about what Closures are.

“Closures”?

Closures in this instance are programming language constructs that include data alongside instructions that are not directly related to their input (arguments) and their results (return values). They can be seen as a “generalization” of the concept of a function or function call, in that a function call is a “subset” of closures (e.g., the set of closures that do not include this extra, spicy data that comes from places outside of arguments and returns). These generalized functions and generalized function objects hold the ability to do things like work with “instance” data that is not passed to it directly (i.e., variables surrounding the closure off the stack) and, usually, some way to carry around more data than is implied by their associated function signature.

Pretty much all recent and modern languages include something for Closures unless they are deliberately developing for a target audience or for a source code design that is too “low level” for such a concept (such as Stack programming languages, Bytecode languages, or ones that fashion themselves as assembly-like or close to it). However, we’re going to be focusing on and looking specifically at Closures in C and C++, since this is going to be about trying to work with and – eventually – standardize something for ISO C that works for everyone.

First, let’s show a typical problem that arises in C code to show why closure solutions have popped up all over the C ecosystem, then talk about it in the context of the various solutions.

The Closure Problem

The closure problem can be neatly described by as “how do I get extra data to use within this qsort call?”. For example, consider setting this variable, in_reverse, as part of a bit of command line shenanigans, to change how a sort happens:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stddef.h>

static int in_reverse = 0;

int compare(const void* untyped_left, const void* untyped_right) {

const int* left = untyped_left;

const int* right = untyped_right;

return (in_reverse) ? *right - *left : *left - *right;

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

if (argc > 1) {

char* r_loc = strchr(argv[1], 'r');

if (r_loc != NULL) {

ptrdiff_t r_from_start = (r_loc - argv[1]);

if (r_from_start == 1 && argv[1][0] == '-' && strlen(r_loc) == 1) {

in_reverse = 1;

}

}

}

int list[] = { 2, 11, 32, 49, 57, 20, 110, 203 };

qsort(list, (sizeof(list)/sizeof(*list)), sizeof(*list), compare);

return list[0];

}

This uses a static variable to have it persist between both the compare function calls that qsort makes and the main call which (potentially) changes its value to be 1 instead of 0. Unfortunately, this isn’t always the best idea for more complex programs that don’t fit within a single snippet:

- it is impossible to have different “copies” of a

staticvariable, meaning all mutations done in all parts of the program that can seein_reverseare responsible for knowing the state before and after (e.g., heavily stateful programming of state that you may not own / cannot see); - working on

staticdata may produce thread contention/race conditions in more complex programs; - using

_Thread_localinstead ofstaticonly solves the race condition problem but does not solve the “shared across several places on the same thread” problem; - referring to specific pieces of data or local pieces of data (like

listitself) become impossible;

and so on, and so forth. This is the core of the problem here. It becomes more pronounced when you want to do things with function and data that are a bit more complex, such as Donald Knuth’s “Man-or-Boy” test code.

The solutions to these problems come in 4 major flavors in C and C++ code.

- Just reimplement the offending function to take a userdata pointer so you can pass whatever data you want (typical C solution, e.g. going from

qsortas the sorting function to BSD’sqsort_r1 or Annex K’sqsort_s2). - Use GNU Nested Functions to just Refer To What You Want Anyways.

- Use Apple Blocks to just Refer To What You Want Anyways.

- Use C++ Lambdas and some elbow grease to just Refer To What You Want Anyways.

Each solution has drawbacks and benefits insofar as usability and design, but as a quick overview we’ll show what it’s like using qsort (or qsort_r/qsort_s, where applicable). Apple Blocks, for starters, looks like this:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stddef.h>

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

// local, non-static variable

int in_reverse = 0;

// value changed in-line

if (argc > 1) {

char* r_loc = strchr(argv[1], 'r');

if (r_loc != NULL) {

ptrdiff_t r_from_start = (r_loc - argv[1]);

if (r_from_start == 1 && argv[1][0] == '-' && strlen(r_loc) == 1) {

in_reverse = 1;

}

}

}

int list[] = { 2, 11, 32, 49, 57, 20, 110, 203 };

qsort_b(list, (sizeof(list)/sizeof(*list)), sizeof(*list),

// Apple Blocks are Block Expressions, meaning they do not have to be stored

// in a variable first

^(const void* untyped_left, const void* untyped_right) {

const int* left = untyped_left;

const int* right = untyped_right;

return (in_reverse) ? *right - *left : *left - *right;

}

);

return list[0];

}

and GNU Nested Functions look like this:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stddef.h>

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

// local, non-static variable

int in_reverse = 0;

// modify variable in-line

if (argc > 1) {

char* r_loc = strchr(argv[1], 'r');

if (r_loc != NULL) {

ptrdiff_t r_from_start = (r_loc - argv[1]);

if (r_from_start == 1 && argv[1][0] == '-' && strlen(r_loc) == 1) {

in_reverse = 1;

}

}

}

int list[] = { 2, 11, 32, 49, 57, 20, 110, 203 };

// GNU Nested Function definition, can reference `in_reverse` directly

// is a declaration/definition, and cannot be used directly inside of `qsort`

int compare(const void* untyped_left, const void* untyped_right) {

const int* left = untyped_left;

const int* right = untyped_right;

return (in_reverse) ? *right - *left : *left - *right;

}

// use in the sort function without the need for a `void*` parameter

qsort(list, (sizeof(list)/sizeof(*list)), sizeof(*list), compare);

return list[0];

