… Let’s talk about something that has haunted me for over a year now.

Seeing discussion after discussion, paper after paper, point after point being made about references inside nullable types like variant<T&, monostate>, optional<T&>, expected<T&> and its friends, I am now beyond compelled to speak. The straws that finally tipped me from my year+ hiatus on this subject were a paper by Professor Peter Sommerlad in the latest C++ mailing, asking for a simplified optional<T&> (and object_ptr) in the interest of safety for MISRA C++-type folk, as well as another paper by James Berrow, who pursued his objections to the 2D Graphics Proposal with a thorough scholarship that demanded both respect and attention.

optional<T&> (and object_ptr) are minefields. Since MISRA’s paper cites my old paper – p1175 – it seems I can no longer blissfully turn a blind eye and pretend what went down at the November 2018 San Diego meeting just didn’t happen. During that meeting, I explicitly told the room that I would not bring another paper forward to help resolve this issue. I will not be… but I did promise that I would fully vet the design space.

That vetting is done in a yet-unpublished C++ paper d1683, a secret paper I have been never quite been able to force myself to finish writing. I could not write it because I feel I grossly misled myself and walked into a trap. In fact, I still do feel that way. It makes me feel sick that I am even picking up my pen to once more write about this utter travesty of a topic, most certainly not for the reasons you may expect. In an effort to do a good job and not sabotage Professor Sommerlad’s generally excellent work and consideration, I have bottled (nearly) all of the purely technical observations into d1683.

The rest of this reading is for those of you who can stomach messy, non-technical humanity that birthed the fullness of the viscerally methodical and mechanical understanding I leave for you in the paper. You may stop here if you wish,

though I certainly wish I could stop here with you, dear reader.

What Started This?

In late 2018, I was one meeting fresh of being a “Committee Member”. Brimming with ideas from my first real interaction with the Committee and incensed by community problems – some listed in my second ever recorded conference presentation – I endeavored to tackle lots of “we should clean this up” problems. On that list was putting references inside of std::optional. I only spoke to a few people at C++Now 2018 about the idea, and they nodded their heads and said “this is a solved problem, we should fix it”. If only I had asked the right people at C++Now (literally, just one question at a lunch or break!), I would have known that this was not the case. Of course, there were additional warning signs that I was about to walk into one of the most one-sided fights of my life.

A Deafening Silence

After attending your first Committee Meeting, dear reader, you get access to what is called “The Reflector”. It’s a fancy name for “private e-mail lists for Committee Members to discuss technical stuff”. Post-Rapperswil I joined the Reflector, verified my access, and then posted my very first message on the Reflector to some 100+ people:

Dear LEWG,

I am doing some research on optional references…

Nobody replied.

“It’s okay,” I told myself as I swallowed down my anxiety. “I’m just new and they just don’t feel like talking about it to a newbie about this stuff; there’s a long paper trail after all.” I sent another follow-up e-mail six days later, stating the intent of my research and a link to a survey. Again, my e-mail was met with the sound of my own increasingly shallow and worried breathing, albeit it seemed like they had received the post because some survey results trickled in. I was perplexed and confused. Despite probing a few people here and there to verify did my e-mail actually send?!, I received little to no information about why everyone was so quiet… until a sudden DM later after the survey was published:

… Thanks for pursuing this. Regardless of what comes out, it’s a worthwhile effort and it’s probably going to be brutal.

… Uh. Excuse me?

“brutal”

Ha! If only I had known that the descriptor ‘brutal’ was, in fact, taking it easy on me. In doing my survey, I journeyed to the dark and unlit places in C++ and gathered information:

I completed the survey with just shy of 130ish participants. 110 responded to the survey directly, 20ish people and companies – including the original author of Boost.Tuple, Boost reference_wrapper, std::reference_wrapper, and more – replied either on a public mailing list to certain pieces / direct inquiries, or VIA private e-mail. As I reviewed the results, a steady drip of indignation slowly filled me. The reason, dear reader, was that I had been lied to. Everyone was lied to for at least 13 years by counting to the November 2018 San Diego meeting, and nearly 15 years to today’s very date.

The View from Above

If you read the technical paper, dear reader, you’ll see a detailed writing about the two most prominent directions that are always brought up when someone talks about references in X-or-Value style wrappers like expected, variant, and optional. There are actually four directions in total, but we will use the two most often discussed: the “Assign-through” optional direction, and the “Rebind” optional direction.

