… Can I just not write this article, and we all pretend I wrote it and we all get it and we’re gonna move forward with great things so I don’t have to spend the mental cash to get this ball rolling? … No?

Fine, then. I’ll put down my money:

It was always possible to support the -fno-exceptions folk in Standards-Compliant C++ without any backwards compatibility breaks since C++11 and half of the gymnastics that we – as a pariah outside the blessing of the C++ Parametric Nondeterministic Abstract Machine and its Committee – employed to support ourselves have been so violently unnecessary it makes me want to puke a rainbow.

O’course, if you’re a regular here dearest reader, then you know that’s just my way of saying…

Mornin’!

Sleep well? :D

If you were following me on Twitter a long time ago (read: like 3 months ago in Non-Pandemic Time™), I was basically shit-posting about std::vector once a day while implementing the damn thing on my own, but with a few tweaks. Viewers of my stream would be privy to the details but we were able to prove that we could create an exception-less std::vector that passed the entirety of e.g. libstdc++’s vector tests and upheld the requirements of the standard library and had exactly equivalent performance of a std::vector. Because you are my most loyal and faithful reader, I am now going to reveal to you the dark arts required to make std::vector – and, consequently, every container and allocator-dependent portion of the Standard Library – purely noexcept.

Just below is a standards-conforming, weak, pathetic allocator that shivers in my grasps, awaiting what horrible things I will do to them:

template <typename T>

class alloc {

public:

using value_type = T;

T* allocate (std::size_t element_count);

void deallocate(T* first, std::size_t element_count);

};

And now, gaze upon this patch and TREMBLE at the transformative, enlightened force of our changes:

template <typename T>

class alloc {

public:

using value_type = T;

T* allocate (std::size_t element_count) noexcept; // (1)

void deallocate(T* first, std::size_t element_count) noexcept; // (2)

void validate_max(std::size_t element_count, std::size_t container_maximum) noexcept; // (3)

};

B E H O L D M Y P O W E R !

Haha Nice Shit Post !

Hahaha I wish !!

With two noexcept specifiers and one additional function call, you now have everything you need to turn every single container in the standard library into a purely noexcept one, dear reader. This includes the “sentinel node”-allocating implementation choices in certain unordered_map implementations, like MSVC’s, but also every other absolutely craven implementation choice someone might make. Yes, this is the 💦APEX💦LIBRARY💦DESIGN💦 we’ve all needed in our lives: conditional noexcept and an extra function.

Honestly, there isn’t even more to write here. This is literally the whole post. With two strategic keywords and one extra function, the entire standard library at all related to allocators, ever, can get used in (for example) the entirety of Windows:

“… if STL switched to making bugs [logic errors, domain errors] be contracts… and we could make

bad_allocfail fast, we could use the standard STL unmodified throughout Windows.” – Pavel Curtis, private communication

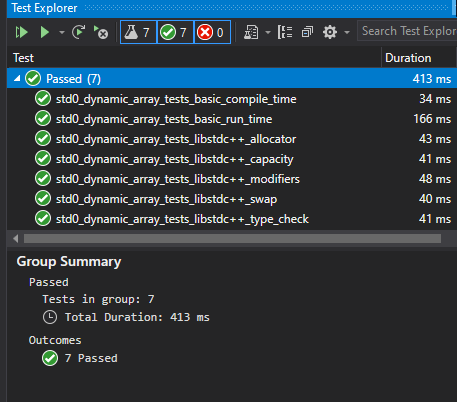

A million game developer projects, all of LLVM’s codebase, embedded projects throughout the globe… the possibilities are endless, which is why such a banal solution just floors me. I meme about apex library design but honestly there’s no way it can be this easy. It’s not like I could port the entirety of libstdc++’s test suite and several libc++ tests to use my std0::dynamic_array<T, Allocator> class and pass them all like it was no big deal–

Narrator: it is exactly that easy

I’m not even going to be pretend to be surprised: this is a (that is, this is one of the) logical conclusion of how to handle memory allocation errors. Most applications are simply not interested in dealing with the problem. Others yet still try to handle it (the exception version), but do it poorly. More disciplined and focused application writers (not library authors) attempt the second and third rows in this 13 year old table inside paper C++ paper from Paul Pedriana. Still, when it comes to “I can handle this on my own and I do not need to make every downstream user pay for it”, noexcept allocators are the best way to handle it.

So let’s make it so the user does not pay for it.

As demonstrated above, the cost of such freedom is a combination of 3 optional changes. The first is doing the obvious!