}

or, finally, C++-style Lambdas:

#define __STDC_WANT_LIB_EXT1__ 1

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stddef.h>

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

int in_reverse = 0;

if (argc > 1) {

char* r_loc = strchr(argv[1], 'r');

if (r_loc != NULL) {

ptrdiff_t r_from_start = (r_loc - argv[1]);

if (r_from_start == 1 && argv[1][0] == '-' && strlen(r_loc) == 1) {

in_reverse = 1;

}

}

}

// lambdas are expressions, but we can assign their unique variable types with `auto`

auto compare = [&](const void* untyped_left, const void* untyped_right) {

const int* left = (const int*)untyped_left;

const int* right = (const int*)untyped_right;

return (in_reverse) ? *right - *left : *left - *right;

};

int list[] = { 2, 11, 32, 49, 57, 20, 110, 203 };

// C++ Lambdas don't automatically make a trampoline, so we need to provide

// one ourselves for the `qsort_s/r` case so we can call the lambda

auto compare_trampoline = [](const void* left, const void* right, void* user) {

typeof(compare)* p_compare = user;

return (*p_compare)(left, right);

};

qsort_s(list, (sizeof(list)/sizeof(*list)), sizeof(*list), compare_trampoline, &compare);

return list[0];

}

To solve this gaggle of problems, pretty much every semi-modern language (that isn’t assembly-adjacent or based on some kind of state/stack programming) provide some idea of being able to associate some set of data with one or more function calls. And, particularly for Closures, this is done in a local way without passing it as an explicit argument. As it turns out, all of those design choices – including the ones in C – have pretty significant consequences on not just usability, but performance.

Not A Big Overview

This article is NOT going to talk in-depth about the design of all of the alternatives or other languages. We’re focused on the actual cost of the extensions and what they mean. A detailed overview of the design tradeoffs, their security implications, and other problems, can be read at the ISO C Proposal for Functions with Closures here; it also gets into things like Security Implications, ABI, current implementation impact, and more of the various designs. The discussion in the paper is pretty long and talks about the dozens of aspects of each solution down to both the design aspect and the implementation quirks. We encourage you to dive into that proposal and read it to figure out if there’s something more specific you care about insofar as some specific design portion. But, this article is going to be concerned about one thing and one thing only:

Purrrrrrrformance :3!

In order to measure this cost, we are going to take Knuth’s Man-or-Boy test and benchmark various styles of implementation in C and C++ using various different extensions / features for the Closure problem. The Man-or-Boy test is an efficient measure of how well your programming language can handle referring to specific entities while engaging in a large degree of recursion and self-reference. It can stress test various portions of how your program creates and passes around data associated with a function call, and if your programming language design is so goofy that it can’t refer to a specific instance of a variable or function argument, it will end up producing the wrong answer and breaking horrifically.

Anatomy of a Benchmark: Raw C

Here is the core of the Man-or-Boy test, as implemented in raw C. This implementation3 and all the others are available online for us all to scrutinize and yell at me for messing up, to make sure I’m not slandering your favorite solution for Closures in this space.

// ...

static int eval(ARG* a) {

return a->fn(a);

}

static int B(ARG* a) {

int k = *a->k -= 1;

ARG args = { B, &k, a, a->x1, a->x2, a->x3, a->x4 };

return A(&args);

}

static int A(ARG* a) {

return *a->k <= 0 ? eval(a->x4) + eval(a->x5) : B(a);

}

// ...

You will notice that there is a big, fat, ugly ARG* parameter hanging around all of these functions. That is because, as stated before, plain ISO C cannot handle passing the data around unless it’s part of a function’s arguments. Because the actual core of the Man-or-Boy experiment is the ability to refer to specific values of k that exist during the recursive run of the program, we need to actually modify the function signature and thereby cheat some of the implicit Man-or-Boy requirements of not passing the value in directly. Here’s what ARG looks like:

typedef struct arg {

int (*fn)(struct arg*);

int* k;

struct arg *x1, *x2, *x3, *x4, *x5;

} ARG;

static int f_1(ARG* _) {

return -1;

}

static int f0(ARG* _) {

return 0;

}

static int f1(ARG* _) {

return 1;

}

static int eval(ARG* a) {

// ...

}

// ...

And this is how it gets used in the main body of the function in order to compute the right answer and benchmark it:

static void normal_functions_rosetta(benchmark::State& state) {

const int initial_k = k_value();

const int expected_k = expected_k_value();

int64_t result = 0;

for (auto _ : state) {

int k = initial_k;

ARG arg1 = { f1, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL };

ARG arg2 = { f_1, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL };

ARG arg3 = { f_1, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL };

ARG arg4 = { f1, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL };

ARG arg5 = { f0, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL };

ARG args = { B, &k, &arg1, &arg2, &arg3, &arg4, &arg5 };

int value = A(&args);

result += value == expected_k ? 1 : 0;

}

if (result != state.iterations()) {

state.SkipWithError("failed: did not produce the right answer!");

}

}

BENCHMARK(normal_functions_rosetta);

Everything within the for (auto _ : state) { ... } is benchmarked. For those paying attention to the code and find it looking familiar, it’s because that code is the basic structure all Google Benchmark4 code finds itself looking like. I’ve wanted to swap to Catch25 for a long time now to change to their benchmarking infrastructure, but I’ve been stuck on Google Benchmark because I’ve made a lot of graph-making tools based on its JSON output and I have not vetted Catch2’s JSON output yet to see if it has all of the necessary bits ‘n’ bobbles I use to de-dedup runs and compute statistics.

