This is going to be a practical overview of how I reduced the compilation time and binary sizes of Release Mode (-O3 or /Ox) C++ software. The goal of this will be to review some of the things that help with the goal, and some of the things that C++ as a language is fundamentally incapable of producing satisfactory answers to. Let’s dig in!

The Final Savings

We were able to save some things for a project with 2.5K class bindings:

| Version | sol2 | sol3 (patron-only alpha) | sol3 (now) |

| Build Time | 2 hours, 3 minutes | 2 hours, 11 minutes | 1 hour, 53 minutes |

| Binary Size | 119.0 MB | 138.0 MB | 103.0 MB |

Wait… what happened in the middle there?

I added 3 new core template types that all abstractions get milled through. I also committed some of the sins below in improving the functionality and streamlining the code. To be honest, I’m actually surprised it only cost me 7 more minutes over sol2! But, let’s talk about the things I did in order to get to where we are now, and what I needed to identify as problem points…

The Methodology

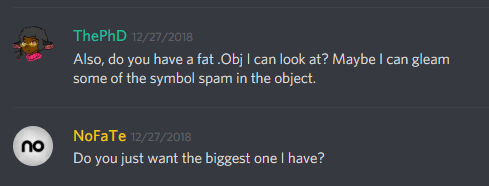

This was a combination of intuition and empirical evidence. I had suspicions about what increased my compile time, but I did not want to go off on a wild hunt trying to figure out what was going on. Much as Templight and other tracers exist (and are currently being worked on) I kept my assumptions in the back of my mind but checked them by asking a few companies and individual users of sol2 to send me their largest object files VIA Discord and other means:

In doing so, I could confirm my suspicions by seeing what was serialized into the object file. Note that while this does not perfectly translate to the final code (especially in release builds), it is a good proxy for (1) link times, due to having to resolve all of the (possibly non-unique) definitions from a single object file with all the others in the project; and (2) compile times, because the compiler has to vomit all of this stuff into these object files to begin with.

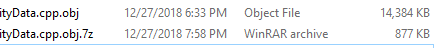

One of the object files I studied was 14 megabytes big from a Visual Studio 2017 Release build. the fun started when I expanded the .7z file:

Mama mia that’s a spicy 16.4x file size increase!

This is a screaming red flag that we have a LOT of redundancy (because it compresses so obscenely well under default settings). Duplicate symbols are rife in any TU that heavily uses templates, and sol3 is a template-heavy, header-only library. But, this probably doesn’t explain the absolute ballooning in size when going from the packed 7zip I was sent to the big thing in the actual binary.

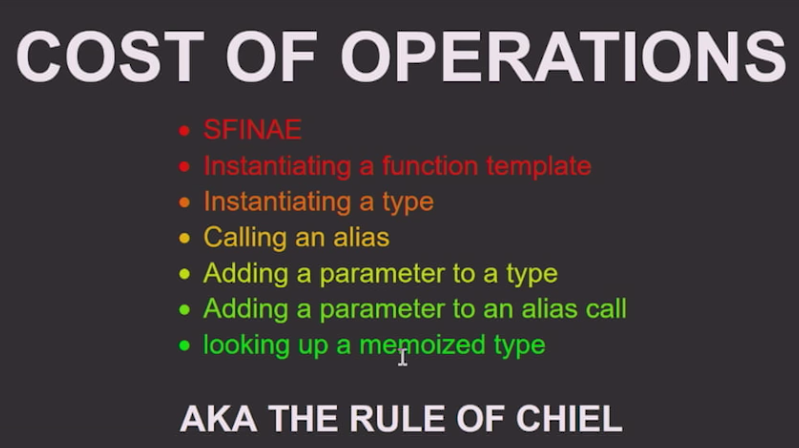

To help me dig in, I relied on someone else who did all the hard work for benchmarking what were the more expensive operations one could perform in relation to templates. I also use this brilliant person’s Rule of Chiel:

Armed with this knowledge and a bunch of object files, I set off to find the worst offenders in my code. I targeted what was either SFINAE + types, or SFINAE + function templates, since those were my typical things that destroyed my code. sol2 uses a lot of struct specialization SFINAE, which is probably the most damaging to compile-times right now. Coupled with some very gnarly function template SFINAE and other things, I figured that this and other things were probably the root of the cause.