Make it noexcept

Can’t get rid of exception problems if the allocator tosses an exception! So, we do the obvious: don’t do it. There are several ways to do this, but here’s a bog-standard, basic implementation:

template <typename T>

T* alloc<T>::allocate (std::size_t element_count) noexcept {

// we will pretend alignment isn't

// a thing, for the moment

std::size_t byte_count = element_count * sizeof(T);

void* ptr = malloc(byte_count);

if (ptr == nullptr) {

// WHATEVER YOU WANT

std::terminate();

}

return static_cast<T*>(ptr);

}

We use std::terminate() here, but as Paul Pedriana’s EASTL paper (and many papers before – and after – his) note, there are multiple ways to handle allocation failure. Note that at no point can we let an invalid pointer escape the allocate function: this is not a chance to start returning nullptr from the function. (That is an ABI break and a contract break of what the Named Requirement Allocator means in the C++ Standard.)

There is also one slight adjustment to be made here: some compilers do not recognize malloc as a noexcept-like function, and upon seeing this code are tempted to vomit their own version of try { /* blah */ } catch (...) { std::terminate(); } in. This is mostly because compilers like Clang and GCC both mark their respective malloc “library builtins” as throw-capable (e.g., it is not marked with the string "fn" in its builtin definition). An internally-C++ implementation of malloc or free can indeed throw through the C boundary, however toxic and wrong many might consider that to be; no, it can’t be generally noexcept.

The fix to this is to basically force a noexcept-cast on the function. You, dear reader, can pick up Hana Dusíková’s handy utility to do that, or if you’re a hairy, jaded, dysphoric Neanderthal like me just cast and call:

template <typename T>

T* alloc<T>::allocate (std::size_t element_count) noexcept {

using f_ptr_ne = void*(*)(std::size_t) noexcept;

// we will pretend alignment isn't

// a thing, for the moment

std::size_t byte_count = element_count * sizeof(T);

f_ptr_ne c_alloc_call

= reinterpret_cast<f_ptr_ne>(malloc);

void* ptr = c_alloc_call(byte_count);

if (ptr == nullptr) {

// WHATEVER YOU WANT

std::terminate();

}

return static_cast<T*>(ptr);

}

Even if the C++ Standard explicitly sanctions these functions to be noexcept, we have to do this kind of work anyways to get perfectly consistent code generation across platforms. But, once we do the work we now have the general blueprint for a noexcept-based allocate function. The exact same process can be done for the deallocate function, so we’re not going to write the definition out here to see, dear reader. (Is this where, in the math books, they would say “Exercise left to the reader” …?)

Still, there is more to be done!

Purging the other exception: length_error

validate_max is our escape hatch here. The only reason this is necessary for std::vector – and every other container – is because in the Standard Library we do this thing where we force a contract violation-handling scheme with exceptions. Take a look at the description for reserve(size_type n) from std::vector:

Throws:

length_errorifn>max_size().227

std::length_error is a std::exception-derived type that gets deliberately and unavoidably thrown if we violate what the max_size() of the container is. Note that it is the max_size() of the container, and NOT the allocator (though, the two can be related to one another). This serves two purposes for the library.

The first is obvious: diagnosing a precondition violation like this with an exception is not just a matter of taste, but of security and safety. Too-large values can manifest generally as overflow-to-too-small-value bugs, which result in indexing out of bounds and inviting security vulnerabilities on top of general memory corruption.

It also serves another purpose, separate from the max_size() function found on allocators: only containers themselves know whatever special invariants they need to maintain their behavior.

[[segue("begin")]] For example, std::vector – in the general case – must maintain that there is at least (allocator::max_size() / 2) - 1 space always available, because a push_back can trigger a resizing operation. resize needs to be able to hold the old memory in place, before copying it to the new location plus whatever additional items were added and then destroying the old memory. This means that allocator::max_size() is not the “final” determination of how big your container can be, but the implementation strategy of the container itself. This is why containers have their own max_size() function. Other containers might have fixed overhead: for example, a std::list may do (allocator::max_size() * sizeof(value_type)) / sizeof(_M_internal_node) to account for how many nodes it can possibly allocate for the given value_type of the std::list. It is also subject to the constraints of the difference_type, which is – generally speaking – a numeric value capable of representing signed or unsigned distances between two pointer types.

This ultimately means that, given current architecture, one could never have a std::vector that contains more than half of your given memory inside of itself since maximum_pointer_value - minimum_pointer_value cannot exceed difference_type’s representative abilities. This is not what is done in practice, however, on 64-bit-memory 32-bit-pointers-and-integers machines: it’s more than common to index all 4 GB, so long as the difference is never taken between two pointers / iterators it’s generally all chummy. (Note that this is nearly impossible with most standard implementations, since .size() is calculated as return end() - begin();) (Please don’t do this and just build your software under normal conditions 🥺!!) [[segue("end")]]