Everything outside is setup (the part above the for loop) or teardown/test correction (the part below the for loop). The initialization of the ARG argss cannot be moved outside of the measuring loop because each invocation of A – the core of the Man-or-Boy experiment – modifies the k of the ARG parameter, so all of them have to be inside. Conceivably, arg1 .. 5 could be moved out of the loop, but I am very tired of looking at the eight or nine variations of this code so someone else can move it and tell me if Clang or GCC has lots of compiler optimization sauce and doesn’t understand that those 5 argIs can be hoisted out of the loop.

The value k is 10, and expected_k is -67. The expected, returned k value is dependent on the input k value, which controls how deep the Man-or-Boy test would recurse on itself to produce its answer. Therefore, to prevent GCC and Clang and other MEGA POWERFUL PILLAR COMPILERS from optimizing the entire thing out and just replacing the benchmark loop with ret -67, both k_value() and expected_k_value() come from a Dynamic Link Library (.dylib on MacOS, .so on *nix platforms, .dll on Windows platforms) to make sure that NO amount of optimization (Link Time Optimization/Link Time Code Generation, Inlining Optimization, Cross-Translation Unit Optimization, and Automatic Constant Expression Optimization) from C or C++ compilers could fully preempt all forms of computation.

This allows us to know, for sure, that we’re actually measuring something and not just testing how fast a compiler can load a number into a register and test it against state.iterations(). And, since we know for sure, we can now talk the general methodology.

Methodology

The tests were ran on a dying 13-inch 2020 MacBook Pro M1 that has suffered several toddler spills and two severe falls. It has 16 GB of RAM and is on MacOS 15.7.2 Sequoia at the time the test was taken, using the stock MacOS AppleClang Compiler and the stock brew install gcc compiler in order to produce the numbers seen on December 6th, 2025.

There 2 measures being conducted: Real Time and CPU Time. The time is gathered by running a single iteration of the code within the for loop anywhere from a couple thousand to hundreds of thousands of times to produce confidence in that run of the benchmark. This is then averaged to produce the first point. The process is repeated 50 times, repeating that many iterations to build further confidence in the measurement. All 50 means are used as the points for the values, and the average of all of those 50 means is then used as the height of a bar in a bar graph.