Just where I found that bloat – asides from the obvious places where I used exactly those techniques – was even more of a surprise…

Easy to Write, Easy to Read, Easy to… Bloat?

Lambdas are ultra convenient and – in some cases – even more powerful than structs you declare locally (for example, you can’t template function-local structs but you can do it with a lambda and auto/Concept function argument types!) But, I needed to tear them down in several places where I had capturing lambdas inside of templated code. I only did this in a handful of places – 6 or 7 total in the whole library, up from 1 or 2 in sol2 – and it did a fair amount of to save me the mental overhead when programming. They’re just Immediately Invoked Function Expressions, right? How costly can they be?

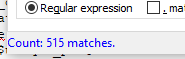

It turns out capturing Lambdas – even entirely local ones – don’t optimize out cleanly in terms of code size for C++ and a lot of it gets dumped into the object file and the resulting executable. I used dumpbin to get me all the symbols in a text file (an 11 megabyte text file) and then proceeded to just goof around and scroll through it. Some things there was nothing I could do about, like all the string spam for my Compile-Time Type Strings work I was doing. But, for this 1 object file where only 1 class was being bound using an alpha of sol3, I ran a count for the times lambda showed up:

Sheesh… a few more pointed searches for certain identifiers with the lambda revealed that most of those belonged to my detail namespaces and inner workings. Remember, this is just for binding one class! All this symbol spam from the template-capturing lambdas revealed one thing, though: each lambda, when inlined, results in a fat slab of code that is different per-instantiation (I mean, duh, that’s the point of a template, right?). The compiler marks all of this code inline and dumps it into the resulting function instantiation, which is expected. The problem is that capturing all the variables in a templated function means that any time you have enough variable initializations and function declarations that depend on said templates, it is impossible for the optimizer to combine these bits of code together, even if its fundamentally the same code for all invocations!

The solution here was to roll up my sleeves and get out the dough, because it was time for…!

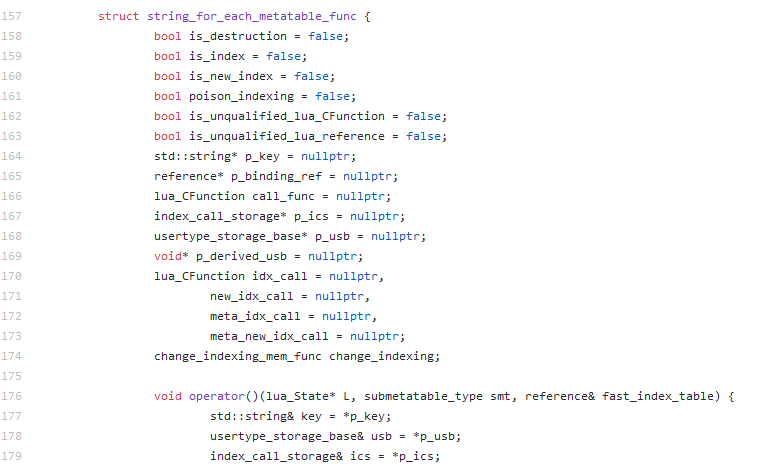

Since the 1990s, like your mothers and their mother’s mothers, and your fathers and their father’s fathers, I took to the oven to bake only the freshest lambda to trump them all, taking advantage of the fact that all of the routines were identical and that I could use some of Grandma’s void* and Great Aunt Mary’s function pointers. To top that off, Lua is a runtime ingredient so all the compile-time shenanigans weren’t exactly necessary at the point of my lambda. I lowered down my if constexpr spices into regular if statement herbs, powered by runtime booleans initialized with constant expressions. The result was a creamy yet spicy French struct with so many delicious members. Ultimately a reduction but the culinary blend saved me quite a bit of symbol spam in the object file and lambda-based template spew by quite a bit, making for some chef kiss nice improvements:

Food silliness aside, this helped a lot. To recap the point in a more clear way, though, here are some snippets illustrating the various degrees of (non-)trouble you can get yourself into.