To illustrate this, observe the following snippet:

#include <optional>

#include <iostream>

int main (int, char*[]) {

int x = 5;

int y = 24;

std::optional<int&> opt = x;

opt = y;

std::cout << "x is " << x << std::endl;

std::cout << "y is " << y << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Some people will shout from the rooftops that x and y should be 24 (the optional “assigns through” itself and into the referred-to object). Others say that x and y should be 5 and 24, respectively (the optional “rebinds” to another object, like std::reference_wrapper). This “ambiguity” of potential semantic choices led to a figurative holy war breaking out in not only Boost when this was first proposed, but in the Committee when it was brought up again. Back almost 15 years ago from today in Boost, Fernando Cacciola – the originator of Boost.Optional – had this discussion and debate. The full discussion – if you hunt down all the pieces – was over 100 e-mails long and featured some of today’s prominent (and today’s currently retired) C++ giants like Alisdair Meredith, Beman Dawes, Eric Niebler, and others.

The decision Boost made earlier was that optional<T&> should rebind. This was based on a fact that Jonathan Müller observed over a decade later in his talk Rethinking Pointers and more explicitly in a blog on his opinions on optional<T&> and why assign-through was the wrong behavior:

Now some people think that having that behavior in the

operator=ofoptional<T&>itself is even a possibility they need to consider.It isn’t.

It absolutely isn’t.

Ignoring any other counter argument, those semantics would lead to confusion as

operator=would do completely different things depending on the state of theoptional!

And he’s right:

void function (std::optional<int&> maybe_obj) {

// blah blah

// work ...

if (some_condition) {

int better_obj = ...;

maybe_obj = better_obj;

}

// blah blah

}

Imagine this code has a value for maybe_obj in the 95% case. You test it and it works for the cases you care about. Then, one day, some_condition becomes true and maybe_obj is empty; the double-whammy you never prepared you or your code for. Well, now you have a dangling reference to better_obj inside some_condition, a problem that is rarely discovered because you might use it in the time before the value becomes some wild overwritten garbage and still just “happens” to contain the value you like anyways and ships just fine. It’s a dangling reference to a stack variable – a vulnerability waiting to happen – but it compiles, runs, and ships.

In a rebinding world, that code is always wrong, and always gets rejected. Not by the compiler, no, but by Code Review, the upcoming -Wlifetime, and other tools. Static analyzers can sniff this in a heartbeat and issue a hard error, telling you to fix your mistake. If you have any degree of code auditing, testing, or checking, this will blow up right quick and can always be flagged down as “this is wrong, stop”.

In an assign-through world, dear reader, no static analyzer can diagnose that code with 100% certainty because Maybe That Is What You Intended But Why On God’s Holy Green Goddamned Earth Would You Write Code To Do This?! But there is an even more sinister way of writing this that looks correct, smells correct, and behaves mostly correct until it does not:

std::optional<int&> cache::retrieve (std::uint64_t key) {

std::optional<int&> opt = this->get_default_resource_maybe();

// blah blah work

auto found_a_thing = this->lookup_resource(key);

if (found_a_thing) {

int& resource =

this->get_specific_resource(found_a_thing);

// do stuff with resource, return

opt = resource;

}

return opt; // optional says if we got something!

}

In both an assign-through world and a rebinding world, this code works. Unfortunately, they work in different ways. In the Rebinding world if you do not have a cached default resource, assigning into opt will re-point to resource. It also happens if there is a resource, too, taking opt and rebinding it to point at the specific resource in the found_a_thing conditional.

The empty case is the same for assign-through (it rebinds, because there is no other option). But if you have a default resource, then that resource will be overwritten by the assignment. This is by far the most sinister bug: subtle overwrites of default resources for seemingly innocuous code that is, by a decent eyeballing of it, non-offensive. Not even a static analyzer can tell you this isn’t what you meant to do. And yet, it is the thing that bit people who implemented assign-through optionals.

Myself included.

A Personal History Lesson

To go forward and talk about the magical unicorn that is assign-through optionals, we must first look backwards.