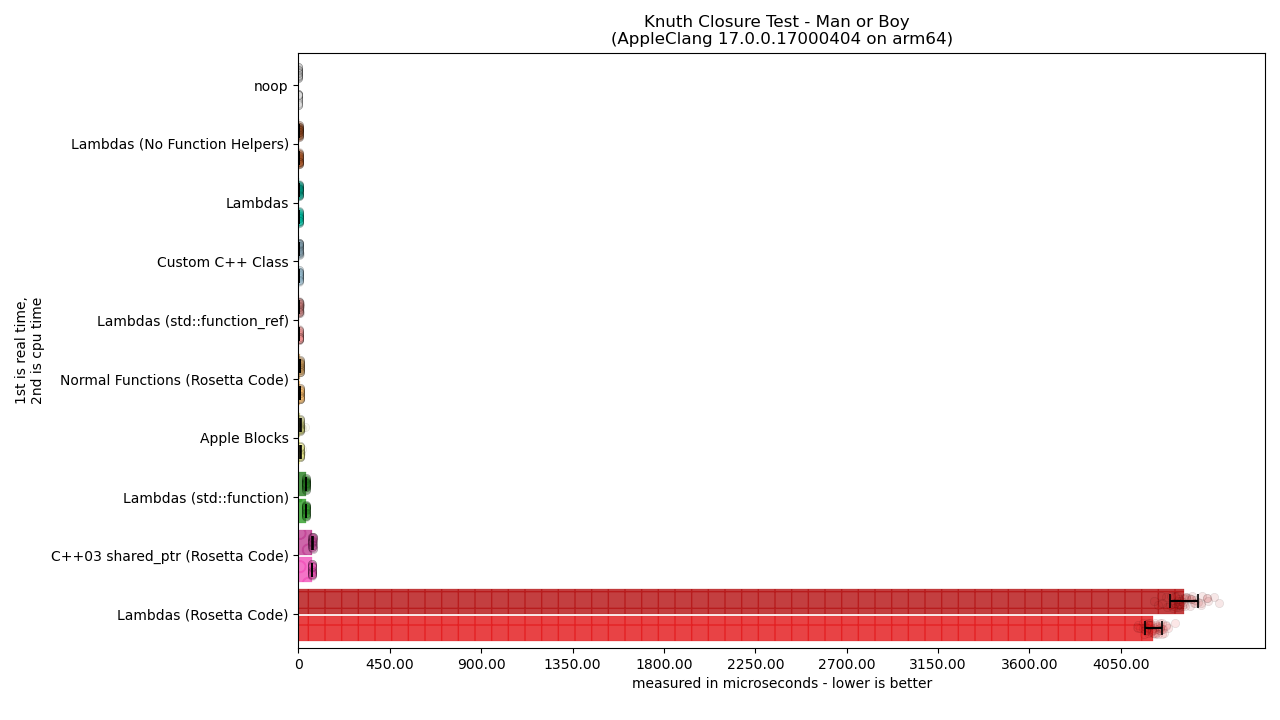

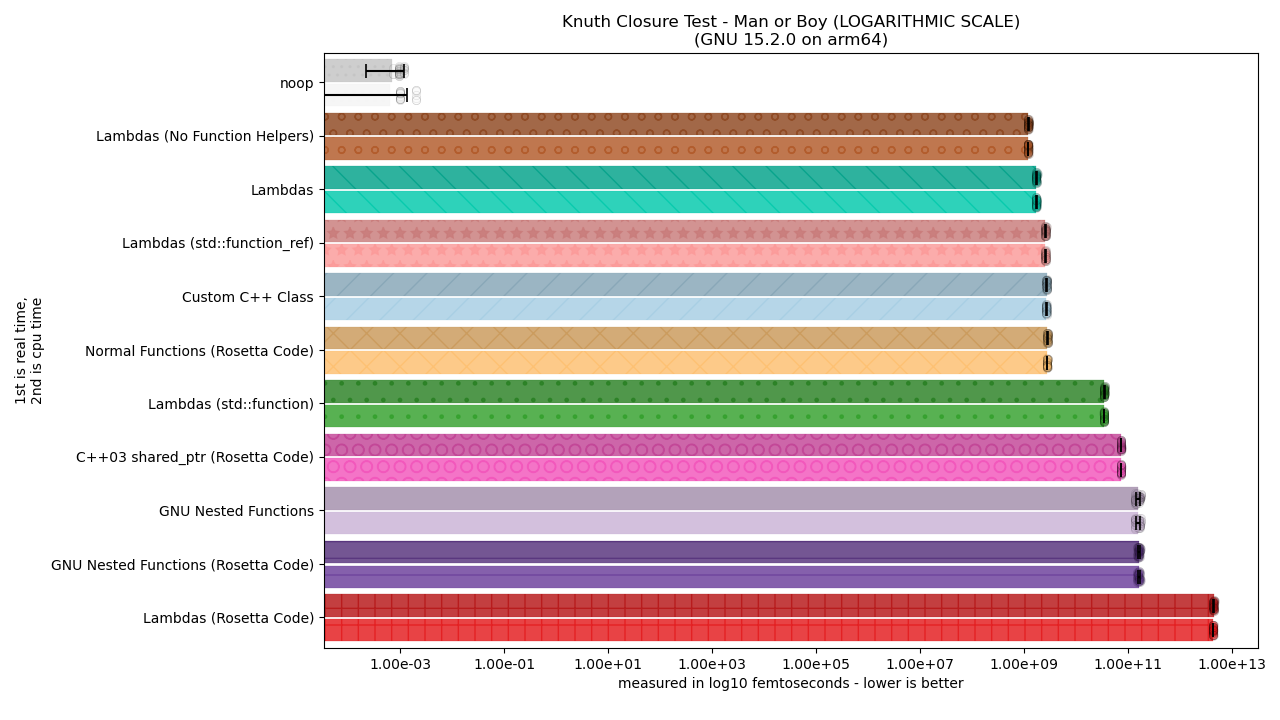

The bars are presented side-by-side as a horizontal bar chart with 11 categories of C or C++ code being measured. The 11 categories are:

no-op: Literally doing nothing. It’s just there to test environmental noise and make sure none of our benchmarks are so off-base that we’re measuring noise rather than computation. Helps keep us grounded in reality.Lambdas (No Function Helpers): a solution using C++-style lambdas. Rather than using helper functions likef0,f1, andf_1, we compute a raw lambda that stores the value meant to be returned for the Man-or-Boy test (return i;) in the lambda itself and then pass that uniquely-typed lambda to the core of the test. The entire test is templated and uses a fakerecursiontemplate parameter to halt the recursion after a certain depth.Lambdas: The same as above but actually usingint f0(void), etc. helper functions at the start rather than lambdas. Reduces inliner pressure by using “normal” types which do not add to the generated number of lambda-typed, recursive, templated function calls.Lambdas (std::function_ref): The same as above, but rather than using a function template to handle each uniquely-typed lambda like a precious baby bird, it instead erases the lambda behind astd::function_ref<int(void)>. This allows the recursive function to retain exactly one signature.Lambdas (std::function): The same as above, but replacesstd::function_ref<int(void)>withstd::function<int(void)>. This is its allocating, C++03-style type.Lambdas (Rosetta Code): The code straight out of the C++11 Rosetta Code Lambda section on the Man-or-Boy Rosetta Code implementation.Apple Blocks: Uses Apple Blocks to implement the test, along with the__blockspecifier to refer directly to certain variables on the stack.GNU Nested Functions (Rosetta Code): The code straight out of the C Rosetta Code section on the Man-or-Boy Rosetta Code implementation.GNU Nested Functions: GNU Nested Functions similar to the Rosetta Code implementation, but with some slight modifications in a hope to potentially alleviate some stack pressure if possible by using regular helper functions likef0,f1, andf_1.Custom C++ Class: A custom-written C++ class using a discriminated union to decide whether it’s doing a straight function call or attempting to engage in the Man-or-Boy recursion.C++03 shared_ptr (Rosetta Code): A C++ class usingstd::enable_shared_from_thisandstd::shared_ptrwith a virtual function call to invoke the “right” function call during recursion.