Good:

void func () {

auto iife = []() {

/* work */

};

iife();

}

Also good:

void func (int arg, my_class& foo) {

auto iife = [&]() {

/* work */

};

iife();

}

Okay, but be careful…:

template <typename T>

void func (T arg, my_class& foo) {

auto iife = [&]() {

/* work */

};

iife();

}

Worse:

template <typename T, typename... Args>

void func ( my_class& foo, Args&&... args) {

auto iife = [&]() {

/* work */

};

iife();

}

Screaming in the distance:

template <typename Binding>

struct binding {

template <typename T, typename... Args>

void func (my_class& foo, Args&&... args) {

auto iife = [&]() {

/* work */

};

iife();

}

};

Of course, this is easy to see in these examples. But when working with complex template functions, it’s very easy to just make a fully-capturing lambda that gets you all the local variables and arguments you need with very little fuss. Just be careful if it’s a common use point in your API, and especially if there is a forwarding capture reference and you are expected to have string literals come into your API. String literals are actually the worst offenders for the bloat, because "set" is not the same type as "super_set" (they’re both different-sized C-style arrays).

Having a (imaginary) std::c_string_view or some std::string_literal constexpr type be the default here might help that out but I doubt the C++ Committee will ever bite on a std::string_literal-by-default type anytime soon. (After all, backwards compatibility etc. etc. – someone is bound to be broken if we change the fundamental type of "blah" in C++!) But, what may happen is a std::string_literal type that can only be created magically by the compiler. This will give us some interesting information to work with (read-only, string is interned, etc.), and from there we could probably at least fix some of C++’s strange warts, even if we still get const char[N] and const char* from template deduction and auto-deduction.

The point being, if you expect my_template_f("blah") to be a thing your users write, be careful!

Forward Declarations and Headers

Is anyone really surprised this shows up?

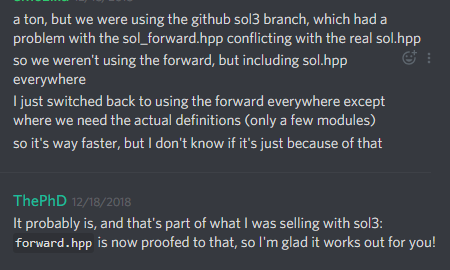

Parsing stuff in C++ is its own particularly special nightmare. I provided a sol_forward.hpp to ease on this parsing adventure. But I didn’t really put enough stuff in there. So I added some more forward declarations in there for sol3, and now the single header generates a proper sol/sol.hpp and a sol/forward.hpp for users to include. The result was pretty good gains:

Forward declarations are good. Honestly, we should probably be providing very small Modules for the standard library, and also be providing incredibly fine-tuned headers too. <functional> alone is absolutely enormous, and it would be nice if we just had <functional_fwd> when we really don’t need the whole thing. I have some ideas in this space, but it’s going to take some time before I can let it manifest. (I have a lot to do over the next 3 years…!)

Culling Tag Dispatching Overloads

Tag dispatching – while a good technique – results in the compiler having to pick between overloads, even if its only 2. The worst part about any overload set is that the compiler cannot short circuit what it finds: it needs to walk over all of the possible function entities in an overload set before selecting the right one.

My tag dispatching code was mostly tree-based, computed from picking one of 2 branches using std::true_type and std::false_type

template <typename T>

void branch(std::true_type, T data) {

// execute on true

}

template <typename T>

void branch(std::false_type, T data) {

// execute on false

}

template <typename T>

void compute(T data) {

// pick branch,

// only one gets called for `T` thanks to

// template overloading

branch(meta::is_fooable<T>(), std::move(data));

}

This makes not only instantiating the right function template but selecting it (as most tag dispatches are within templated functions) expensive. It’s less expensive than raw SFINAE on function templates but it’s still expensive. if constexpr doesn’t work well when you have separate paths of code whose conditions are not behind templates (remember the condition has to be part of a dependent type to have the compiler not fully parse and semantically check that branch). It works wonders when you do have a template and you can gain a lot of benefit by taking what used to be overload sets and changing them into single function (template) invocations. Now you are only paying the cost of instantiation, and not the cost of overloading several entities you’ve defined!