In late 2013, after a series of lucky events, I exchanged e-mails with an astounding library implementer. Back then, I was absolutely more (fortunately more??) oblivious and way less smart than I am now. I asked for compiler riddles and other things, to improve my skills by being exposed to real-world, first hand shenanigans that people ran into with the compilers they used. As part of this self-driven training with The Great Library Implementer, I saw the proposal going around for optional<T>. I implemented it, and e-mailed it to them. After getting feedback about things I had never considered before (like “protect against self-assignment”), I decided it was time to put my implementation to the test.

I used it in building my Computer Graphics final, a ray tracer.

Putting my Code Where my Non-Existent Rhetoric Was

Complete with a custom engine for both Direct X and OpenGL, I built a ray tracer with the most cutting edge and spiciest C++11 I could muster. Personal implementations of everything that the proposals had at the time (like buffer_view<T, N> – where N == 1 made it like std::span and N > 1 made it behave like the proposed mdspan) made me write code that actually read like the book algorithms and was simple to understand. I had a multithreading block-based ray tracer, but a strange bug showed up. On single, non-complex objects (circles, boxes, the typical “Cornell Scene” stuff) it worked. But when I used complex models or multiple objects, somewhere in the middle of the raytracing the colors would freak out completely. I developed a whole suite of debug tools, made a built-in magnifier to inspect pixels in real time as they were traced and built up, implemented hard freezes so I could stop-the-world and check everything, poured over all the math 6 times over… I could not figure out what was going on. It looked like things just… just warped themselves!

Bug Hunting

I’ll tell you, dear reader, it was bad.

At one point, I doubted that I was even calculating my projection matrices correctly. It was so bad that the Lounge<C++> made a meme out of me: to this day, I am forever the person responsible for all failures in all projection matrices. But it wasn’t my matrices, my ray casting, the color calculations, or the reflection checking. It was then I noticed that some of the object’s materials did not match the models or what was specified in the Scene Format File post-render…

Huh?!

The materials were correct on start, but the values of the materials became incorrect at very specific times, and only in multi-object or complex geometry scenes. My mind collapsed in on itself, fingers typing away madly at all hours of the day. Finally, a week and a half into this infernal struggle, I forced myself to take no shortcuts. My Visual Studio left-side margin was an army of red circular break points, all over the BVH hitbox and material code. It was the last place to check. The error was here. Somewhere.

Did I overwrite some memory? This is what I get for using pointers. My BVH code was so complex for space and speed, implemented off some research papers on the subject at the time, assuredly I was doing something wrong. Writing some rogue values into my materials through UB, maybe…! I am but a wee babe, how could I ever have aspired to wield such dangerous tools like the professionals? Where was I overwriting the materials? Was it my threaded code, writing into rogue memory spots and invoking UB? Was it because of threads? I implemented a single-threaded renderer, and abstracted my code to be able to use either or depending on some startup values. I could feel the nasal demons, scraping at my sinuses with every new fear of Undefined Behavior.

Finally, I got to the inner core of a routine that handled ray tracing, the first one before the entire scene looked like it failed to pass through a warp gate. Thirty minutes of checking every pixel of a 2x2 multi-sampled 1280x720 image.

It was my optional.

Congratulations, I Played Myself

See, back then I was not blessed with the Lovecraftian knowledge of C++ that continues to uppercut my jaw, even today. Even after the November 2013 CTP ruining my day several times a day while working with Rapptz on the first version of sol, I still trusted library specification and paper specifications over my weak knowledge. I implemented buffer_view<T> to specification and it worked wonders: was std::optional<T> not also perfect? boost::optional had support for references, so just follow the specification for std::optional<T> to the letter but with mild adjustments for the fact that I was storing a reference. This let me have code such as optional<Material&> hit(const Ray3& ray) { ... }.

The ray casts into the scene that missed returned the “default background material”. That’s fine. I had reflections, so I watched the rays bounce off the first object and then bounce again to the environment, but it was just the default background material, so that’s fine. Then, I watched in slow-motion horror as I shot a ray into a complex scene. It bounced once. Then again. And again. And each time, I assigned over the pre-existing optional<Material&> returned by a previous hit call. At the time, I did not know what “assign-through” or “rebind” was. I was just doing what the paper told me to. What the interface told me to.

How naïve of me.