Forays into the motivation of max_size() put away, now all the container has to do – when preparing to resize – is detect that validate_max(element_count, my_container_max_size) is a real function that exists on the allocator. The default implementation (taken care of by allocator traits) would be similar to…

namespace std {

template <typename _Alloc>

static void allocator_traits<_Alloc>::validate_max([[maybe_unused]] _Alloc& __alloc,

size_t __element_count, size_t __container_max)

{

if constexpr (requires { __alloc.validate_max(__element_count, __container_max ); }) {

__alloc.validate_max(__element_count, __container_max);

}

else {

if (__element_count > __container_max)

throw length_error("no :3");

}

}

}

but as an opt-in, optional function on our allocator we can define it as:

template <typename T>

void alloc<T>::validate_max(std::size_t element_count, std::size_t container_max) noexcept {

if (element_count > container_max)

std::terminate(); // no :3

}

Of course, this is our “default” implementation, but you can do other things: log an error and crash, call a function which hits a debug break, or even do nothing and commit the cardinal sin of undefined behavior with all the nasal demons it implies. It’s your choice: the implementation does not do this on your behalf, and you get to choose how to handle it when you care.

And That’s It

Yes. It is up to the implementation to thoroughly noexcept-proof their code, but an examination of containers such as unordered_map and vector in the VC++ STL, libstdc++, and libc++ all reveal that these changes essentially enable the entire container to be made noexcept-safe. The only prominent exception (hah!) is the container.at(...) function, which I personally believe should be deprecated and blown up out of our container types and instead replaced with a at(container, ...) free function instead that I do not have to put in my code or think about if I so choose!

Of course, this is about backwards-compatible fixes: can’t go deprecating or destroying functions in freestanding implementations (yet). Implementers will have to do whatever the hell they’ve always done to handle .at() failures in their freestanding implementations and the rest of us can use literally every other function on vector, confident that there are no sudden or surprising exit paths out of our functions and that we can handle all failures the way we need to, not the way the standard library thinks we should.

But what this does mean is that we CAN escape the tyranny of whatever the implementers feel like is a good idea for their platform, at the cost of our use cases.

For example, the MSVC STL uses a special sentinel node allocated in its unordered_bäa containers: this means that not only are their default constructors not noexcept, but their move assignments / move constructors are not either. This means that if you, say, put an associative std::unordered_map<std::string, ShaderParameter> inside of Shader class, and you have a std::vector<Shader> somewhere, modifying that vector does not actually trigger element moves inside if it resizes ever. It copies. Every shader and its contents? Copied. Every parameter in that map? Copied. Had some uniform buffer location information? Copied. One by one by one, because you let the “default” implementations the compiler generated – and correctly deduced were not noexcept – fly.

This is why game developers, embedded developers, high-performance server developers, and more are wary of the standard libraries given to them. For something that is seen as “Quality of Implementation”, the performance degradations can be the difference between lightning fast pointer swaps or utterly damaging copies, giving Howard Hinnant’s move semantics a swift elbow drop of implementer reality. When can MSVC change this? When they feel like it, when they decide it’s worth it to break the ABI, when they decide it’s good for their customers. You have no control; you have surrendered it to the implementation.

And the implementation does not like your use case.

At the Precipice

Exceptions – alongside RTTI – continue to be the feature that you pay for, even if you don’t want it and can do better for your domain space. We strongly tied exceptions to one of the most fundamental operations in our programming language – retrieving memory – and made it nearly impossible to separate the two in regular code. This cuts out many industries from Standard C++. As Ben Craig so thoroughly explains in his paper P1105 with Ben Saks called “Leaving no room for a lower-level language”:

Kernel and embedded environments can’t universally afford exceptions. Throwing an exception requires a heap allocation on the Itanium ABI, and a large stack allocation on the Microsoft ABI, neither of which are suitable in kernel and embedded environments.

…

Even when exceptions aren’t thrown, there is a large space cost. Table based exception costs grow roughly in proportion to the size and complexity of the program, and not in the number of throw sites, catch sites, or frames traversed in an exception throw. Since table based exception costs grows with program size, rather than how much it is used, it is not zero overhead.

We exist in a world where we have cut our ecosystem in half, and there is no C compatibility or other boogeyfolk to blame. We did this one all by ourselves, and have continued to make it worse and worse in both language and library over the decades. We are letting a large majority of our developers down with a C++ that does not serve their needs and continuing to polarize them by not offering any solutions. Meanwhile, C, Rust, Zig and other languages – at the very least – do not pretend to support these folks with the promise of portability and compatibility while swinging an axe at their Achilles heel.

C++98 exceptions came before noexcept. Even if we had a throw() specifier, we barely did anything meaningful with it. C++11 gave us move semantics and the noexcept that allowed us to think further and farther beyond, dear reader! But, the weight of C++98’s inheritance-based exceptions are already here to stay, and they are bound to our allocation model.