This is a lot simpler to do and probably makes the code much easier to read as well. It’s only available for C++17 but I do not mind increasing the compiler requirements for sol3! Especially since all 3 major compilers are free at this point, with MinGW-w64 serving up the world’s easiest-to-use installer. Albeit for some reason it still doesn’t ship a regular make.exe-named executable, but rather some weird mingw32-make.exe thingy instead. It’s amazing how much tooling this breaks… I have to add a mklink make.exe mingw32-make.exe, usually.

I digress!

7 years later: Tuples and Recursive Variadic Templates Run Amok

They are still a problem, and nobody is surprised.

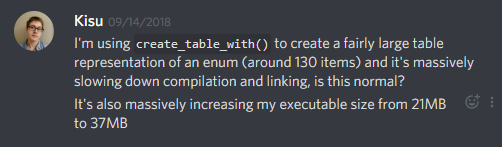

In my race for compile times, I had a number of places where in C++11 and C++14, I was forced to use a recursive variadic algorithms or use tuple tricks. This proved grossly untenable because tuples and the things there in do not scale beyond even 25 elements. Take, for example, my variadic create_table_with, which just created an empty table and then packed everything in a big ol’ tuple to set with:

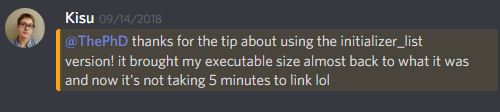

Removing recursive tricks to use tuples + fold expressions didn’t help. In the end, I had to provide a second overload for new_enum that took only an initializer_list<std::pair<std::string_view, EnumT>>. And, of course, it worked like ✨ magic ✨:

I suspect that a 130 argument (x 2 to name each key, so actually 260 argument) instantiated variadic template function is big, but let’s be fair: the compiler reduced both the executable footprint and the size with the same information but in an initializer_list. Part of this is because we mashed down what was 60+ different const char[N] from string literals of different sizes. Another part was because we were not instantiating a 260-size tuple in the initializer_list version, then destroy that said 260-element tuple and forwarding each const char[N] and enumT pair into a single set call where a hell of a lot of work is done. Just not having to do 60+ different instantiations for a bunch of different-length string names and one enumT is pretty great, already!

Still, it’s not as if the thing is entirely escapable at the moment. When you cannot pin the types down for an initializer_list, you need tuples to interact with patterns in your variadic lists (pairs, “the last of the list”, triplets, every 5th argument, whatever it is). In C++, common idioms for working with patterns and other things are not viable options with variadic packs without doing tuple shenanigans. It is impossible to perform novel algorithms with variadics for more than just utterly pure – e.g. without co-dependency on any shared state between arguments – expressions.

But, with if constexpr we can special-case the simple versions. For example, I have a lot of code that now looks like this:

template <bool global, bool raw,

typename T, typename Key,

typename... Keys

>

decltype(auto)

traverse_get_deep_optional(

int& popcount, int table_index,

Key&& key, Keys&&... keys

) {

if constexpr (sizeof...(Keys) > 0) {

// generic case

}

else {

// tail case

}

}

Or like this:

template <bool global, bool raw,

typename Key, typename... Keys

>

void

traverse_set_deep(int table_index,

Key&& key, Keys&&... keys

) {

if constexpr (sizeof...(Keys) == 1) {

// do not do recursion on self or

// call another overload:

// actually set the field and

// stop here

}

else {

// mumble-grumble, we have more than 1 key,

// keep doing recursion so

// the algorithm works

// or tuple shenaningans...

}

}

The above optimizations save us because sometimes we don’t need to do the recursion or make a tuple, and there’s not multiple functions: just the one. This cuts down on compile times bit a bit more.

This is only a small mitigation, though. (Of all the savings, this technique was only responsible for 4 minutes of compile time and had no Release-mode binary size impact for the project above). Having proper patterns or random-access for my variadic packs would allow me to drastically shortcut all of these tuples or recursion entirely and get them out of the object files and code gen. C++ is cutting my legs here, and my users are expecting me to walk and provide them with both the mystical, magical, beautiful interface plus the compilation speed.

Why not Write some Papers for the C++ Standard?