The two compilers tested are Apple Clang 17 and GCC 15. There are two graph images because one is for Apple Clang and the other is for GCC. This is particularly important because neither compiler implements the other’s closure extension (Clang does Apple Blocks but not Nested Functions, while GCC does Nested Functions in exclusively its C frontend but does not implement Apple Blocks6).

The Results

Ta-da!

For the vision-impaired, a text description is available.

For the vision-impaired, a text description is available.

… Oh. That looks awful.

It turns out that some solutions are so dogwater that it completely screws up our viewing graphs. But, it does let us know that Lambdas using the Rosetta Code style are so unbelievably awful that it is several orders of magnitude more expensive than any other solution presented! One has to wonder what the hell is going on in the code snippet there, but first we need to make the graphs more legible. To do this we’re going to be using the (slightly deceptive) LOGARITHMIC SCALING. This is a bit deadly to do because it tends to mislead people about how much of a change there is, so please pay attention to the potential order of magnitude gains and losses when going from one bar graph to another.

For the vision-impaired, a text description is available.

For the vision-impaired, a text description is available.

For the vision-impaired, a text description is available.

There we go. Now we can talk about the various solutions and – in particular – why “lambdas” have 4 different entries with such wildly differing performance profiles. First up, let’s talk about the clear performance winners.

Lambdas: On Top!

Not surprising to anyone who has been checked in to C++, lambdas that are used directly and not type-erased are on top. This means there’s a one-to-one mapping between a function call and a given bit of execution. We are cheating by using a constant parameter to stop the uniquely-typed lambdas being passed into the functions from recursing infinitely, which makes the Man-or-Boy function look like this:

template <int recursion = 0>

static int a(int k, const auto& x1, const auto& x2, const auto& x3, const auto& x4, const auto& x5) {

if constexpr (recursion == 11) {

::std::cerr << "This should never happen and this code should never have been generated." << std::endl;

::std::terminate();

return 0;

}

else {

auto B = [&](this const auto& self) { return a<recursion + 1>(--k, self, x1, x2, x3, x4); };

return k <= 0 ? x4() + x5() : B();

}

}

Every B is its own unique type and we are not erasing that unique type when using the expression as an initializer to B. This means that when we call a again with B (the self in this lambda here using Deduced This, a C++23 feature that cannot be part of the C version of lambdas) which means we need to use auto parameters (a shortcut way of writing template parameters) to take it. But, since every parameter is unique, and every B is unique, calling this recursively means that, eventually, C++ compilers will actually just completely crash out/toss out-of-memory errors/say we’ve compile-time recursed too hard, or similar. That’s why the compile-time if constexpr on the extra, templated recursion parameter needs to have some arbitrary limit. Because we know k starts at 10 for this test, we just have some bogus limit of “11”.

This results in a very spammy recursive chain of function calls, where the actual generated names of these template functions are far more complex than a and can run the compiler into the ground / cause quite a bit of instantiations if you let recursion get to a high enough value. But, once you add the limit, the compiler gets perfect information about this recursive call all the way to every leaf, and thus is able to not only optimize the hell out of it, but refuse to generate the other frivolous code it knows won’t be useful.

Lambdas are also Fast, even when Type-Erased

You can observe a slight bump up in performance penalty when a Lambda is erased by a std::function_ref. This is a low-level, non-allocating, non-owning, slim “view” type that is analogous to what a language-based wide function pointer type would be in C. From this, it allows us to guess how good Lambdas in C would be even if you had to hide them behind a non-unique type.

The performance metrics are about equivalent to if you hand-wrote a C++ class with a custom operator() that uses a discriminated union, no matter which compiler gets used to do it. It’s obviously not as fast as having access to a direct function call and being able to slurp-inline optimize, but the performance difference is acceptable when you do not want to engage in a large degree of what is called “monomorphisation” of a generic routine or type. And, indeed, outside of macros, C has no way of doing this innately that isn’t runtime-based.

A very strong contender for a good solution!

Lambdas: On…. Bottom, too?

One must wonder, then, why the std::function Lambdas and the Rosetta Code Lambdas are either bottom-middle-of-the-road or absolutely-teary-eyed-awful.

Starting off, the std::function Lambdas are bad because of exactly that: std::function. std::function is not a “cheap” closure; it is a potentially-allocating, meaty, owning function abstraction. This means that it’s safe to make one and pass it around and store it and call it later; the cost of this is, obviously, that you’re allocating (when the type is big enough) for that internal storage. Part of this is alleviated by using const std::function<int(void)>& parameters, taking things by reference and only generating a new object when necessary. This prevents copying on every function call. Both the Rosetta Lambdas and regular std::function Lambdas code do the by-reference parameters bit, though, so where does the difference come in? It actually has to do with the Captures. Here’s how std::function Lambdas defines the recursive, self-referential lambda and uses it:

using f_t = std::function<int(void)>;

inline static int A(int k, const f_t& x1, const f_t& x2, const f_t& x3, const f_t& x4, const f_t& x5) {

f_t B = [&] { return A(--k, B, x1, x2, x3, x4); };

return k <= 0 ? x4() + x5() : B();

}

And, here is how the Rosetta Code Lambdas defines the recursive, self-referential lambda and uses it:

using f_t = std::function<int(void)>;

inline static int A(int k, const f_t& x1, const f_t& x2, const f_t& x3, const f_t& x4, const f_t& x5) {

f_t B = [=, &k, &B] { return A(--k, B, x1, x2, x3, x4); };

return k <= 0 ? x4() + x5() : B();