My optional<T&> – by following the specification of the normal T from the Standard’s paper and just doing the literal “how references totally should behave!” implementation – assigned-through. I did not know this or understand this, but that’s what the words on the paper were telling me to do.

I assigned over all sorts of materials in my complex geometry scenes due to reflections. Over and over and over, each pre-filled optional another target for the recently-returned reference from my (thankfully correct) BVH code. Like so much chaff, each engaged optional was plowed over the others. Phong models changed, texture IDs were stolen, colors were paved over like Eminent Domain was in style. I had found my problem. optional<T&> was, in all my code until that point, empty or only written to once. When first constructed and when assigned from an empty value, my assign-through optional always rebound. It created an inconsistent mental model. And the moment I took it beyond its simple uses – beyond the simplicity of my basic scenes – that mental model created from experience broke down completely. There was no consistency for a nullable type for the semantics as I had understood them from the paper.

I didn’t e-mail the library implementer back about this particular detail from using my optional. I kept my deep embarrassment to myself. When I checked boost::optional<T&> it just rebound. It was me that was the problem. I was just a dumb dumb: how dare I try to implement what the Boost and Standard Library Gods of today had already done, but without the specific attention to detail necessary to understand such a nuance?

In 2013, I had no idea how hard Fernando Cacciola had fought for exactly this behavior: it was simply as it was, set in stone by the Powers of Boost and C++. I hung my head in shame and did not read those standard papers again. Clearly, I was the one who was not ready.

The Wrong Assumption

From that, I never looked back to assigning through to the reference. Why would I? Boost had gotten it right, assuredly the Standard would too. But it didn’t. And so, years later wearing a suit and a tie, I stood at C++Now 2018 and talked about the optional<T&> for sol2. I expressed my great perplexity at how the Standard could leave out this critical infrastructure. I resolved to write a paper, and get it right for everyone. Nobody should have to do suffer the same silly mistake I made, the same bug hunting,

the same crushing humiliation.

But people insisted that std::optional<T&> could very well assign-through and that it was a good, consistent thing. My mistake was from 2013 and was from an inexperienced novice with poor understanding of C++. I assumed that my experience was invalid and that the Committee was objectively correct. But, just to be sure, I set out with that survey I mentioned earlier to find evidence supporting the Committee’s stand-still over this. It was only as I gathered the result that indignation rose in me.