Others before me have tried and failed to get things I critically needed past the Committee, even with implementations in Clang that proved it was possible to implement.

p0478, a tale of the variadic tail

Let’s discuss this in terms of use cases. For my set algorithm on a table, I traverse a list of keys and where the last 2 objects are a key/value pair for the final set. The rest are just keys that dig into a table (think my_table["a"]["b"]["c"] = 24). This problem would be solved perfectly by p0478. The problem turned out that 2 major compiler writers had template engines that could not handle it very well. Even though they proved that it was implementable in Clang, the template engines of the other 2 major compilers tanked the feature.

Consequently, a new paper that could have also had this feature without much pain – p1061 – also will not be able to provide me with a way to obtain the tail of a pack of things. This is mostly for the same reason as p0478, so we’re still in the weeds here and I don’t feel comfortable asking p1061’s author to tack on a feature that people already voted against in p0478.

p0145: re-establishing user intuition as useful in C++

Another example of getting rid of recursive or tuple-based algorithms just by having reasonable language defaults is p0145. This paper looked at a wide range of expressions in C++ where users had implicit expectations about sequencing and were categorically denied their intuition and expectation. In my particular use case, pinning down the order of argument evaluation would remove the need for my recursive evaluate(f, type_list<Args...>) that calls f with arguments generated in an order-dependent manner from type_list<Args...>.

In looking at the object files I received, evalutor::evaluate<T...> is responsible for another Russian doll-set of compiler template spew for properly utilizing a state-dependent transformation from type_list<Args...> to actual Args&&... args I can invoke a function with. This would Just Work™ without the recursive one-by-one algorithm expansion if arguments passed to function were evaluated left-to-right before invoking the function! Which, by the by, if you read this blog and you didn’t know: yes, C++ does not define the order of argument evaluation. It’s unspecified behavior! Subject to flimsy restrictions.

Proposals to just fix the overall argument order as left-to-right reading order have also been discussed, with p0145 being the last seen and accepted of them. The best part about this paper is that it provided benchmarks and discussed that the optimizer achieved its -/+4% performance changes without any knowledge of the new argument order on the optimizer’s behalf. That means there was plenty of space to do a lot of work to remove the negative part of the range and keep the +4% in code. As a Committee, we had a chance to make a common expectation actually standard. It would have also stopped a plethora of questions about people being confused as to why their function calls had funky argument values and weird results (e.g., it is a common concern, just look it up on any Stack Overflow answer addressing the issue).

The battle was hard fought, but ultimately ceremony and process whittled it down. p0145 was forced to compromise from a last-minute objection in the plenary session where features are officially adopted under ISO blessing. As a conservative fix, the argument order was allowed to be fixed in some order (left to right or right to left, but not interleaving). We sort of just have to sit with this one on our hands now, still. Normally, people tended to make fun of individuals who expected argument order to not be some unspecified soup.

“Code that depends on the order of argument evaluation / expression evaluation is just plain wrong”, many language lawyers and veteran programmers would tell you. And in a way, it was easy to distill this “wisdom” onto the younger generation. Before, people who wanted to rely on the processing of the order of arguments either did stuff with the preprocessor (eww) or just were “being lazy” in a C++03 world and writing “clearly incorrect code”.

Then C++11 came along and made variadics a first-class language feature.

Now with the expansion of variadics – whose syntax and look implies and left-to-right expansion – it is not so clear anymore that the young C++03 and VA_ARGS preprocessor-expansion users were just oddballs or goofballs. In fact, the intuition they had was probably spot-on for most folks who used the language the first time and happened to write code like that.

To dive deeper into my particular use case, take template <typename F, typename... Args> invoke(storage_bucket& some_storage, F&& f, type_list<Args...> args);. It is impossible to have f( pull_args_from_storage<Args>(&some_storage, &temp_order_dependent_state)...); work without a fixed argument order. If pull_from_args messes with some_storage or temp_order_dependent_state in that function, you now have an unspecified sequence order in your code, the same way f( a(), b(), c() ) can be evaluated “call c → call b → a → call f”, or some other non-interleaving way. The solution is to, instead, write a recursive algorithm (or invoke a constructor like for std::tuple to store the temporaries).