}

The big problem here is in the use of the =. What = by itself in the front of a lambda capture clause means is “copy all the visible variables in and hold onto that copy” (unless the capture for that following variable is “overridden” by a &var, address capture). Meanwhile, the & is the opposite: it means “refer to all the visible variables directly by their address and do not copy them in”. So, while the std::function Lambda is (smartly) referring to stuff directly without copying because we know for the Man-or-Boy test that referring to things directly is not an unsafe operation, the general = causes that for the several dozen recursive iterations through the function, it is copying all five allocating std::function arguments. So the first call creates a B that copies everything in, and then passes that in, and then the next call copies the previous B and the 4 normal functions, and then passes that in to the next B, and then it copies both previous B’s, and this stacks for the depth of the callgraph (some 10 times since k = 10 to start).

You can imagine how much that completely screws with the performance, and it explains why the Rosetta Code Lambdas code behaves so poorly in terms of performance. But, this also raises a question: if referring to everything by-reference saves so much speed, then why does GNU Nested Functions – in all its variants – perform so poorly? After all, Nested Functions capture everything by reference / by address, exactly like a lambda does with [&].

Similarly, if allocating over and over again was so expensive, how come Apple Blocks and C++03 shared_ptr Rosetta Code-style versions of the Man-or-Boy test don’t perform nearly as badly as the Rosetta Code Lambdas? Are we not copying the value of the arguments into a newly created Apple Block and, thusly, tanking the performance metrics? Well, as it turns out, there’s many reasons for these things, so let’s start with GNU Nested Functions.

Nested Functions and The Stack

I’ve written about it dozens of times now, but the prevailing and most common implementation of Nested Functions is with an executable stack. The are a lot of security and other implications for this, but all you need to understand is that the reason GCC did this is because it was an at-the-time slick encoding of both the location of the variables and the routine itself. Allocating a chunk of data off of the current programming stack means that the “environment context”/”this closure” pointer has the same anchoring address as the routine itself. This means you can encode both the location of the data to know what to access and the address of a function’s entry point into a single thing that works with your typical setup-and-call convention that comes with invoking a standard ISO C function pointer.

But think about that, briefly, in terms of optimization.

You are using the function’s stack frame at that precise point in the program as the “base address” for this executable code. That base address also means that all the variables associated with it need to be reachable from that base address: i.e., that things are not stuffed in registers, but that you are referring to the same variables as modified by the enclosing function around your nested function. Principally, this means that your function needs to have all of the following now so that GNU Nested Functions actually work.

- A stack that is executable so that the base address used for the trampoline can be run succinctly.

- A real function frame that exists somewhere in memory to serve as the base address for the trampoline.

- Real objects in memory backing the names of the captured variables to be accessed.

This all seems like regular consequences, until you tack on the second order effects from the point of optimization.

- A stack that now has both data and instructions all blended into itself.

- A real function frame, which means no omission of a frame pointer and no collapsing / inlining of that function frame.

- Real objects that all have their address taken that are tied to the function frame, which must be memory-accessible and which the compiler now has a hard time telling if they can simply be exchanged through registers or if they need to actually sit somewhere in memory.

In other words: GNU Nested Functions have created the perfect little storm for what might be the best optimizer-murderer. The reason it performs so drastically poorly (worse than even allocating lambdas inside of a std::function or C++03-style virtual function calls inside of a bulky, nasty C++ std::shared_ptr) by a whole order of magnitude or more is that everything about Nested Functions and their current implementation is basically Optimizer Death. If the compiler can’t see through everything – and the Man-or-Boy test with a non-constant value of k and expected_k – GNU Nested Functions deteriorate rapidly. It takes every core optimization technique that we’ve researched and maximized on in the last 30 years and puts a shotgun to the side of its head once it can’t pre-compute k and expected_k.

The good news is that GCC has completed a new backing implementation for GNU Nested Functions, which uses a heap-based trampoline. Such a trampoline does not interfere with the stack, would allow for omission of frame pointers while referring directly to the data itself (which may prevent the wrecking of specific kinds of inlining optimizations), and does not need an executable stack (just a piece of memory from ✨somewhere✨ it can mark executable). This may have performance closer to Apple Blocks, but we don’t have a build of the latest GCC to test it with. But, when we do, we can simply add the compilation flag -ftrampoline-impl=heap to the two source files in CMake and then let the benchmarks run again to see how it stacks up!

Finally, there is a minor performance degradation because our benchmarking software is in C++ and this extension exists exclusively in the C frontend of GCC. That means I have to use an extern function call within the benchmark loop to get to the actual code. Within the function call, however, all of this stuff should be optimized down, so the cost of a single function call’s stack frame shouldn’t be so awful, but I expect to try to dig into this better to help make sure the extern of a C function call isn’t making things dramatically worse than they are. Given it’s a different translation unit and it’s not being compiled as a separate static or dynamic library, it should still link together and optimize cleanly, but given how bad it’s performing? Every possible issue is on the table.

What about Apple Blocks?