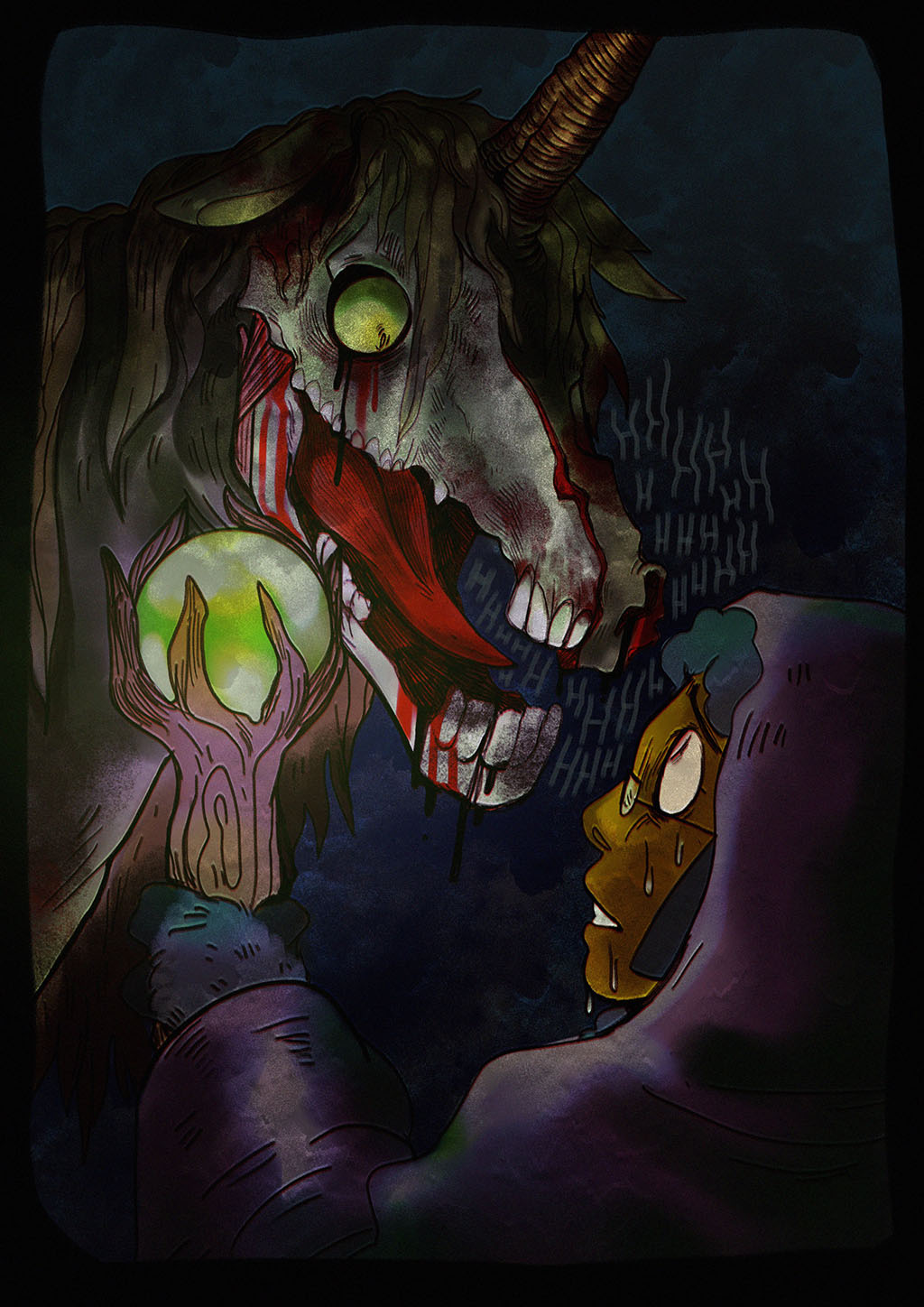

Assign-through? That magical, majestic unicorn that I swore I could find even in the darkest corners of the C++ World?

It. Didn’t. Exist.

Oh yes.

Soak it in, dear reader. In a nearly 15 year period, under “intense scrutiny” from C++ experts all over the world over multiple shipped standards, nobody noticed – or nobody cared to notice – that the people who claimed that assign-through optional references were “consistent”, “the obvious way to do things”, the “contentious, completely valid other choice” were fudging it. We were debating a magical unicorn that did not – and dare I say, maybe never – existed on any scale larger than a private C++ hobby project.

Out of the 110 people who responded to the survey, only 2 people said they had a reference-capable optional with assign-through semantics. Except, the first person admitted they never put a reference in their company optional-like Maybe<T> type, because they never added support for it and it broke the build if they dropped even an int& in the type there. That left one person using a fully implemented, reference-capable assign-through optional in their long-term C++ hobby project.

One of the previous poll questions showed an almost exact 50/50 split between whether assign-through or not assign-through should exist for a hypothetical optional<T&>, with a handful of folks saying “neither, everything should be explicit” or “just use pointers”. Fantastically, next to none of the people voting for and writing about optional references or indicating their dream optional with support for assign-through ever implemented or even used someone else’s implementation.

Let that sink in for a little bit.

A whole community – which prospered from boost::optional<T&> and its design choices for years – was being told that an unimplemented, unproven design that nobody worked the kinks out of was worthy of standardization.

Deep Breath

That a – in Plain English – bunch of zealots and demagogues could argue for a thing they have never had any proper implementation or deployment experience with and fool the entire ISO/IEC JTC1/SC22/WG21 C++ Programming Language Committee for 15 years is a Comedy of Engineering. It is a farce so profound I do not have enough laughter to express my profound incredulousness in every single person who participated passionately in this twisted masquerade. The worst part about this is that I, in trying to make sure I had not messed up, did a second implementation of assign-through and that damnable survey to truly understand if I had missed something. “If the Committee is pushing these ideas, assuredly this assign-through technique – despite all research, exploration, and community indication to the contrary – must have some merit!”

That could not have been further from the truth.