Many people tried to convince me that I can write a non-recursive form by

- creating a temporary

mutator<Args>(&storage, &order_dependent_state)...dispatched to an intermediate function - doing

detail::swallow{ 0, (mutators.mutate(), 0)... }(or equivalent fold expression) to callpull_args_from_storage<Args>(*p_storage, *p_order_dependent_state);inside themutate() - store the value in a delay-initialized object, then pull out the internal value and forward it to the actual

fwithf( mutators.get()... ).

This does not work because it is impossible to delay-initialize things without forcing extra moves in the case of values returned by pull_args_from_storage<T>. I can assume an lvalue will be stored somewhere and save a pointer to it. But what about T&&? Consider the following pseudo-implementation of mutator:

template <typename T>

struct mutator {

storage_bucket* p_storage;

state* p_order_dependent_state;

std::aligned_storage_t<sizeof(T)> delay_init_value;

storage(storage_bucket& s, state& ods)

: storage(&s), order_dependent_state(&ods) {}

void mutate () {

new (&delay_init_value) T(

pull_args_from_storage<T>(*p_storage, *p_order_dependent_state)

);

}

T&& get () {

return std::move(*reinterpret_cast<T*>(&delay_init_value));

}

~mutator() {

auto& ref = *reinterpret_cast<T*>(&delay_init_value);

ref.~T();

}

};

Problems to consider with this approach:

- Storing a delay-initialized value

Tdirectly means you enforce an extra construction, extra move, and extra destructor call for this type. If you only construct but don’t destroy and just move the class, that’s a huge bug. - If someone returns a

T&&directly (or you decide you’re going to avoid the problem in item 1), how do you delay-initialize that reference? Remember that references don’t actually exist (even though they do and you can observe and touch them at times), andsizeof(T&&)gives backsizeof(T), which meansaligned_storageor any other size-based delay-initialized storage mechanism is out of the question.

At the very least, I could solve T& by assuming it’s valid and storing a pointer, and then passing along that dereferenced pointer (e.g., partially specialize the struct for template <typename T> struct mutator<T&> { ... };). But how do I store the T&&? Do I just take the address, hope lifetime extension lasts long enough, and then dereference-and-return?

The alternative fix is to use a std::tuple. Unfortunately, tuples are a poor idea in practice, especially on VC++ 2017. Currently, VC++’s tuple is implemented recursively, with some 20+ constructors invoked recursively on itself until it reaches the empty tuple. To go back to the 260 elements from before, that’s quite the Russian Doll of template struct instantiations, all different from each other by the order of arguments…! So I either pay the cost of a recursive template instantiation from VC++ tuple (or roll my own tuple, or take one off the shelf from boost::hana), or eat the cost of a recursive function instantiation to process the arguments in order so I can call the function.

At this point, I’m so burned out on working with “flexible” generic algorithms in C++. To do the basic bare minimum of things requires crazy gymnastics. And meanwhile, I can’t simplify my compiler crunch in the slightest, while other users use sol2, get terrible slowdowns in certain codebases and environments, and then swap to competing implementations that are inferior in run-time performance and feature set but give them a proper build-run-debug loop.

So… what do I do? If C++ has fundamental issues that require these zany techniques and the papers that get me there keep dying, what do I do?

Let’s Talk about Solutions

There’s 1 proposal that is looking to add a way to iterate over either a tuple or what it considers to be a ConstexprRange, p1306.

This proposal is fine (it does not solve my key-value pair patterning problem in the slightest, but at least its trying), but only if you want to work with tuples. The proposal gives me a way to loop over compile-time indices, too, but without the commented line it remains more or less useless to me:

template <typename... Args>

void f( Args&&... args ) {

for constexpr( std::size_t i : std::ranges::iota(0, sizeof...(Args))) {

// THIS RIGHT HERE

decltype(auto) element = language_func_to_get_pack_element...(i, args);

}

}

This is what I want. Not more tuple tricks. Not more compile-time bloat through library facilities. I’m told that with reflection and constexpr auto arg_reflections = std::vector{ reflexpr(args)... }; (constexpr vector is happening, yay!), I can emulate or do some of this. But I’m highly skeptical that going through a series of indirections with std::meta and reflexpr(args)... is going to give me a genuine boost to compilation times. If anything, I think it will make the problem worse. We already have variadic packs, we already have the notion that they may contain things and exist:

let us use them properly!