Apple Blocks are not the fastest, but they are the best of the C extensions while being the worst of the “fast” solutions. They are not faster than just hacking the ARG* into the function signature and using regular normal C function calls, unfortunately, and that’s likely due to their shared, heap-ish nature. The saddest part about Apple Blocks is that it works using a Blocks Runtime that is already as optimized as it can possibly be: Clang and Apple both document that while the Blocks Runtime does manage an Automatic Reference Counted (ARC) Heap of Block pointers, when a Block is first created it will literally have its memory stored on the stack rather than in the heap. In order to move it to the heap, one must call Block_copy to trigger the “normal” heap-based shenanigans. We never call Block_copy, so this is with as-fast-as-possible variable access and management with few allocations.

It’s very slightly disappointing that: normal C functions with an ARG* blob; a custom C++ class using a discriminated union and operator(); any mildly conscientious use of lambdas; and, any other such shenanigans perform better than the very best Apple Blocks has to offer. One has to imagine that all of the ARC management functions made to copy the int^(void) “hat-style” function pointers, even if they end up not doing much for the data stored on the stack, impacted the results here. But, this is also somewhat good news: because Apple Block hat pointers are cheaply-copiable entities (they are just pointers to a Block object), it means that even if we copy all of the arguments into the closure every function call, that copying is about as cheap as it can get. Obviously, as regular “Lambdas” and “Lambdas (No Function Helpers)” demonstrate, being able to just slurp everything up by address/by reference – including visible function arguments – with [&] saves us a teensy, tiny bit of time7.

The cheapness of int^(void) hat-pointer function types is likely the biggest saving grace for Apple Blocks in this benchmark. In the one place we need to be careful, we rename the input argument k to arg_k and then make a __block variable to actually refer to a shared int k (and get the right answer):

static int a(int arg_k, fn_t ^ x1, fn_t ^ x2, fn_t ^ x3, fn_t ^ x4, fn_t ^ x5) {

__block int k = arg_k;

__block fn_t ^ b = ^(void) { return a(--k, b, x1, x2, x3, x4); };

return k <= 0 ? x4() + x5() : b();

}

All of the x1, x2, and x3 – like the bad Lambda case – are copied over and over and over again. One could change the name of all the arguments arg_xI and then have an xI variable inside that is marked __block, but that’s more effort and very unlikely to have any serious impact on the code while possibly degrading performance for the setup of multiple shared variables that all have to also be ARC-reference-counted and be stored inside each and every new b block that is created.

A Brief Aside: Self-Referencing Functions/Closures

It’s also important to note that just writing this:

static int a(int arg_k, fn_t ^ x1, fn_t ^ x2, fn_t ^ x3, fn_t ^ x4, fn_t ^ x5) {

__block int k = arg_k;

fn_t ^ b = ^(void) { return a(--k, b, x1, x2, x3, x4); };

return k <= 0 ? x4() + x5() : b();

}

(no __block on the b variable) is actually a huge bug. Apple Blocks, like older C++ Lambdas, cannot technically refer to “itself” inside. You have to refer to the “self” by capturing the variable it is assigned to. For those who use C++ and are familiar with the lambdas over there, it’s like making sure you capture the variable you initialize with the lambda by reference while also making sure it has a concrete type. It can only be escaped by using auto and Deducing This, or some other combination of referential-use. That is:

auto x = [&x](int v) { if (v != limit) x(v + 1); return v + 8; }does not compile, as the typeautoisn’t figured out yet;std::function_ref<int(int)> x = [&x](int v) { if (v != limit) x(v + 1); return v + 8; }compiles but due to C++ shenanigans produces a dangling reference to a temporary lambda that dies after the full expression (the initialization);std::function<int(int)> x = [&x](int v) { if (v != limit) x(v + 1); return v + 8; }compiles and works with no segfaults becausestd::functionallocates, and the reference to itself&xis just fine.- and, finally,

auto x = [](this const auto& self, int v) { if (v != limit) self(v + 1); return v + 8; }which compiles and works with no segfaults because the invisibleselfparameter is just a reference to the current object.

The problem with the most recent Apple Blocks snippet just above is that it’s the equivalent of doing

std::function<int(int)> x = [x](int v) { if (v != limit) x(v + 1); return v + 8; }

Notice that there’s no &x in the lambda initializer’s capture list. It’s copying an (uninitialized) variable by-value into the lambda. This is what Apple Blocks set into a variable that does not have a __block specifier, like in our bad code case with b.

All variations of this on all implementations which allow for self-referencing allow this and compile some form of this. You would imagine some implementations would warn about this, but this is leftover nonsense from allowing a variable to refer to itself in its initialization. The obvious reason this happens in C and C++ is because you can create self-referential structures, but unfortunately neither language provided a safe way to do this generally. C++23’s Deducing This does not work inside of regular functions and non-objects, so good luck applying it to other places and other extensions8. The only extension which does not suffer this problem is GNU Nested Functions, because it creates a function declaration / definition rather than a variable with an initializer. Thus, this code from the benchmarks works:

inline static int gnu_nested_functions_a(int k, int xl(void), int x2(void), int x3(void), int x4(void), int x5(void)) {

int b(void) {

return gnu_nested_functions_a(--k, b, xl, x2, x3, x4);

}

return k <= 0 ? x4() + x5() : b();

}

And it has the semantics one would expect, unlike how Blocks, Lambdas, or others with default by-value copying work.

In the general case, this is what the paper __self_func was going to solve9, but… that’s going to need some time for me to convince WG14 that maybe it IS actually a good idea. We can probably just keep writing the buggy code a few dozen more times for the recursion case and keep leaving it error prone, but I’ll try my best to convince them one more time that the above situation is very not-okay.