Everyone except the assign-through pundits on the Committee had done their homework. Nevin Liber spent literal ages working with variant and optional to build consensus, and he gave a long talk about how hard he worked. Matt Calabrese disagreed with both assign-through and boost::optional-style rebinding and put his fingers and keyboard where his ideas were and actually both implemented and presented at conferences about his ideas. Proponents of “pointers are optionals” at least have some existing practice and APIs to fall back onto as demonstrations for the successes and failures of their design choices.

Assign-through had no concrete anything, and the people who did do the work – like myself and that one lone person out of 110 in the survey – participated in good faith while people who had no intention of being fair or honest waved a single code snippet in everyone’s face and spooked the entire community about references in types like variant, expected and optional. Others who did not like assign-through still saw it as a means to an end: they wielded the same utterly disingenuous rhetoric. They wanted to leave it as a pointer, or they wanted to only have value-only wrappers, no reference, etc. etc.: as long as optional references remained in this supposed moral deadlock, they would never have to discuss or reason about the benefits or inadequacy of their approaches.

I fell for it too like an idiot with p1175.

“Just be Neutral”

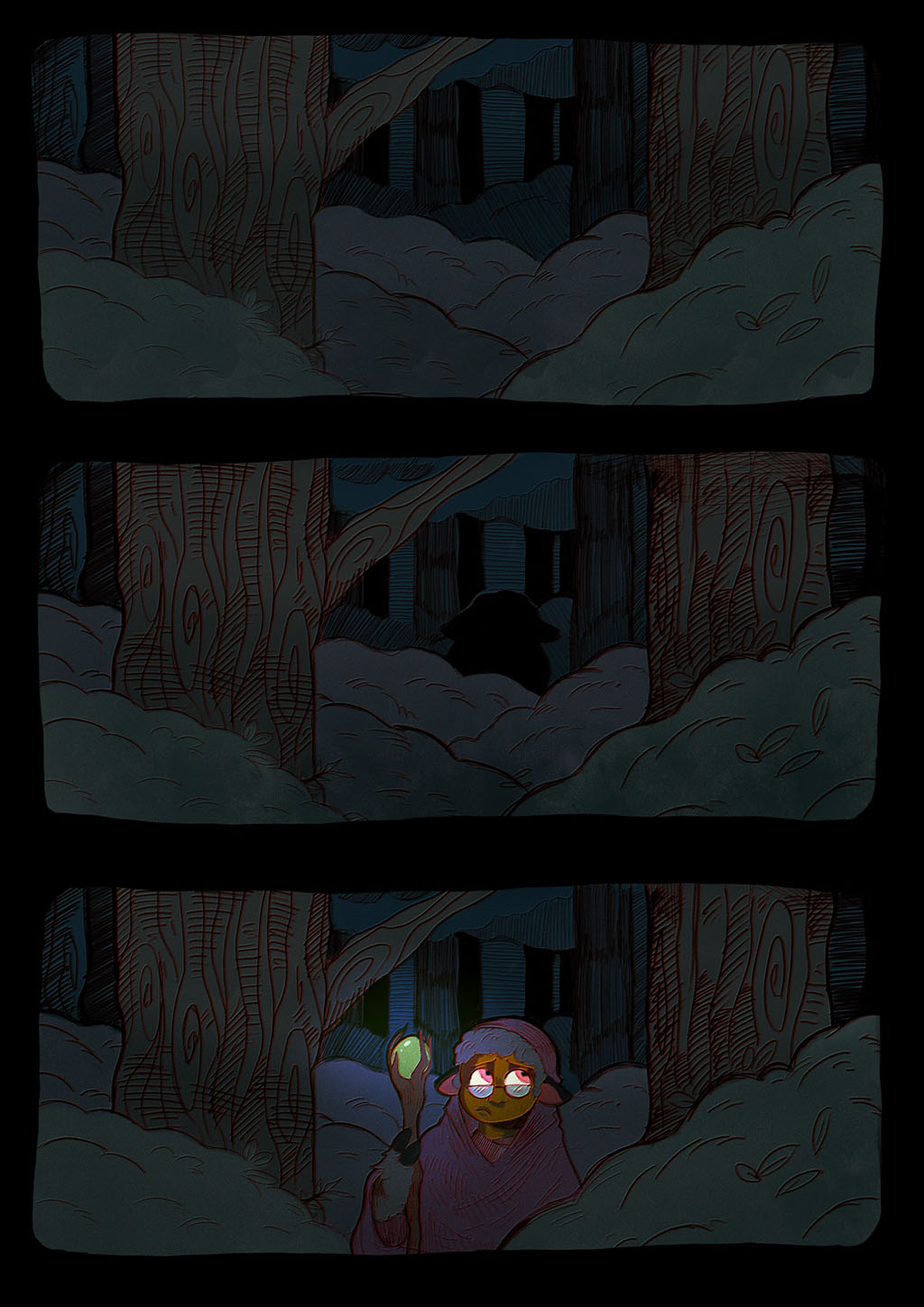

Everything I am writing now, I knew before I walked into the LEWG room during the November San Diego 2018 Committee Meeting. I knew this Unicorn never existed. I knew it was just an illusion. And yet, as I gazed upon my research, I realized that even if assign-through never existed, the pontificating and posturing over 13 years served as a ritual. And from that ritual and the sacrifice of Due Diligence, the Committee spawned into this world an unholy aberration. Composed solely of an undead idea, this thing became its own force of will and grafted itself together in the shadowy corners of our blind faith in others.

And I was filled with anxiety and fear.

Scared and afraid of the Committee and what a big divisive paper might do, knowing we were duped out of a proper std::optional by an unchecked lie, and yet not wanting to “burn bridges” or “ruffle feathers”, I sent e-mails to a few Committee members and Directly Messaged others. I showed them the paper early, I explained my fears and uncertainties: I wanted to quell any indignation, however righteous, and present the paper in the best light. And in this Committee Newbie,

they found an easy target to propagate their ideas and agendas on how to interact with the Committee.