With the above snippet, I’m in control. Now I don’t need tuple. Or reflection. Or reflexpr. Or any of that. I get packs, I get to work with packs rather than treat each one like an ever-elusive, unobservable collection of maybe-Schrödinger’s cats. I don’t need to instantiate anything. I just let the compiler do the 1 operation people have been trying to propose since 2015; “get the element here from this pack”. Now, regular programming paradigms mean something. I do not need a special crash course in std::index_sequence or std::tuple or a hand-rolled type_list. I don’t need std::tuple_element_t: I’ll have decltype(). I don’t need std::get<T> or std::get<N>: I have language_func_to_get_pack_element...(i, args).

I don’t care what the actual name is: bikeshed it to death. static_pack_get has 0 hits for code on GitHub, maybe use that name as a raw language keyword. Whatever it’s called: this is the feature I need. This is what I was hoping for since C++14. And C++17. And C++20.

p1306 would be made even better if I could use a traditional for loop where I control the initializer and condition as well, without having to go through a constexpr version of std::ranges::iota. I sent an e-mail to the author of that paper, asking them to consider a traditional constexpr for loop with the typical expressions, just with the caveat that they must be compile-time ones. If that gets in, I don’t need to drag in std::ranges::iota just to get some indices, or std::tuple just to create a tuple of numbers.

This is the feature that is going to put the compilation times back in my hands and not in a library abstraction I don’t own. In perhaps hamster wheel levels of hilarity, when p0478 was rejected in 2015 the reason it was rejected was because they wanted someone to bring a paper forward for language_func_to_get_pack_element...(i, args). Papers like that were brought forward, and they died too. Do I dip my hands into the pot and try to write that paper again? Do I revive it, knowing that it was killed and abandoned?

Is that really a good use of my time…?

… Well?! Is it, Derpstorm?

I don’t really have the chops to tackle this stuff.

Any new papers now are beyond the C++20 cutoff. Unless it’s a pants-on-fire emergency, I doubt things can be proposed for C++20 solving this problem. I will bring a paper maybe in the C++23 timeframe after I talk to more people on the Committee: I really do not have time for back + forth in face to face meetings. I would rather meet offline to brew a good paper and just have the face to face meetings be voting on stuff and getting things done. I have already sent out at least 10 separate e-mails to people discussing various topics. (The current landscape for any of the above, plus my other papers, is looking grim honestly.) I have no idea how to convince any of them that this is useful: smarter, stronger, better human beings who came before me tried, and they failed. I won’t even have a Clang implementation of features until later: some people had one and still got rejected! I’m not a compiler engineer yet. Am I supposed to sincerely believe I will stand a better chance a mere 3, 4, or 5 years later? Am I supposed to think I can write a convincing paper for argument order that’d convince industry titans of its utilities? But, well,

this is what teamwork is for, right?

E-mails are trickling back in. I’m not the only one facing these problems. If you have had problems like these, go to either my future work repository to drop an issue; or, send me an e-mail or message so we can bikeshed this out. Some issues have already been filed. We might not make C++20, but C++23 is three years away. We have planning time. I might not have the chops,

but together, we do.

And while we wait for that to bake…

sol3’s compile times related to the above proposals will have to stay as they are. Thankfully, there’s a bunch more places where I can cull some significantly ugly tag-dispatch-and-SFINAE usage, and a few more places where I can cut out more tuples and function templates. I think I can squeeze another 10 minutes off the compile times of the project mentioned above at least, probably more if I get very dedicated. But this isn’t exactly a paid job, and I’ve done a fairly heroic amount of effort so far and school is starting in like 4 days…! Maybe I should switch to Jonathan Müller’s “productive week” model, focusing on weekends and stuff?

I was hoping to release sol3 this week, but I was not able to do documentation yet (and I refuse to make it the default branch without documentation). I need to improve these compile times. I need to do it. Even if I have to make all of my code horrible and ugly, it needs to be fast. It must be fast to compile…

… But, until that wonderful day?

Keep programming. See you soon! 💚