Thinking It Over

While the Man-or-Boy test isn’t exactly the end-all, be-all performance test, due to flexing both (self)-referential data and utilization of local copies with recursion, it is surprisingly suitable for figuring out if a closure design is decent enough in a mid to high-level programming language. It also gives me some confidence that, at the very least, the baseline for performance of statically-known, compile-time understood, non type-erased, callable Closure objects will have the best implementation quality and performance tradeoffs for a language like ISO C no matter the compiler implementation.

In the future, at some point, I’ll have to write about why that is. It’s a bit upside down from the perspective of readers of this blog to first address performance and then later write about the design, but it’s nice to make sure we’re not designing ourselves into a bad performance corner at the outset of this whole adventure.

Learned Insights

Surprising nobody, the more information the compiler is allowed to accrue (the Lambda design), the better its ability to make the code fast. What might be slightly more surprising is that a slim, compact layer of type erasure – not a bulky set of Virtual Function Calls (C++03 shared_ptr Rosetta Code design) – does not actually cost much at all (Lambdas with std::function_ref). This points out something else that’s part of the ISO C proposal for Closures (but not formally in its wording): Wide Function Pointers.

The ability to make a thin { some_function_type* func; void* context; } type backed by the compiler in C would be extremely powerful. Martin Uecker has a proposal that has received interest and passing approval in the Committee, but it would be nice to move it along in a nice direction. My suggestion is having % as a modifier, so it can be used easily since wide function pointers are an extremely prevalent concept. Being able to write something like the following would be very easy and helpful.

typedef int(compute_fn_t)(int);

int do_computation(int num, compute_fn_t% success_modification);

A wide function pointer type like this would also be traditionally convertible from a number of already existing extensions, too, where GNU Nested Functions, Apple Blocks, C++-style Lambdas, and more could create the appropriate wide function pointer type to be cheaply used. Additionally, it also works for FFI: things like Go closures already use GCC’s __builtin_call_with_static_chain to transport through their Go functions in C. Many other functions from other languages could be cheaply and efficiently bridged with this, without having to come up with harebrained schemes about where to put a void* userdata or some kind of implicit context pointer / implicit environment pointer.

Existing Extensions?

Unfortunately – except for the Borland closure annotation – there’s too many things that are performance-stinky about existing C extensions to this problem. It’s no wonder GCC is trying to add -ftrampoline-impl=heap to the story of GNU Nested Functions; they might be able to tighten up that performance and make it more competitive with Apple Blocks. But, unfortunately, since it is heap-based, there’s a real chance that its maximum performance ceiling is only as good as Apple Blocks, and not as good as a C++-style Lambda.

Both GNU Nested Functions and Apple Blocks – as they are implemented – do not really work well in ISO C. GNU Nested Functions because their base design and most prevalent implementation are performance-awful, but also Apple Blocks because of the copying and indirection runtime of Blocks that manage ARC pointers providing a hard upper limit on how good the performance can actually be in complex cases.

Regular C code, again, performs middle-of-the-road here. It’s not the worst of it, but it’s not the best at all, which means there’s some room beneath how we could go having the C code run. While it’s hard to fully trust the Rosetta Code Man-or-Boy code for C as the best, it is a pretty clear example of how a “normal” C developer would do it and how it’s not actually able to hit maximum performance for this situation.

I wanted to add a version of regular C code that used a dynamic array with statics to transfer data, or a bunch of thread_locals, but I could not bring myself to actually care enough to write a complex association scheme from a specific invocation of the recursive function a and the slot of dynamic data that represented the closure’s data. I’m sure there’s schemes for it and I could think of a few, but at that point it’s such a violent contortion to get a solution going that I figured it simply wasn’t worth the effort. But, as always,

pull requests are welcome. 💚

- Banner and Title Photo by Lukas, from Pexels

-

See: https://github.com/soasis/idk/tree/main/benchmarks/closures. ↩

-

See https://github.com/catchorg/Catch2/blob/devel/docs/benchmarks.md. And try it out. It’s pretty good, I just haven’t gotten off my butt to make the swap to it yet. ↩

-

Apple Blocks used to have an implementation in GCC that could be turned on and it used a Blocks Runtime to achieve it. But, I think it was gutted when some NeXT support and Objective-C stuff was wiped out after being unmaintained for some time. There’s been talk of reintroducing it, but obviously someone has to actually sit down and either redo it from scratch (advantageous because Apple has changed the ABI of Blocks) or try to resurrect / fix the old support for this stuff. ↩

-

Apple Blocks cannot have the “by address” capturing mechanism it has – the

__blockstorage class modifier – applied to function arguments, for some reason. So, all function arguments are de-facto copied into a Block Expression unless someone saves a temporary inside the body of the function before the Block and then uses__blockon that to make it a by-reference capture. ↩ -

It also works on a template basis in order to deduce

this– theconst auto&is a templated parameter and is usually used to do things like allow a member function to be bothconstand non-constwhere possible when generated. ↩ -

WG14 rejected the paper last meeting, unfortunately, as not motivated enough. Funnily enough, it was immediately after this meeting that I got slammed in the face with this bug. Foresight and “being prepared” is just not something even the most diehard C enthusiasts really embodies, unfortunately, and most industry vendors tend to take a more strongly conservative position over a bigger one. ↩