“Don’t go too hard.” “You’ll ruin it if you go in guns blazing.” “Just take the neutral option.” p1175 was not the paper I wanted it to be: it was the result of those e-mails and DMs coming back with that singular idea: don’t rock the boat too hard. For the sake of acceptance, I not only emaciated and emasculated my own paper: I took out the research, data points, survey data, and left nothing but a hollow husk and shell behind. A weak, watery compromise of a paper driven by doe-eyed compliance and cowardice. I betrayed my instincts, padded my fists, painted a smile on my face, put a frail bend in my back, and poured water on my brightly burning hunger for rigor and completeness in my work.

In the dark, I knifed my integrity of work in the back, whispering praises to the others’ devotion to neutrality and compromise.

Obvious hindsight is obvious: this was not the way forward. I fell into the exact trap that Bjarne Stroustrup warns about in a few of his papers, including the Direction Group paper. I walked into the San Diego November 2018 meeting and LEWG called for my paper. With my gutless smile and my wringing hands, I made nice and played meek.

It was like walking with an armful of flowers and a box of chocolates into a machine gun fight.

Old and ancient complaints decimated what feeble arguments of extensibility and compatibility I put forward. The talk of optional<T> being Regular came up again and again, despite optional<T> not creating anything more regular about the underlying type but simply forwarding and deferring to the base type. Even vector<bool> was brought up, that abhorrent poster child against template specializations thrown around frequently. More than once I was ready to fire back… but then I remembered. No data. No research. I had gutted my own paper in the name of Consensus and Status Quo. I mumbled and shuffled, my own fire extinguished by the extent of my inadequacy and how badly I had fooled myself in the name of neutrality. At one point, I was asked “where’s the paper that [p1175] references? I would have preferred that one…”

I was a fool.

Quitter

“I withdraw this paper and I will not bring a revision; someone else can take it.”

Just like that, I stopped playing the game. Metaphorical tail tucked between my legs, I let the “consistency with the language” and other tired, porcine arguments – fat with misinformation and metastasizing all over the C++ Community – go unchecked. I went to sit silently in the Core Working Group room for a good portion of the San Diego meeting to lick my wounds and sulk. It has been over a year now. “Maybe for C++23”. “No consensus for change but not outright rejected”. Soothing balms for my festering wounds. That experience cost me greatly and dearly, in self confidence and beyond.

But it cost the C++ Community at large something even more.

The Invisible Hand

The C++ Committee likes to pretend that its arguments, inaction, and inabilities have no effect on the greater global ecosystem. Very frequently we talk about not disturbing what is currently done in the industry, and not breaking compatibility or existing code. Often times, this is true. But there was no time when the so-called “neutral” option the Committee took with std::optional – by removing reference support and deferring it to a “later date” – was a neutral choice.