Changing the way the default allocator behaves breaks everything; this is why Herb Sutter’s suggestions in P0709, Revision 3 failed in the 2019 Köln (Cologne), Germany meeting, and will consistently fail:

The default

std::allocatorand non-placement globaloperator newshould terminate on failure. No effect onnew(nothrow)which will continue to report null on failure: 0-17-6-10-5 (SF-F-N-WA-SA).

Backwards compatibility is King in C++, which means P0709’s sentiment to just “make it non-throwing and terminate all the time instead” is wrong for the C++ ecosystem.

To understand why, we need to look at something I like to call…

The Chandler Principle

It is a timeless adage that can be summed up best by Chandler’s own words:

C++ doesn’t give you performance; it helps you control it.

– CppCon 2014: Efficiency with Algorithms, Performance with Data Structures

The C++ Standard Library, as it stands today, does not help you control performance when it comes to RTTI and Exceptions. It gives you a juicy, unchangeable set of things and there are no knobs to twist. P0709, Revision 3 (not the latest) failed miserably in this regard: it just swapped one bad default out for another default which is equally offensive.

So, let’s follow the principle: let’s give users control.

Following the Chandler Principle, Properly

The way to follow the Chandler principle is what the current P0709 now terms an exploration of “opt-in allocator compatibility”. It does not go into details about it, which is exactly why I had to do the implementation myself and come up with the design. This is why the approach described here, dear reader, is the maximally effective design. Notably:

- we let users introduce their own non-throwing allocators, which change the type of every container they’re injected in (this prevents both API and ABI breaks and accidental conversions between the two); and

- we respect your

noexceptqualifiers and adapt the code based on such by letting librarians use conditionalnoexcept, while letting them continue to have whatever defaults they currently put up with for the current allocator.

The image of passing libstdc++’s and some of libc++’s tests above is critical: we do not break old code with these changes. std::length_error is still thrown – and caught – by using the old std::allocator in these tests. But, when the new, non-throwing std0::allocator is used instead, we get the guarantee (checking static_assert and running the tests) that we do provoke a customized failure handled by the validate_max function.

This is a marked improvement over how this is currently handled in “kernel mode” builds on MSVC or -ffreestanding builds in libc++ or libstdc++. What implementations tend to do is just expand some violation-handler macro which almost certainly just leads to an abort/terminate, or it just outright bans that code in general. It is not “yours to control” in any standard fashion, and you are always needing to beg your implementers for extensions; crumbs, always swept off the master’s table and onto the floor.

No More Crumbs

With these changes (and perhaps some others made to certain allocating algorithms), it means that free standing can provide their own allocators to the standard library. It means they can have the control and confidence they need for their code bases, without having to roll and entirely new standard library all over again. And with some additional changes that were marked tentatively ready for Core Working Group on Wednesday, August 19th, we are getting closer to where we should’ve been a long time ago.

Sure, there’s room for allowing for a new kind of Allocator that can return nullptr to indicate failure, and building a new vector type with maybe_push_back that returns a std::expected/stx::Result or similar. But that is another layer, another library.

This is for the standard library. The library that everyone should be writing against and improving, not forking and running off into the dark with special modifications they can never bring back to the light of day. Everyone should be able to have an allocator that does not throw, and containers that do not force exceptions. It is not “just for Freestanding”. We cannot continue to fail our userbase with hard lines and forced defaults. For too long we treated “weird devices” like second-class citizens, inviting them to the So-called Great C++ House but leaving them to sleep on the floor in the foyer and to cling to the ankles of the Hosted Master. We expect them to be “grateful” for the things we do better than C, while dismissing their use cases out-of-hand as too hard or too radical to address properly.

This is not some herculean and monumentally difficult task. Embedded devices are not complete sorcery. This is not hard. It is not difficult. A professional standard library developer estimated a standard compliant vector developed in 6 weeks “would be impressive”; I did it in 2 weeks while streaming the entire process live until my computer exploded. I wrote my own allocator_traits, my own uninitialized_foo algorithms with allocators, discovered a few MSVC bugs, backtracked my allocator_traits to not use concepts anymore from said bugs, explained every design decision, tested it, and performance tuned it live in front of anyone who would stop by the stream.

But the largest companies on earth backing the biggest standard libraries and sending the most individuals to every Committee Meeting could not solve this problem?

We can do better; we can have an entirely noexcept std::vectors, std::unordered_maps, std::lists and more. The C++ standard library does not just belong to the big companies and their dedicated teams and the hosted implementations on big servers. It is for us too, the small studios and the tiny systems-on-a-chip and the handheld devices. When we take care of freestanding, we take care of everyone; their use case is just as good as my use case. I will fight alongside Ben Craig. I will follow the Chandler Principle. No longer will I kneel, licking the crumbs off from the table.

I am freestanding.

And I hope you are too, dear reader.

Until next time. 💚