Big and small companies and code bases paid for the deadlock we projected over this.

Because the Committee gave an unfair legitimacy to a non-choice, that decision rippled out into the community and infected ecosystem. To quote Clang contributor David Blaikie:

…

So I don’t think it was some explicit choice not to support it - but a lack of need & probably by the time folks (such as myself) were talking about whether it should support references, there was enough open discussion about the trade-offs/complexities of supporting them (thanks to the committee discussions, etc.) that there was probably at least a little hesitance - likely enough to err on the side of “let’s just keep doing things the way we have and use raw pointers for ‘optional rebindable references’”.

But this was only one of the more innocent changes. The survey revealed that the stoppering of optional reference support cost people money, time and pain. In response to the “If you ever had to port from one optional type to another, any porting troubles between optional types or similar?” question:

Had reference support before upgrading to std::optional, porting those to pointers was quite some work…

boost::optional/ custom optional tostd::optional. Trying to migrate toT*proved to be a nonstarter for many parts of the codebase because of the way arguments were passed to the code: it would require a lot of not only API surgery, but call-site surgery as well.

No. I avoid

optional<T&>like the plague, and just use it the vanilla way; there are no pitfalls there.

gave up trying

Gave up trying indeed, friend. But you’re not the only one to go with the Committee flow. From Martin Moene’s optional-lite to Isabella Muerte’s mnmlstc::core, people all over defaulted and folded to the Committee choice in the name of standardization:

optional-lite is just meant to be a rendition of std::optional

exactlyas is presented in later optional proposals and C++ IS insofar possible given the standard it is used under.

I’m the creator of MNMLSTC Core’s optional, and it originally supported references but when the committee killed them off in the proposal, I removed it as well since I wanted 1:1 parity with the standard. I’m 1000% in favor of rebinding optional references!

By the time of my survey, others heard the Committee’s planned uncertainty about optional references and its “too many valid implementation choices” explanation:

PROHIBITED

optional<T&>as utterly confusing, and BTW this answer SHOULD have been in the survey from the very beginning

Still, at least some others had more sound design decisions for why references of optionals should not exist:

tombstone is needed. most of types has spare parts to implement invalid. so

optional<T, optional_traits<T> > {}is good idea. never, ever wantoptional<T&>, or anycontainer<T&>(includingtuple<T&,U&>). Reference are for parameter passing & returning purpose. For storing purpose use value semantics likeoptional<reference_wrapper<T> >. perhaps give a short standard alias toreference_wrapper

Much of these I have spent time in the technical part of the above-mentioned d1683, discussing what they are and why they end up being poor choices in practice and implications it can have on wider system architecture. Of course, one person was like me in 2013:

I don’t think there were any unusual implementation choices

… Oh my sweet, sweet summer child.

Where do we go from here?

I don’t know.

My job here was to lay out my knowledge and experience bare to you, dear reader. As I promised the Committee in the November San Diego 2018 meeting, I will not be bringing another paper forward on this subject. The sheer lack of self-reflective ability of Committee members sticking almost blindly to a preferred style or guidance without research or investigation, that horror of a Unicorn imagined up from no implementation or deployment experience, and the sheer lack of rigor in exploring the situation while still making decisions that impact the entirety of the C++ Community is beyond baffling and deeply troubling.

At least we have people like TartanLlama, willing to make high quality implementations against Committee thought for a design they thoroughly researched and verified themselves.

I can only wish you, dearest reader, Professor Peter Sommerlad, and MISRA C++ the best in this entrenched battle. You will not wrestle against flesh and blood. Yours is a battle of changing the direction of a community, poisoned from a high place by those who skipped on the Engineering portion of their Engineering work. You will stand against a Regular Status Quo. In whatever decision you make, be diligent. Take my research, your research, and your experience to heart, so that you may speak boldly, as you ought to speak. May your cause be blessed,

and may it bring comfort to your hearts. 💚

P.S.: With my Greatest Thanks to the talented and wonderful artist Anett (@WusdisWusdat), whose terrifying art brought a tangible form to this lingering, festering psychological plague inflicted upon me and let me face up to what had been done. Buy her a coffee, y’all, or just pay for a slice of her pretty amazing artwork.